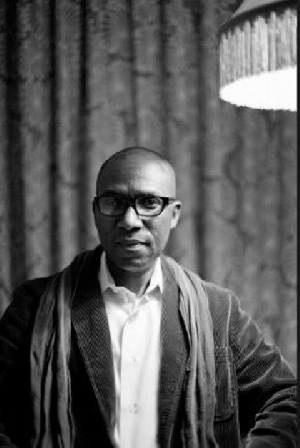

Mohammed Naseehu Ali is a Ghanaian-American writer

Mohammed Naseehu Ali is a Ghanaian-American writer

Several Ghanaians have travelled to various countries for one reason or the other. Some succeeded, others who were less fortunate did not, owing to several factors.

Ghanaian-American writer Mohammed Naseehu Ali is one of such persons, born a Ghanaian in Kumasi in a predominantly Islamic neighbourhood called Zongo, Mohammed, moved to NewYork in America to continue his education and build a life.

In this piece, he tells his story of how for years, he had to face seemingly endless challenges in the bid to satisfy his dream of becoming an American citizen.

The long unfinished path to becoming an American citizen

Like most young artists, I was full of pompous idealism when I moved to New York City, in the summer of 1995. I had just graduated from Bennington College, and I was in the process of falling in love with American culture and people, especially the artistic community I discovered in Brooklyn.

Yet I was also repulsed by the idea of becoming an American citizen, which in my mind was tantamount to a selling-out of sorts, and also a sign of disloyalty to my tribe and my country of origin, Ghana. I was beleaguered by the fear that, once I became a naturalized citizen, I would lose the artistic voice and moral integrity to represent my people, to tell their stories as I do in my fictional work.

So, with a job that guaranteed me an H1-B work visa for the next six years, I foolhardily ignored the implorations of African friends in the Bronx, and disregarded the cardinal rule of the immigrant in the United States: Seek ye first the green card, and everything else shall follow. I was too busy enjoying being American to care about what anyone thought, and still young enough to feel invincible. I sneered at the idea of a green-card marriage, and flatly refused to falsify documents and take advantage, as many Africans did, of the refugee status given to Liberian and Sierra Leonean citizens as a result of those countries’ civil wars.

When, toward the end of the final year of my H1-B visa, the employers at the publishing firm where I worked decided to retain me and file a green-card petition on my behalf, I viewed it as a righteous victory. I’d stuck to my ideals and won. But, there again, I wasn’t thinking like a savvy immigrant. The September 11th attacks had taken place less than a year before, and little did I comprehend the enormous impact that event would have not only on my effort to remain legal in the United States but also on how my name and identity as a Muslim would be perceived.

As I wrote at the time, I watched as my name went from the coolest on the planet to the most vilified, at least in America. Meanwhile, by the time my employer-sponsored green-card effort was in the works, immigration had all but placed a moratorium on processing the petitions of Muslim applicants. The company’s legal representatives informed me that, due to a new directive, I would have to undergo a security clearance in order for the petition to be approved for further processing. I panicked, and sought the counsel of a private attorney, who confided bluntly to me that, given the post-9/11 political climate, he doubted my petition would ever be approved.

For the next eight years, I spent each month thinking that it would be my last in the United States; at one point, I earnestly considered packing up with my family and moving back to Ghana. My company, after getting its employees to train new content analysts in Mumbai and Manila, was downsizing its staff. In the spring of 2007, in what had become an annual rite, heads were severed in the editorial department, and my name was on the list of employees scheduled to be fired. But the director, to whom I am forever indebted, allowed me to stay with the company until the approval of my immigrant petition.

It was during this anxious time that I chanced upon the idea of applying for an EB-1 visa, also known as the “Immigrant with Extraordinary Ability” program, which confers an honorary permanent residency and a clear path to citizenship on individuals who have “demonstrated extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics through sustained national or international acclaim.”

These “geniuses,” according to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Web site, “must provide evidence of a one-time achievement” (i.e., Pulitzer, Oscar, Olympic Medal). I seriously doubted that I had made a significant enough contribution to American culture to be considered for this exception, but, after looking at my modest body of work, my attorney encouraged me to apply, in part because it was my only option.

It would take two tries and an additional three years of daily worry before I got the call, early one February morning in 2010, informing me that my EB-1 had finally been approved. By the time my green card appeared in my mailbox, some six months later, I had overcome my aversion to becoming a naturalized citizen; the painful experience I went through, coupled with the need to secure a better future for my three young children, had taken precedent over my youthful idealism. But, as per immigration rules, I had to wait another five years before I could apply.

In the past month and a half, it has become increasingly obvious that a green card is no longer a sure protection against deportation or harassment by immigration officials. I am frightened of what the new Administration’s anti-immigration stance could mean for my dream of becoming a citizen, and for the dreams of my friends and extended family.

On Whatsapp, which functions as a Facebook for immigrants, I get daily messages detailing reports of physical violence against Muslims around the country, news of burnt-down mosques, stories about African immigrants who have already been arrested as part of the Administration’s ramped-up deportations, and videos of Muslim community leaders and civil-rights attorneys exhorting members of the community to take steps to protect themselves in these unpredictable times.

Another Muhammad Ali, the son of the former heavyweight champion, was recently stopped and questioned at two different American airports; on the first occasion, in Florida, he was held for two hours and asked about his religion, despite his protestation to officials that he is the son of an American icon and is himself a native-born United States citizen.

Personally, I am consoled by the fact that the current turmoil is not without precedent, and that just as the Germans and the Irish suffered discrimination and taunts of “Go back home,” in the eighteen-hundreds, and just as Jews fleeing Nazi Germany were denied entry, during and after the Second World War, this current, ugly period in American history shall pass. Like my late father, who had an unflagging faith in America, I know that this country is bigger than its fears or flaws, because for the past twenty-eight years I have benefitted from the support and generosity of Americans such as Janice Crockett, who, when I was an international student at a boarding school in Michigan, offered to let me live with her family and treated me as one of her own.

Or the wealthy Brooklyn landlord who, after meeting and buying lunch for me and my first New York roommate, another immigrant, from Chile, decided to rent a two-bedroom apartment to us, even though both of us were freshly out of college and jobless. Or the corporate director who decided to keep me employed for three years at a company that no longer had any use for my expertise, so as not to jeopardize the stability of a young man who believed, idealistically, that the country he’d embraced as his own would, in time, embrace him in turn.