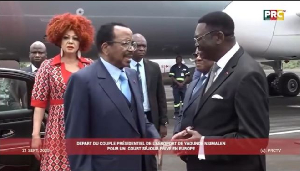

Paul Biya and wife leaving for Switzerland, September 21, 2025

Paul Biya and wife leaving for Switzerland, September 21, 2025

For the first time, the opposition parties in Cameroon have come “close” to unseating 92-year-old Paul Biya, who has run the country since 1982.

The stiffest competition for Biya in the 2025 election came from 76-year-old Tchiroma Bakary, a former ally and government spokesperson, who contested on the platform of the Cameroon National Salvation Front.

He won more than 35% of the vote – the second highest ever scored by an opposition candidate since Biya has been contesting.

Though it was one of the best performances by opposition parties in Cameroon since 1992, the opposition suffered from its failure to present a united front and field a single candidate.

Biya once again triumphed, albeit with a reduced majority of 53.66%. Other candidates scored a combined 11%.

His previous win in 2018 was at 71.28% against Maurice Kamto’s 14.23%.

This result is at variance with Bakary claiming an overwhelming victory at the polls with 60%.

His claims have been dismissed by the constitutional court and the electoral commission.

Biya’s controversial win has resulted in countrywide protests and a crackdown, resulting in casualties.

I am a longtime scholar of and political commentator on African politics, regime types, and democratic governance, with a keen interest in Cameroon.

I argue that Cameroon is at an inflection point, where Biya’s triumph might herald a “quiet” resignation to see through one of the world’s longest presidencies.

For Biya, the to-do list couldn’t have gotten any longer.

For Cameroon and the continent, democracy is yet again being asked hard questions with no obvious answers.

Divided opposition

Determined by a simple majority, the election meant that Biya – sometimes described as the absent landlord due to his prolonged stay outside Cameroon – only needed a sliver of support to triumph for a life term presidency.

His new seven-year term of office ends in 2032, by which time he will be close to 100 years old.

Though his share of the vote fell by about 20 percentage points, he triumphed again because of the perennial challenges faced by the opposition.

Failure to coalesce around a single unifying candidate meant that the opposition, with 11 candidates, was still seen as divided.

With all state apparatus, especially the constitutional court, stacked against the opposition, it was not surprising that they were fighting a losing battle from the start.

The challenges ahead are monumental.

With dissatisfaction running high, one of the core priorities is to ensure the political stability of his regime.

Recent forced regime changes iWestst Africa, and very recently in Madagascar, would perhaps give pause for thought about the vulnerability of the regime.

It is possible that sustained political upheaval could provoke a palace coup, as Gabon attests.

That said, Biya’s effort to coup-proof his regime with loyalist military co-ethnics, the Betis, appears to have bought him some comfort.

Many of the senior officers’ fates would be intertwined with Biya’s.

The reality that his reported triumph comes with a much-reduced mandate would mean reasserting legitimacy will be another priority. Biya will have to work to establish or “enforce” his legitimacy both domestically and internationally.

The South West continues to be a place of concern.

With the Anglophone crisis – caused by perceived marginalisation of the Anglophone south-west – still festering, the election result may galvanise the rebellion in the hope that renewed active hostilities may create conditions for willingness to settle the conflict before Biya bows out.

There is no question that Biya has entered into the last mile of his life presidency.

The political elite jostling for post-Biya relevance will inevitably become more pronounced.

This infighting could destabilise the regime and make it a challenge to hold course.

Ambitious elites may abandon Biya’s ship, as Bakary did.

On the campaign trail, Biya promised especially the young Cameroonians and women that their “best is yet to come”.

He was acutely aware of the high level of dissatisfaction, and his regime will be pressed to address their plight.

According to the World Bank, about 40% of Cameroonians live below the poverty line.

Urban unemployment is running at 35% and many educated youths face challenges in obtaining formal employment.

A 2024 Afrobarometer survey says 51% of young Cameroonians have considered emigrating.

The perennial challenges of systemic corruption, service delivery, poverty, nd slow growth persist.

Today, the average Cameroonian is wealthier than in 1986. How Biya’s new term attends to this will be crucial to temporarily assuaging pent-up frustration.

As the 92-year-old Biya begins another term of office, along with the president of the constitutional court, Clement Atangana (84), chief of staff Claude Meka (86), president of the senate Marcel Niat (9), and national assembly speaker Cavaye Yegue (85), Cameroon should confidently be looking at a generational shift after the Biya era.