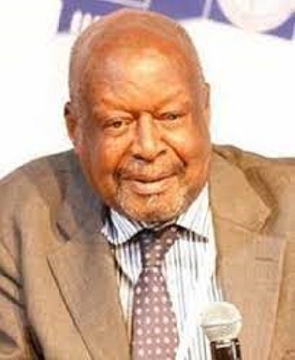

The late Uganda writer, John Nagenda

The late Uganda writer, John Nagenda

John Nagenda, who has died in Kampala, Uganda, aged 84, was one of the writers who emerged in Africa after their countries had gained their independence from Britain.

I met him at an African Writers’ Conference – the first of its kind – organised at Makerere University in 1962. From Ghana, the delegates were myself, Efua Sutherland, and Kofi Awoonor; from Nigeria came Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Chris Okigbo; while South Africa’s delegates included Ezekiel (later Iskiya) Mphahlele, Lewis Nkosi, Bloke Modisane and Bob Leshoai.

For years, Africa had been arbitrarily divided into rigid geographical “grids” with Africans hardly ever meeting one another in person. So the Makerere conference enabled Africans to discover the persons behind the continent's plethora of geographical labels.

I remember what a thrill it was to meet black South Africans for the first time, having been exposed to their lives and culture, through DRUM Magazine (whose Ghana editor I had just become.) DRUM had been born in South Africa but had soon sprouted a host of “offshoots” in Ghana, Nigeria, East Africa, and Central Africa. So, I was pleased to meet Mphahlele, Bloke, and Lewis (all of whose bylines I had seen in the “mother” (South African) edition of DRUM.

I was late in arriving at the conference, but on arrival, Kofi Awoonor, a most sociable individual, passed on to me, the delegates who welcomed friendship, as against those who were aloof. The former included the brilliant poet from Nigeria, Chris Okigbo, and a young Ugandan writer called John Nagenda.

Friendship with John Nagenda was easily the most auspicious that I cultivated at the Makerere Conference.

The guy was full of life and fun. He was handsome, athletic in build, and extremely humorous.

He was amused at our reaction to the way Ugandans pronounced certain words in English, and taught us how Swahili had taken over certain English expressions; for instance, that what we called “roundabouts’ in West Africa, were called kipileftis in Uganda!

I re-encountered John Nagenda in England in the 1980s. As it happened, John too had left Uganda for political reasons.

Before going to live in England, he had achieved fame as the only black African to play in the Cricket World Cup of 1975. (He bowled for East Africa in a team made up of Ugandans, Kenyans, and Tanganyikans).

He described the experience as life-changing – just imagine (he said) “rubbing wrists” in person, as it were, with the likes of Vivian Richards and Michael Holding [West Indies], Imran Khan [Pakistan] and the other cricket geniuses that one had been seeing on TV!”

John fulfilled our Makerere Conference expectations and published a novel entitled "The Seasons of Thomas Tebo" and a children’s book entitled "Mukasa".

He was also influential in getting several fellow Ugandan writers published abroad.

During his days spent in exile in England, John helped to run a cricket magazine. I once met him at a pub near the magazine’s offices, one afternoon. He was surrounded by a bevy of lady admirers, who made sure that he didn't drink too much white wine, and that horses he fancied were worth betting on.

Around 1985, he called me and introduced me to a Ugandan politician, whom he wanted me to interview for one of the papers I was writing for in London – Chief M K O Abiola’s African Concord.

The Ugandan politician was a guy called Eriya Kategaya, and he was one of the top leaders of a party that had been formed by Ugandan exiles, called the” National Resistance Movement.” They wanted to seize power in Uganda through guerrilla warfare. I was skeptical, for Africa was littered with all manner of “revolutionary” movements at the time, most of them spending their time in European capitals and doing very little on the ground in Africa. But Eriya Kategaya’s modesty and apparent seriousness of purpose won me over, and I gave the story quite a good play.

Within months, the NRA had achieved victory in Uganda, and I was immediately sent by the London Observer to go to Kampala and cover the story. The new Ugandan Prime Minister, Mr Samson Kisekka, gave me an exclusive interview, and two of his sons took me into the Ugandan countryside to find out how much support the NRM had in the rural areas.

I was astounded to find that at a junction, a couple of unarmed civilians guarding a person who had sold to other people, rationed goods supplied to him for his family’s use.

Surprised, I queried: “But he can run away if he is being guarded only by unarmed men?” I queried. The guards shot back: “Run away to where?” I realised, then, that the NRM was a truly revolutionary movement.

John Nagenda became Senior Adviser to the NRM leader, President Yoweri Museveni. He has been ruling since 1986 – despite John advising him to retire, after “training” someone else to take over leadership of the country.

John died a month before his 84th birthday. He will be mourned for his intelligence and generosity, but above all, for his excellent sense of humour.

I am inconsolable.