US dey give automatic citizenship to anyone dem born for di kontri, but dis principle no be di norm

US dey give automatic citizenship to anyone dem born for di kontri, but dis principle no be di norm

President Donald Trump executive order to end birthright citizenship for America don spark several legal challenges and some anxiety among immigrant families.

For nearly 160 years, di 14th Amendment of di US Constitution bin establish di principle say any body wey dem born for di kontri automatically na US citizen.

But as part of im crackdown on migrant numbers, Trump wan deny citizenship to children of migrants wey either dey di kontri illegally or on temporary visas.

Di move wey be like say get public backing. One poll wey Emerson College carry out suggest say many Americans wey support Trump pass those wey dey against am on top dis mata.

But how dis one take compare to citizenship laws around di world?

Wetin be birthright citizenship?

Birthright citizenship na one legal principle wey give automatic citizenship to anyone dem born within a kontri borders, e no mata di parent nationality or immigration status.

Dem dey grant am under di principle of jus soli, wey mean right of di soil.

Birthright citizenship worldwide

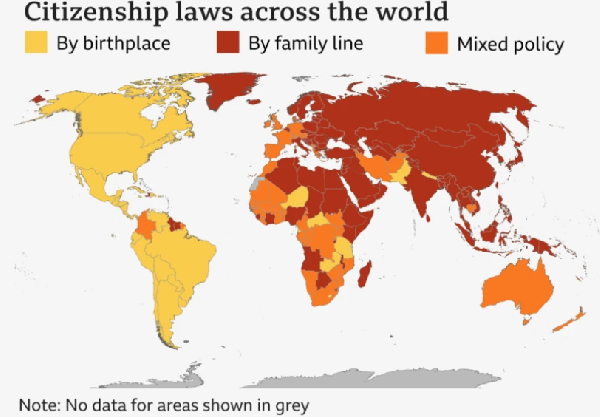

Birthright citizenship, or jus soli (right of di soil), no be di standard globally.

US na one of about 30 kontris - mostly for di Americas - wey dey grant automatic citizenship to anybody dem born within dia borders.

These kontris according to World Population Review and CIA World Factbook include:

. US

. Canada

. Mexico

. Argentina

. Brazil

. Guatemala

. Brazil

. Peru

. Bolivia

. Honduras

. Venezuela

. Ecuador

. Chile

. Paraguay

. Urugua

. Nicaragua

. Costa Rica

.Panama

.Guyana, and among odas

Dis dey different to di principle wey many kontris for Asia, Europe, and parts of Africa dey follow. These kontri dey follow di jus sanguinis (right of blood) principle, wia children inherit dia nationality from dia parents, regardless of dia birthplace.

These kontris include:

.Nigeria

.Angola

.DRC

.South Africa

.China

.Russia

.Ukraine

.Germany

.France

.Saudi Arabia

.Chad

.Australia

.India

.Ghana

.Libya

.Turkey

.Egypt

.Australia

.South Africa

.Greenland, and among odas.

Oda kontris get combination of both principles, dem also dey grant citizenship to children of permanent residents.

John Skrentny, one sociology professor for di University of California, San Diego, believe say, although birthright citizenship or jus soli dey common throughout di Americas, "each nation-state get im own unique way dem dey do am".

"For example, some involve slaves and former slaves, some no get. History dey complex," e tok. For US, goment adopt di14th Amendment to address di legal status of freed slaves.

However, Oga Skrentny argue say wetin almost all of dem bin get in common na "building a nation-state from a former colony".

"Dem gatz dey strategic about who to include and who to exclude, and how to make di nation-state governable," e explain. "For many, birthright citizenship, wey dey based on being born for di territory, to build dia state.

"For some, e encourage immigration from Europe; for odas, e ensure say indigenous populations and former slaves, and dia children, go dey included as full members, make dem no dey stateless. Na particular strategy for a particular time, and dat time fit don pass."

Shifting policies and growing restrictions

In recent years, several kontris don revise dia citizenship laws, tighten or cancel birthright citizenship sake of woory on top immigration, national identity, and so-called "birth tourism" wia pipo go visit one kontri just to born dia baby for there.

India, for example, one time dey grant automatic citizenship to anybody dem born for dia soil. But ova time, concerns ova illegal immigration, particularly from Bangladesh, bin lead to restrictions.

Since December 2004, any pikin dem born for India na only citizen if both parents be Indian, or if one parent na citizen and di oda parent no dey considered as illegal migrant.

Many African nations, wey historically follow jus soli under colonial-era legal systems, later abandon am afta dem gain independence. Today, most African kontris require at least one parent to be citizen or a permanent resident.

Citizenship even dey more restrictive for most Asian kontris, where primarily na by descent, as e dey happun for nations like China, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Europe don also see significant changes. Ireland na di last kontri for di region to allow unrestricted jus soli.

Dem cancel di policy afta one June 2004 poll, wen 79% of voters approve a constitutional amendment wey require at least one parent to be citizen, permanent resident, or legal temporary resident.

Goment say change bin dey important becos foreign women dey travel come Ireland just to born in order to get EU passport for dia babies.

One of di most severe changes bin happun for di Dominican Republic, wia, for 2010, dem do one constitutional amendment wey redefine citizenship to exclude children of undocumented migrants.

One 2013 Supreme Court ruling bin strip tens of thousands - mostly of Haitian descent - of dia Dominican nationality. Rights groups bin warn say dis fit leave many stateless, as dem no get Haitian papers too.

Many international humanitarian organisations and di Inter-American Court of Human Rights bin condemn di move.

Sake of public outcry, di Dominican Republic pass one law for 2014 wey establish one system to grant citizenship to Dominican-born children of immigrants, particularly favouring those of Haitian descent.

Oga Skrentny see di changes as part of one broader global trend. "Now we dey for era of mass migration and easy transportation, even across oceans. Now, individuals also fit dey strategic about citizenship. Dat na why we dey see dis debate for US now."

Legal challenges

Within hours of President Trump order, Democratic-run states and cities, civil rights groups and individuals bin launce various lawsuits.

Two federal judges don side wit di plaintiffs, most recently District Judge Deborah Boardman for Maryland.

She bin side wit five pregnant women wey argue say denying dia children citizenship violate di US Constitution.

Most legal scholars agree say President Trump no fit end birthright citizenship wit executive order.

Na courts go later decide dis mata, Saikrishna Prakash, one constitutional expert and University of Virginia Law School professor, tok. "Dis no be sometin e fit decide on im own."

Di order now dey on hold as di case make am through di courts.

E neva dey clear how di Supreme Court, wia conservative justices form supermajority, go interpret di 14th Amendment if di mata later reach dia table.

Trump justice department don argue say di citizenship issue only apply to permanent residents. Diplomats, for example, be exception.

But oda counter say oda US laws apply to undocumented migrants so di 14th Amendment suppose apply too.