File photo: The writer says witchcraft is a myth ravaging the lives of many Africans

File photo: The writer says witchcraft is a myth ravaging the lives of many Africans

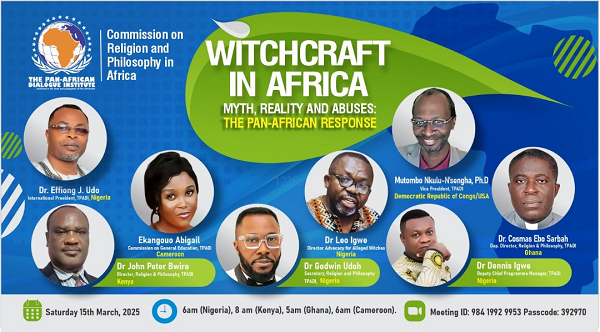

In this piece, I argue that witchcraft is a myth ravaging the lives of many Africans; and witch-hunting needs an urgent pan-African response. Drawing from the cases and activities of the Advocacy for Alleged Witches. I explore the myth and reality of witch hunting outlining ways to combat this menace and getting this continent out of this long socio-cultural darkness.

A pan-African response to witch hunting explores how to harness or apply African resources, material, mental, social, political, economic, and cultural to address the menace of witch persecution and killing. It is a response of Africans, to Africans, and non-Africans, by Africans, from Africans to the problem of witch hunts. I checked online for the meaning of a myth and found one: "a widely held but false belief or idea". Witchcraft is a widely held but untrue idea.

I rephrase it a little to read: witchcraft is a long and widely held but false belief or idea". I say so because some people validate witchcraft notions based on the number of people imagined to believe but also the duration. They allude to the fact that it is a tradition handed down from the past, an idea held by ancestors, for generations. But does that make a false belief true or a fictitious claim a fact? Not at all.

Witchcraft is a belief that some people have magical, occult, or supernatural powers that they use to harm others and cause accidents, sickness, and deaths in families. These people can disappear most often at night, they turn into birds, goats, snakes, and hyenas, to attend meetings in covens or inflict harm on others or their estate. Witchcraft belief also entails the idea that one can make incantations or perform some rituals in one part of the world most often in villages and kill or harm someone in faraway or nearby places, in the cities, or overseas.

Some people link witchcraft to their dream encounters, prophecies, and pronouncements by self-anointed and self-appointed pastors, priests, mallams and marabouts, diviners, and other self-acclaimed god men and women, custodian of ancestral and mermaid powers. These persons who claim to have supernatural powers mine and exploit fears and anxieties, people's gullibility, desperation, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities. In Calabar, Cross River state, a female evangelist, Helen Ukpabio, claims to be an ex-witch on a mission to identify witches and exorcize those possessed by witchcraft spirits.

She goes around organizing witch-hunting events and making people believe that child development challenges and other problems in families and societies are linked to witchcraft attacks. Some elderly women who have dementia and who are seen loitering the streets are mischaracterized as "flying witches" who crash-landed on the way to night meetings.

People who place palm leaves on disputed lands or those who use traditional religious objects to offer prayers are demonized and believed to engage in witchcraft. But witchcraft is not about occult beliefs or imaginaries alone, witch beliefs result in accusations and imputations.

Allegations of occult harm are made against real people in real time and space. Accused persons are made to confess; they are tortured into admitting to doing things that they never did, going to 'places' that they never went to, and perpetrating acts that they never committed. They are made to lie against themselves and others. The accused are tormented, beaten and flogged, threatened and intimidated, and coerced to implicate other innocent people, relatives, friends, and neighbours.

Accused persons, brothers and sisters, relatives including men, women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities in rural and urban communities, are forced to present themselves as natural beings with supernatural powers. Children accuse their parents. Parents accuse their children. The young accuse the old, the able accuse the disabled, the poor accuse the rich, and the rich suspect the poor.

The urban people including those living overseas accuse the village people. The village people suspect the urban, and overseas relatives of magically stealing their stars and destinies, of undermining their progress hence they are trapped in the villages.

In Ondo, a young woman accused the mother of being responsible for her problems. Some pastors told her that as long as the mother was alive her problems would not go away. In Imo state a man who blew some sand into the air in the course of a prayer on a disputed land was believed to have killed another family member who died in Vietnam. These widely held but false beliefs run rampant in communities. They underlie and motivate egregious abuses and violations.

Accusations are not innocuous faith statements or belief pronouncements. They have consequences and negative impacts on the lives of the accused. Witchcraft accusation is a form of death sentence, an incitement of hatred and violence against the accused. Accused persons are most often treated with indignity, without mercy and compassion. Alleged witches are humiliated and disgraced. They are denied basic rights and freedoms including rights to life and freedom from torture and inhuman and degrading treatment. They are beaten and flogged like animals. They are tortured, stripped naked, or set ablaze. Accused persons are buried alive.

They are banished and dispossessed. In Malawi, accused persons are stoned to death or lynched. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, witch hunters seize their cattle and belongings, they confiscate houses and farm products or set them ablaze. Accused people suffer extortion and are made to pay heavy penalties for committing no crime.

In Nigeria, alleged witches are abducted from their homes, and disappeared. They are subjected to jungle justice and trial by ordeal. In Liberia and Gambia, they are forced to drink poisonous concoctions that lead to health damage and death. Recently some persons accused of witchcraft were charged in court in Zambia. At the moment, they are being tried in secret. In the Central African Republic, they flee to stay in prisons to avoid being killed.

In Ghana, they take refuge at make-shift shelters popularly known as witch camps. In Ghana, a young woman along with a female diviner beat the grandmother, Akua Denteh to death some years ago. In Nigeria, another young woman accused and subsequently set the mother ablaze.

A compelling pan-African response must be predicated on a true representation of African culture and identity because there has been so much misrepresentation of Africa due to misguided scholarship by quasi-intellectuals and Africanists. I read a book many years ago that described Africa as a 'witch-bound continent'.

Incidentally, many African scholars and people have unwittingly embraced these misrepresentations. For instance, some people wrongfully argue that witch-hunting is a part of African culture. It is not. Of course, I have met some Africans who told me: "We kill our witches". When I tell them that I don't believe in witches or in witchcraft, they would ask: Are you not an African? As if being an African implies that one must believe in witches and wizards.

One must not. In Ghana, some people told me "We have our witch camps and we take them to witch camps". They make these propositions as if killing witches or banishing them to 'witch camps' is something to be proud of or something to be boastful about. It is not. These measures are dreadful acts that are out of step with 21st-century norms. They are things to be ashamed of because witch killing or witch camping is rooted in false belief, absurdities and mischaracterization. There are no witches or witch camps as popularly believed.

A pan-African response to witch-hunting must eschew these false premises. Witch hunting is based on fear, ignorance, and mistaken ideas. And making false accusations is not a part of the African culture. Witch hunting compels people to lie against themselves and others. It gets them to bear false witnesses against neighbours and relatives. That is not a part of the African culture.

Banishing and lynching people based on false allegations are not a part of the African culture. Killing the elderly, children, or people with dementia and other mental health challenges who need love and care is not a part of the African culture.

In conclusion, witchcraft is a myth doing real damage to the lives of people in Africa. All Africans must rise to the challenge of combating witch hunts everywhere. Let's for a moment assume that by some stretch of cultural imagination, reason, or unreason, witch-hunting is a part of the African culture. Is culture not dynamic? Are there no harmful traditional or cultural practices?

Was slavery, or human sacrifice not cultural at some point in history? That something is cultural does not mean it cannot change or it cannot be changed. Culture evolves. Society evolves. Why are many African societies still trapped at the first stage of August Comte's theory of human development, while the third positive stage beckons?

So a pan-African response to witch hunts entails a realization that culture is not static, that cultural practices change over time. African culture should be envisioned using the latest knowledge and information looking forward and not backward, looking to the future not to the past. The situation calls for an intellectual awakening, cultural reform, and rallying against witch hunts and other harmful practices.

A pan-African approach must reject a romanticization of witchcraft or witch hunts; it must repudiate the 'anthropological proposition' that witch hunting serves a domestic purpose, fulfils social stability and value; that witch hunting is a way Africans make sense of modernity in this post-colonial dispensation. It is not.