Belgium human zoos - Photo credit: RMCA Tervuren

Belgium human zoos - Photo credit: RMCA Tervuren

The mistreatment of Africans in Belgium’s “human zoos” has been brought to light by a historian. In these degrading exhibits, people were treated like animals by cruel and racist handlers.

Guido Gryseels, former director of the Africa Museum—where King Leopold II once opened one such exhibit—told The Sun that Belgium still needs to reckon with its brutal colonial history.

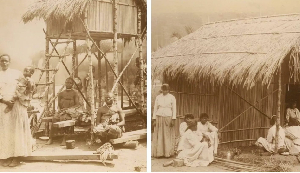

Disturbing images show Congolese men, women, and children displayed in mock villages, ogled by tourists and locals from behind bamboo fences.

In 1958, Belgium showcased its post-war social, cultural, and technological advancements through a world fair. One exhibit featured a live display of Congolese people in a fabricated village.

Photographs of men, women, and children standing near straw huts in so-called “traditional” attire, in an inhumane and demeaning setting, have surfaced. In one particularly shocking image, a little girl stands in a pen, while visitors gawk through a bamboo fence and someone offers her food. Onlookers laughed, heckled, and reportedly even threw bananas at the villagers.

Unveiling Belgium’s dark past: The shameful ‘Human Zoo’ of King Leopold II’s colonial era

This exhibit, believed to be the world’s last human zoo, took place just 66 years ago.

Prior to the 1958 world fair, King Leopold II ordered a similarly cruel human zoo to be staged in 1897 on the grounds of what is now the Africa Museum. A fake village was erected, leading to the deaths of seven Congolese people due to harsh conditions.

Gryseels, who still serves on the museum’s board, said the museum has since confronted its colonial past and undergone significant changes. Reflecting on the 1958 human zoo, which was separate from the Africa Museum, Gryseels said: “The Congolese staff felt very humiliated because people were throwing bananas and treating them as though they were wild animals. Many of them left, resigned, and returned to Congo.”

He added: “It was a propaganda tool filled with stereotypes, portraying Africans as uncivilized and promoting the false narrative that Belgium brought ‘civilization’ to Congo.”

Belgium and Congo’s Colonial History

The Democratic Republic of Congo was under Belgian rule from 1908 to 1960, but the exploitation began earlier. In 1885, King Leopold II seized control of Congo, establishing an infamously violent regime responsible for millions of deaths. Some estimates suggest around 10 million Africans were killed during his reign, though the exact figure is disputed by historians.

Congolese people were forcibly brought to Belgium and displayed in these fake villages or “human zoos.” According to Britannica, Belgium’s colonial policy was based on “paternalism,” treating Africans as if they were children in need of guidance and control.

King Leopold II, who died in 1909, is remembered for his brutal colonization of Congo. However, after World War I, statues of him were erected to bolster national pride, whitewashing the atrocities committed under his rule. This dark history went largely unacknowledged until the 21st century.

The Africa Museum, once a tool of colonial propaganda, has evolved into a space that confronts this painful past. Gryseels explained: “King Leopold II opened the museum as a propaganda instrument and brought 236 Congolese people to Belgium to set up villages near the museum.”

In 1897, during one of the museum’s human zoos, some Congolese participants tragically died from pneumonia and influenza after being forced to stand in the cold, exposed to gawking visitors.

Compiled by Henry Holloway, here are key points about King Leopold II:

Leopold II ruled Belgium from 1865 to 1909 and was the longest-reigning monarch in its history. His legacy, however, is stained by the atrocities committed during his personal colonial project in the Congo, where his regime exploited the region’s resources—especially rubber and ivory—amassing vast wealth while subjecting the local population to forced labor, savage punishments, and widespread abuse.

Millions perished under his reign of terror. Outrage over the abuses eventually led to international condemnation, forcing Leopold to relinquish control of the Congo Free State a year before his death in 1909.

Gryseels noted that human zoos were common across Europe, Asia, and America at the time. “About a million people visited the 1897 human zoo,” he said.

He expressed pride in his efforts to transform the museum from a colonial institution into one that exposes the grim realities of Belgium’s past. Gryseels believes the museum now plays a key role in the fight against racism. “When I became director, about 95% of Belgians still believed that colonialism was a good thing for Congo. Now, recent research shows less than a quarter of the population holds that view.”

Gryseels concluded by saying the museum’s transformation is helping to “decolonize minds in Belgium” and that it now highlights the rich cultures of Africa while also explaining the moral wrongs of colonialism.