For two years, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation has failed to deliver a winner. Is it because relative good leadership is so rare in Africa or is the impasse a product of a different agenda?

As reported by the BBC: "Many leaders of sub-Saharan African countries come from poor backgrounds and are tempted to hang on to power for fear that poverty is what awaits them when they give up the levers of power.”

And with that rationale, the award was started in 2006; indeed, for the very good reason of remedying the curse of prolonged leadership in Africa and to re-brand Africa less in the image of the Mugabes, the Abachas and the Idi Amins.

The prize offers a generous reward: “$5m (£3.1m) to former leaders who have promoted good governance, with $200,000 (£123,000) per year for the rest of their lives,” according to the BBC.

Since its foundation, two leaders have benefited from the award; Botswana's former President Festus Mogae and Joaquim Chissano, Mozambique's former president, both after two successful terms in Office.

In 2009, Ghana’s John Kufuor, South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki, and Nigeria's Olusegun Obasanjo, after leaving office, qualified for that year's prize consideration.

John Kufuor and Obasanjo had two successful full terms. Thabo Mbeki, however, was forced out of office short of his full two terms. There has since been question about his inclusion in the qualification process.

However, one is compelled to wonder what was forcefully different from the presidency of John Kufuor who failed to receive the award and Mogae or Chissano who received the award.

If the message was to encourage presidents “from poor backgrounds” who would otherwise be tempted “to hang on to power for fear that poverty is what awaits them when they give up the levers of power,” then the consequence of failure to give the award to either Kufuor or Obasanjo should be considered.

After all, this impasse has its own converse message: Were they not good enough?

At this point, the intent of the award becomes confusing; What interest does it serve to tell the world that Africa has not been able to produce a good leader for two consecutive years?

Is it still to improve leadership on the continent or more so to increase the influence of Mo Ibrahim within the global community?

In 1998, Mo Ibrahim founded Celtel, a tele-communications company which he sold in 2005 to MTC of Kuwait for $3.4bn, the most lucrative business transaction ever in Africa.

Is the prize then a stunt to improve more business chances for him on the continent?

Some may not understand how publicity stunts work. Sir Richard Branson can embark on high risk adventures in floating balloons and still promote the fortunes of Virgin, his company.

Mo Ibrahim, not toying with his life but with good intent in mind, can increase his business chances in the same manner.

However, and as observed so far, rewards from his foundation have not been constant for Africa or the nominees, at least for two years.

Kufuor, Obasanjo and Mbeki as leaders were good and even excellent; in relative terms, far better than the majority preceding them.

But the award is Mo Ibrahim’s to give, the reputation for good governance is Africa’s to keep, burnish or lose and the joy the recipient’s to receive.

Seen in the above light, withholding the award for two years does more damage to the continent’s image than the good the intended re-branding could have accomplished during the same time period.

The withholding casts aspersion on Africa in the sense that for two years she has not been able to produce a single, relative, worthy leader; a notion that also prompts a chuckle and a resulting image at the same time of the same old hag that can't produce quality leaders.

But, pity the three leaders (Obasanjo, Mbeki, Kufuor) first. They probably did their best under the circumstances. However, they would have to endure the humiliation. They have been found wanting by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

Meanwhile, the Foundation's reputation does not suffer. Its inability to produce a leader is no problem. It's Africa's fault.

The perception of the Foundation's benevolence remains positive even though she did not spend a penny on the prize for two years.

And the search for the next good leader, who apparently will be hard to find, continues, but for how long?

The Mo foundation will not say why Obassanjo, Kufuor, and Mbeki were not good enough. A statement on why can help future aspirants.

The statement is needed, considering Mo Ibrahim’s own words for re-rebranding Africa:

"Two or three terrible tyrants,” may exist in 53 countries in Africa, but “Corruption exists everywhere. … We have to have a balanced view of governance," he said to the BBC in October 2009.

The implication is we should seek to improve quality leadership in Africa gradually.

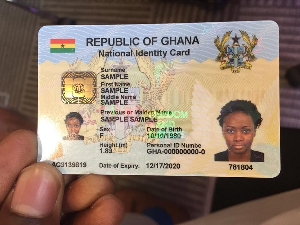

Presidents in Africa are super-powerful when in office. Once out, their power diminishes exponentially. Hostile successors would make sure to limit their power and influence. The process is called PHD (the pull him down syndrome).

Withholding the award from a nominee just out of office, could be seen as a concession to a successor regime that may be hostile to the idea for partisan reasons.

However, the message that “The world's most valuable individual prize is not being awarded for a second year because no-one is deemed worthy” is one that gives the continent a black eye; more so because it resonates.

It highlights the paucity of good leadership in Africa. To prevent more damage, there ought to be a different approach now; a different philosophy if you will, for awarding the prize.

This new approach should require the broadening of good presidential samples on the continent. Instead of some abstracts, consider the qualification for the award in relative terms.

Grant it to the best in the bunch and allow future competition to do the clean up.

In this sense, there will always be a winner each year, even if it means reducing the size of the prize in accordance to merit; while allowing simultaneously miscreants on the leadership scene to covet and envy the winners of the prestigious prize, year in and year out.