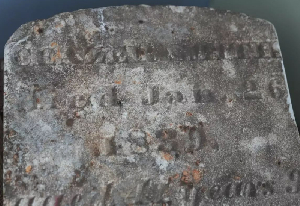

A tombstone dated 1839 is displayed at the recently rediscovered burial ground in New York

A tombstone dated 1839 is displayed at the recently rediscovered burial ground in New York

College students in upstate New York are digging through backyard dirt as part of an archaeological project that could unlock the lives of African Americans buried there centuries ago.

The site, nestled in a residential neighborhood in Kingston, was once a cemetery for people enslaved as far back as 1750. It remained a burial ground until the late 1800s, when urban growth covered the site. Now, students are carefully excavating the land, uncovering remnants of history.

Over the past 3 summers, the remains of up to 27 individuals have been unearthed. Grave markers were found, including one for Caezar Smith, born into slavery and freed before his death in 1839. Researchers hope tests on the remains could reveal details about those buried there and possibly identify living descendants.

“The hardships of those buried here cannot go down in vain,” said Tyrone Wilson, founder of Harambee Kingston, the nonprofit working to restore the burial ground. The group aims to turn the site, known as the Pine Street African Burial Ground, into a respectful resting place. “We have a responsibility to fix that disrespect.”

The site is one of many forgotten African American cemeteries across the U.S. gaining renewed attention. In Kingston, advocates purchased a property covering part of the old cemetery and now use the house as a visitor center.

The half-acre site was designated as a cemetery in 1750, but burials may have begun earlier and continued through 1878—more than 50 years after New York abolished slavery. Researchers found that individuals were buried with their feet facing east, symbolically preparing for resurrection at sunrise.

At the Harambee property, remains are covered in patterned African cloth and left undisturbed. However, remains found on neighboring land are exhumed and reburied at Harambee.

Students from the State University of New York at New Paltz recently completed their third summer of supervised excavations. While the work earns academic credit, anthropology major Maddy Thomas said the project goes beyond academics. “I don’t like when people feel upset or forgotten. And that’s what’s happened here. So we’ve got to fix it,” she said.

Harambee is raising $1 million to transform the site into a formal memorial honoring the African heritage of those buried there. Plans include a tall marker to commemorate the mostly unmarked graves.

The only intact headstone found so far is for Smith, who died at 41. Historical research has identified others potentially buried there, including a man named Sam and a 16-year-old girl, Deyon, hanged in 1803 for allegedly killing the daughter of her enslavers.

The cemetery was obscured by a lumberyard in 1880, despite some gravestones still standing. In 1990, archaeologist Joseph Diamond discovered the cemetery’s location from an 1870 map while conducting a city survey. Around the same time, building owner Andrew Kirschner unearthed bone fragments while digging for a sewer pipe, leading to the cemetery’s rediscovery. Though its existence was known, advocates didn’t secure the property until 2019, despite earlier plans to develop the site into a parking lot.

Similar stories of neglect and rediscovery have emerged nationwide. Manhattan’s African Burial Ground National Monument, resting place of an estimated 15,000 free and enslaved Africans, was unearthed in 1991 during construction. In nearby Newburgh, a 2008 renovation project uncovered more than 100 sets of remains beneath a former school.

Antoinette Jackson, founder of The Black Cemetery Network, noted that many of the 169 sites listed in their archive had been destroyed or built over. “A good deal of them represent sites that have been built over—by parking lots, schools, stadiums, highways,” she said.

With limited historical records in Kingston, advocates hope tests on the remains will fill in gaps. DNA and isotopic analyses may shed light on where individuals came from and connect them to living descendants. Wilson emphasized the importance of uncovering these stories. “One of the biggest issues we have in African culture is that we don’t know our history,” he said. “We don’t have a lot of information about who we are.”