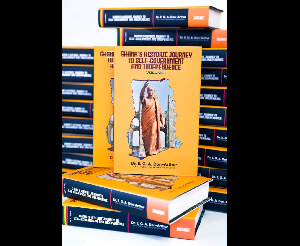

The cover of the book written by Dr Don-Arthur

The cover of the book written by Dr Don-Arthur

This book covers an epic journey of a people from a medieval past that sought refuge in a new land, then fell under bondage.

Thereafter they endured colonial subjugation and recently gained redemption to start anew as an independent people seeking freedom, justice and existence as a modern 21st century state in a pan-African world.

The trials, tribulations and triumphs in their quest for freedom and nationhood are centred on a contest between the best and worst traits of humanity as reflected in statesmen and clansmen that became trapped in a contest of wills.

The focus of their perennial battle through different epochs is between the common good of a people’s nationhood and the myopic narcissistic interests of fiefdoms that were mired in self-serving collaboration with imperialists.

Indeed, the very same cavalier Europeans to whom the native peoples had traded their gold, natural resources and even their very selves into bondage, now sought perpetual hegemony over the native peoples in the guise of evangelization, trade, protection and eventually civilization in the likeness of their own image and way of life, within their global sphere of influence.

The author brings a fresh vantage point that does not simplistically blame the coloniser alone for these catastrophic events, rather he analytically examines in great detail the interactions between the native peoples and colonisers with regard to resistance and collusion in their fight for freedom.

The author’s approach provides unusual context, juxtapositioned arguments and supporting evidence that grant us greater insights for events of the eras preceeding colonialism, encompassing colonialism and post independence.

Remembering the Future...

This approach inevitably throws up champions and villain’s alike.

It is up to the reader to discern the validity of their respective motivations and justifications given the ensuing results and outcomes of the strategies, interventions, institutions and methodologies they deployed.

This book is not just a national record of historical events, it is a living testament to the dynamics of relationships that formed the character and spirit of our nation.

Its beauty and ugliness are displayed in equal measure, above all the inherent tenacity and determination of the people shines through even in the darkest of times.

It took native individuals of great intellect to discern that the true nature of their struggle was a total liberation of the people to make them worthy of a new nation.

It took great ambition and total dedication for a heroic leader with stellar qualities to mobilize and lead a mass rebellion that mounted a determined challenge to an oppressor who had at its disposal and control, more than half the entire world at that time.

Whilst the battle may have appeared won at the point of emancipation and then independence, the war actually persists in an even more sinister form now.

Today, the nation’s interests are under threat of being permanently subsumed by partisan parochial interests that seek not the good of the many, but rather the best for the few.

A partisan diarchy has taken on many of the regressive characteristics of the fiefdoms that sought only their own promotion at the expense of the nation’s progress and prosperity.

Don-Arthur’s book about Ghana’s journey to independence and beyond is an investigative treatise on the genesis of the loss of freedom of the people’s of the Gold Coast to European fortune seekers through chicanery, enslavement and colonization of native fiefdoms.

The ensuing struggle of these people’s for their liberation, first from the shackles of slavery and then from the subjugation of colonialism is revealed with candour and a courage that is rarely seen and read.

The author freely admits that it took two to tango and thoroughly examines the role of caboceers, collaborators and co-extortionist that threw their lot in with the imperial colonialists and turned their backs on fellow native peoples whom they deemed their subjects or at best their rivals.

The book is a compendium of factual events relayed in the context of the lives and institutions of society during the various epochs, from precolonial Gold Coast, the colonial era and post-independence Ghana.

This book has affected the way I now view these periods in history because it is not a simplistic portrayal of villains and heroes.

The author rather carefully weaves a web of intricate relationships between the government of the day, the rulers of fiefdoms, the mercantile class and intelligentsia, and the larger group of workers, artisans and farmers that formed the bulk of the masses of nascent liberation organizations before, during and after the colonial period.

The author’s thorough and detailed research work brings clarity to the many misconceptions and falsehoods that I and many others, may have hitherto held about the conflicts between rival organizations, institutions and personalities.

The Aboriginal People’s Rights Society (APRS) and the Native Councils of British West Africa (NCBWA) gathered at various times to challenge and contest pivotal laws and arrangements that would have strengthened, deepened and or extended the colonial government’s rule and deprived native peoples of land, rights and freedoms.

The author charts with incisive alacrity the main conflict that developed between native institutions that sought to protect their people’s rights and interests, from usurpation by imperialist rule and its allies from the elite traditional ruling authorities.

This main conflict transitioned into a heated rivalry between the respective champions of these two competing sides even as the two organizations evolved into political parties leading up to independence and beyond.

The United Gold Coast Convention dissolved into the Convention People’s Party lead by Kwame Nkrumah and United Convention Party led by J.B Danquah.

The two have since become the dominant rival political traditions that have occupied Ghana’s post-independence political space under different names and different dispensations.

The book reveals the root causes of the major tensions that grip the nation, especially during elections when power is at stake.

It allows the reader to appreciate the high stakes involved in a game of supremacy that goes beyond mere electoral outcomes.

The gravitas of the contradictions of multiparty democracy aiding an agenda of ethnic hegemony is obvious for all to see.

The question is how long can our democracy in the fourth republic persist?

And what should be done to mitigate its ever increasing effects of divisiveness, nepotism, and a dispiriting lack of meritocracy.

Subsequent volumes of the book may perhaps delve deeper into this tendency and elucidate for us its impact on our fledgling democracy.

The insights of the author into the deep psyche of Ghanaian political traditions has been beneficial for the understanding of the limitations of the system as it currently exists, even though it has made significant contributions to our growth as a nation.

Readers must make up their own minds as to whether the evidence provided in this book is fair, truthful and accurate.

Readers cannot however avoid the incontrovertible evidence adduced from colonial archives, national records and even contemporary literary works, many of which are recorded speeches, letters and publications by the two key protagonists of the era, Kwame Nkrumah and J.B. Danquah.

The author leaves no doubt as to the albatross that hangs around the neck of our nascent nation and the need to deal with it if we are to progress beyond our current state of development towards a modern 21st century economy that delivers the dividends of democracy as prosperity for all and not just a few.

The elephant in the room that sits squarely as an impediment to national progress has a familiar face and attitude, the pursuit of self-serving narcissistic hegemony over others.

If nothing else, the book helps us to understand how this mindset has cost us in the past and is set to do so again if we do not make a deliberate effort to avoid it and benefit form our own experiences.

This book is both a historical account and investigative narrative of a tumultuous period in Ghana’s journey to nationhood.

It is a careful and thoroughly researched work whose assertions are supported by evidence gleaned from a variety of sources with the enthusiasm of a sleuth. Its arguments about the central conflict between the greater common good and parochial interests, between peoples, institutions, and leading personalities convey the impact of key decisions and events that shaped modern Ghana from the precolonial period and the colonial period to the post independence era.

The author’s method whilst repetitive, elucidates with clarity the various unintended consequences of groups with parochial interests seeking to establish hegemony over others at the expense of people and the nation.

The author reveals with uncanny intrigue the consequences of such hegemonic tendencies in different epochs.

His pursuit of the protagnants, with the determination of a badger, unveils long-concealed secrets and clandestine intent, whether it be by monopolizing trade with Europeans in the precolonial era, or by usurpation of colonial power for fiefdoms, or by concentrating partisan political power illegitimately, and by seeking factional dominance through dynastic succession in a dysfunctional democracy.

The book stands out for its extensive high quality research and analytic argument’s providing new context for an age-old debate, of what might have happened if the key characters had made different choices at pivotal times during this epic journey.

The author opens a window into different epochs that are often misunderstood because of simplistic bias and insufficient information.

His investigative analysis leads to a decisive characterisation of angels and villians during these epochs.

His perspective is continually focused on what would have been in the best interests of the embryonic nation.

It is my considered opinion that the author is not judgmental but seeks to understand the motivations and perspectives from which institutions and individuals operated in a shared struggle.

There is a consistent juxtapositioning of the greater good and parochial interests throughout the book to demonstrate its consequences but not to judge its merits.

This is evidenced by the dialogue between the two principal characters and their speeches.

On the one hand a nation building pan Africanist in the form of Kwame Nkrumah contrasted with J.B Danquah, a man bent on hegemony of his Akyem Abuakwa Asona clan and its ascension to the commanding heights of the nation.

The two could not be more different in their outlook, purpose and mission.

Reading this book has enlightened and deepened my understanding of the compelling motives behind key actors at critical times during our first contact with Europeans, during the colonial period and post-independence.

Whilst the major contrast between the African and European people is readily perceived, the ensuing dynamics between the African people and their collective engagement is more complex and took centre stage in the journey that became our story.

The intense focus of this story and revelations about Akyem Abuakwa Asona clan will shock many readers.

I hope other readers will take this investigative sleuthing of history in good faith and not assume that the author has an axe to grind.

The many evidences and references to independent sources that debunk attempts at historical inaccuracies, implicit misinformation, and in some instances contrived lies, emanate from factual accounts that are balanced and cross referenced with diligence by the author.

The deep dives into historical epochs through accounts that capture the mood, context and motivations of actions and counter actions by the principal characters portray the central conflict between two statesmen of an era.

One was to leave an indelible mark on the soul of our nation and the indomitable spirit of African people.

The foundations laid for Ghana and the cracks that developed in it had a profound effect on our nation then, even now and possibly in the future.

The origins of contradictory clashes that were set in motion a long time ago, only become clear through the fearless, erudite and methodical investigation that distills and lays bare ungarnished and often ugly truths, some heroic and others dastardly.

I highly recommend this book to students of History, Economics, Political Science and Journalism.

It is also a book of general interest to all readers that wish to gain a better understanding of the realities that have shaped our nation, because truth matters.

It is my fervent hope that going forward, the truths unveiled will help Ghanaians come to terms with the inherent tendencies that are a reflection of motives that have woven their patterns in the tapestry of the history, culture and ideology of our dominant political traditions.

Voters and ordinary citizens should also get a better understanding of why they vote the way they do and why their elected leaders behave like princes.

It is my hope that armed with the information and demonstrated arguments made by the author, Ghanaians will seek to have a common understanding for a new beginning.

Time does not allow us to reverse the clock, but it can provide the foundation for a new beginning that will enable us to reach greater heights in our national endeavours.

This is an excellent book that is in a category of its own.

It is a first because the author has been bold and candid in confronting very uncomfortable truths.

At the same time he has aired multiple points of view and facilitated a debate between competing traditions and their points of view.

I also highly recommend this book to those that have an appetite for jettisoning long held misconceptions that were only half baked, or discoloured by an intentionally misconstrued popular view.

Many will feel relieved to benefit from the authors studious monumental effort to get at the truth.

Others may likely find this book deeply upsetting and perhaps perceive it as a deliberately calculated undoing of the fabric of their history.

Who is to say what is truth and what is myth?

Students of life will all know by now that facts alone do not define truth.

Whatever the perceptions are, I foresee a tsunami of rebuttals.

However, as many such rebuttals as can be mustered will likely crash on the shore of truth, only to recede back into the bowels of the malevolent seas from whence they came.

I can say with certainty that after reading this book I will never look at Ghana the same way again, I suspect many readers will have an alternative view too.

Dr. Michael Abu Sakara Foster Agronomist and one-time chairman and presidential candidate of the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) of Ghana.

PREFACE:

The insightfulness of the patriotic words of the composer, James Russel Lowell, in the Methodist Hymn 898, is very instructive.

It is undoubtedly a great song.

The first stanza which starts with these words:

“Once to every man and Nation, Comes a moment to decide,

In the strife of truth with falsehood,

For the good or evil side”,

invokes positive reflections on the conscience of humanity.

The moral lessons in the hymn uplifted and spiritually inspired the author, as a matter of principle, to take up an unwavering, honest and sincere appraisal, to lend support to truth at all times.

Hence the courage to take up the writing this book, 'Ghana’s Historic Journey To Self-Government And Independence', so that we can remember the future and say it as it is.

Admittedly, the inspirational words of the song: “To Every Man And Nation”, which is a direct call to the conscience of humanity, positively fired the imagination and set the God-given 9th of the Ten Commandments:

“Thou shall not bear false witness” … or “Do not lie”, in the mind of the author ablaze.

The living message in the song charged the author to surge forward to confront falsehood.

Fortified with its inherent sacred principle, an uncowed and uncompromising principle, he did that which was noble.

He stayed on the path of truth to search for the real truth of our nation Ghana’s past, in Africa and around the globe, to get a better understanding and not seek knowledge in the firmament, to establish and proclaim the name of the actual person who was and still deserves to be recognised and acclaimed as the real founder of modern Ghana.

Remembering the Future...

He was determined even to go beyond the pale of verisimilitude in the strife of truth with falsehood if need be.

The overall goal is to establish the real truth in its general form and content, specifically concerning the history of the liberation and birth of modern Ghana.

The second and the most important task is to expose the falsehood being told and written by some historiographers about the political independence of our modern Ghana and to correct same.

Saying it as it was and as it is.

Truly the song; MHB 898, gave the author all the encouragement needed to put together this work, to the Glory of the Lord and to the eternal memory of the leader of the true liberators; the founder of this Republic of Ghana, land of our birth.

For it is already clear, that to be on the side of truth is noble.

The four stanzas of the hymn are presented here for those who would want to be on the side of truth, and catch the sacred fever in its verses:

“Once to every man and Nation, Comes a moment to decide,

In the strife of truth with falsehood, For the good or evil side;

Some great cause, God’s new Messiah, Offering each the bloom or blight,

And the choice goes by forever, ‘Twixt that darkness and that light.

Then to side with truth is noble, When we share her wretched crust,

Ere her cause bring fame and profit, And ’tis prosperous to be just;

Then it is the brave man chooses, While the coward stands aside,

Till the multitude make virtue, Of the faith they had denied”

By the light of burning martyrs, Christ, thy bleeding feet we track,

Toiling up new Calv’ries ever with the cross that turns not back;

New occasions teach new duties, time makes ancient good uncouth,

They must support still and onward who would keep abreast of truth.

Though the course of evil prosper, Yet the truth alone is strong;

Though her proportion be the scaffold, And upon the throne be wrong;

Yet that scaffold sways the future, And behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow, Keeping watch above his own.

The traditions, religions and beliefs which define the content of the national culture and character of the peoples of Ghana, the mainspring of their actions, strongly frown upon falsehood and dishonesty, as well as a lack of knowledge and ignorance.

These two abhorrent factors are identified as the bane of public and national life, as well as development efforts.

They pose an obstacle to access to true knowledge, denial to healthy discussion, moral progress and to overall prosperity in the life of society.

To propagate and to be on the side of falsehood in the Ghanaian tradition is deemed as unconscionable conduct and unacceptable behaviour, as it is an evil and sin against the moral fabric and consciousness of the people of Ghana.

Ghanaian society: the Guans, Akans, Ewes, Ga-Adangbes, Dagbanes, Mamprusi’s e.t.c., is very religious.

The society, as a whole, generally places immense value on truthfulness, frankness and forthrightness.

It demands of each and everyone to be bold in always saying it as it is.

“When you say it is water it should be water and when you say that it is alcoholic drink it should always be alcohol, to wit, let your yes always be truly yes and your nos always be no.”

With these commanding words every Ghanaianborn child is ‘outdoored’, initiated and admitted into Ghanaian society by family heads.

Good character training, as a cornerstone of society, based on ordered behaviour and on honesty, as precious family values and heritage, are passed on, inculcated and instilled in the child from a tender age through to adulthood.

This traditionally was and remains the norm.

During the period of adolescence he or she is introduced to the art of laconicism; taught in the use of proverbs to say much in few words and not to lie or exaggerate.

Asempa ye tsia, Obrapa gye owura kwan, Etu edur bon a ibi ka wo ano, edua nkwankwansa edurow a ofir wo nan ho, Dzin pa ye sen ahonya etc.

However, the art of laconicism being part of our Ghanaian nature and being, notwithstanding, it must be noted that these days the ‘doubting Thomases’, question every truth, with hired historiographers and revisionists busily engaged in rewriting and distorting the true history of the nation of modern Ghana.

The author in this book is thus compelled to occasionally repeat already stated facts where and when deemed strategically necessary to interconnect evidential and factual materials, making references to some tangible historic records or events, both forgotten and seldom spoken about, to elucidate or buttress a point of fact in order to reveal misrepresentations and falsehoods.

Recovering and not leaving relevant pieces of lost information of historic significance and modern history to rest enriches our knowledge so that we might not falter.

None of the materials ignored or pushed under the cornerstones and keystones of our pre- and post-colonial past struggles, on the way towards the establishment of a unitary state and nation are left unturned and unrecovered.

Thus the reader in this book will for the first time familiarise him or herself with some of the concealed and suppressed vital information to discover whether or not the true history of the country in actuality establishes that there was really an exclusive group or class of some special men – cream of the cream of society – who freed and founded the modern nation Ghana.

Or, on the contrary, if it indeed took an ordinary individual young man, a native, to provide the right political organisation and leadership to lead the subjected people of Gold Coast to free the country and themselves from the yoke of colonialism and imperialism, and to found the unitary state and modern nation Ghana.

The annals of modern day Ghanaian history has it that the first Founder’s Day anniversary was celebrated by the people of modern Ghana on 21st September 1958, to mark the anniversary of the birth of the leader who had brought the country out of colonial domination and thraldom.

The author is hopeful that the reader will learn more about who the nation’s principal architect cum master-mind of selfgovernment of our modern Ghana was and the roles played by other prominent personalities to frustrate the advancement of the peoples’ efforts towards freedom.

The reader will further learn more about the key, yet forgotten aspects and facts of our historic journey towards establishing the modern nation Ghana, and why Danquah and his group was livid with Nkrumah and his vanguard political party.

This approach will provide us with the potent inoculation against the contemporary problem of historical amnesia.

The first and second stones of historic significance from our recent past, one immediately after independence, and the other on our journey towards complete and absolute self-government, are revisited and overturned as they are obvious precursors for interpretation and determination of the reader.

Barely three months after the declaration of Ghana’s independence, on Monday, June 16, 1957 “at a conference held at the home of Dr. J. B. Danquah in Accra …, the National Liberation Movement and its allies demanded that the Queen’s (Elizabeth II) head be placed on the national currency (coins and notes) of (modern) Ghana and not that of Premier Nkrumah”, the dailies reported[1].

What a shameless act.

Let it also be remembered that, at that time, Ghana was a British Dominion: a self governing country of the British Commonwealth.

The Queen of England was the Head of State of modern Ghana and Her Majesty’s official local representative in the country was Governor Sir Charles Arden Clark.

There exists no evidence or record to show that at the time the Queen or the Governor had objected to the idea of printing of new currency by the Nkrumah government.

Again, in the month of February 1960, when a government sponsored parliamentary law was passed vesting parliament with the functions and rights of a constituent assembly to draft the constitution of the first Republic, the opposition led by Dr. Danquah and Prof. Busia accused Nkrumah of rebelling against the Queen of England and the Premier of striving to become a dictator[2].

Awesome! What can one say?

These unfortunate occurrences, impediments and statements, were calculated to sow the seed of doubt and confusion.

As a result, during the time of the liberation struggle from colonial domination, the ‘Black Sirius’, Nkrumah’s, unwavering stridency in pursuit of total self-government and positive institutional transformations to give a meaningful expression to the achievements of the masses and to encourage them to continue relentlessly with the patriotic struggle for complete political freedom and absolute independence from the British colonial powers got him into trouble with the fearmongering opposition intelligentsia group led by J. B. Danquah.

The opposition was of the opinion that the country, colonial Ghana, was not ready for self rule and independence.

For them, the country would be much better off if the British colonial government stayed on to rule, administer and continue with the colonial experiment in the country[3] .

The conservative intelligentsia with some of the powerful influential Chiefs: agents and accessories of indirect rule, were comfortable with the colonial experiment and rule.

They therefore teamed up to resist the idea of granting of full self-government which the ‘Black Sirius’ with the masses were diligently pursuing.

They demanded that it should be delayed for a little bit longer.

The people of colonial Ghana, however, were already awakened by ‘Sirius’ to the fact that political freedom was a necessary key to national existence, peace and prosperity[4].

1. Graphic JUBILEE GHANA, A 50 year new journey for Daily Graphic, 17th June 1957, p.16

2. Yuri Smertin, Kwame Nkrumah, 1987, p.110

3. Yuri Smertin, Kwame Nkrumah, 1987, p.94 & 95, Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana, The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah, 1957, p 279

4. Kwame Nkrumah, I Speak of Freedom, 1961, p.17

INTRODUCTION:

“A crab does not beget a bird”.

This is an ancient Ghanaian saying. It is a verifiable fact. It is popular among Ghanaian proverbs. In essence it asserts that ‘like father, like son’.

So, in nature, the DNA of a crab is naturally passed on to its offspring.

A crab begets a crab. Ergo, genetically the characteristics and behavioural traits of parent crabs are no different from that observed and seen in their offspring – food for thought.

Occasional oral recollection, and persistent demand by traditional institutions in Ghana to observe, celebrate and commemorate events helps to embed this.

They are by and large associated with the outcome of past inter-tribal rivalries, hostilities and wars for capture of territories or land grabbing; for supremacy, subjugation and dominance by our forebears, and are commemorated annually at tribal cultural festivals.

They are reminders that are more often than not problematic.

In the final analysis these customary and traditional activities invariably produce, instill and pass on generational traits of blind loyalty, subservience, servitude – ‘like father, like son’! It is necessary to observe in nature the interaction of carnivorous predators with their prey e.g. of lions with gazelles or with antelopes, and of foxes with hares, rabbits or with fowl.

In each separate scenario is an interrelation of complex organisms.

The predators, aggressive as they are, are carnivorous.

These predators will always hunt. They will by nature.

They ambush and attack their prey, and kill and devour them with relish whenever they desire for existence.

On the other hand, the vulnerable prey will out of fear instinctively flee from the danger and from the inevitable consequences of the attack to preserve their lives, to survive.

“A decisive role here, in each case, is played by behavioural reactions which are the result of higher nervous activity”[1].

The act or habit of predators preying on, hunting and killing other species of animals for food is as innate as a natural inborn phenomena.

As their parents were or are carnivorous by nature, so they are also.

However, without doubt, the human trait sets us farthest apart from the animal kingdom thanks to the extraordinarily overdeveloped and most prized region – the cerebral cortex of the human brain.

Among humans, it must be stressed that habits and skills are generally not innate but are taught.

They are lessons learnt and acquired by instruction and experience gained from parents at home through nurturing, at work places and through influence in and from the community.

Charity and discipline basically are taught and acquired first from home and then from the community at large – food for thought.

Long after the fall of the Ghana Empire our ancestors who had found a new haven for themselves here in the Gold Coast/colonial Ghana embarked on a historic journey from pre- colonial days until today, as a constitutional democracy.

Given its many decades of nation building efforts, peaceful, violent, voluntarily or by force, every generation played and continues to play its part.

So also do individuals who perform and offer exceptional duties towards the realisation of the nation’s short and long term dreams.

The contributions of exceptional individuals throughout this historic journey need to be highlighted in the midst of antagonism, or else, we risk being led into a future where no one feels an obligation to render exceptional service with honour.

Having regard to the fact that our forebears played different roles in building Ghana to where we find it today, the author of this book spent significant time researching into the historical past, and conduct and action, as well as inaction, of past leaders who had had opportunities and the responsibility to render memorable service to this nation.

In all that you would read, efforts were made to back every claim with evidential accounts from history books, publications and materials to reveal the scale of contributions made by past leaders.

I have also sought to afford you the opportunity to come to the conclusion yourself that some individuals took this country more personally and gave their all in the struggle to see the aspirations of the people materialize.

As a people and nation, civilised as we are, we need to aspire to live and work together in unity, in peace and in prosperity for all.

With mutual trust, we must strive to generously live in fellowship with each other. In unison and with one accord, our forefathers positively responded to the call for freedom, self-government now! and for independence, and from that a nation was born.

And immediately thereafter our Republic was created in unity, for sustained progressive growth and stability.

Given where we have gotten to, after more than sixty-five years of our nation building endeavours, we owe it as a sacred duty to restore and renew the spirit of national unity as Ghanaians to experience the dreams of our founders.

Let us then abandon and abhor tribalism and ethnocentrism, including all those tendencies that have culminatively held back development and progress over the years since.

1. M. M. Kamshilov, Evolution of the Biosphere, p. 21

ghanahistoricjourney@gmail.com