CDD, a governance-focused think tank in Ghana, recently held a meeting at the University of Ghana Business School on corruption. It did so in partnership with the Ghana Integrity Initiative, IMANI (with which I’m affiliated), the World Bank, Ghana Anti-Corruption Coalition, ACEP (a frequent IMANI collaborator), GRASAG, and others.

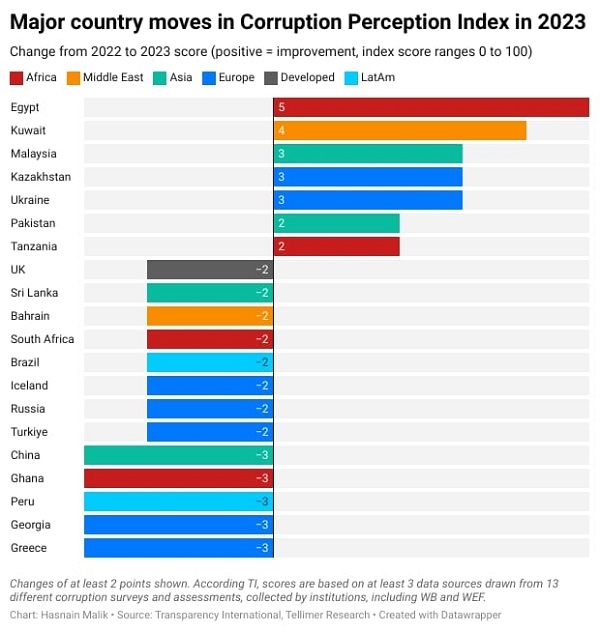

The meeting coincided with the release of Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. Whilst local analysts have interpreted results of the latest index as suggesting “stagnation” in Ghana’s fight against corruption, International analysts say that the country is actually one of 5 emerging markets that have seen a significant deterioration over the last couple of years.

The meeting also provided the occasion to launch CDD’s latest AfroBarometer survey on corruption, but with a focus on citizens’ concerns (Transparency International tends to focus somewhat more on the perceptions of elite actors).

I was asked to deliver a short presentation on one of the event’s themes: “state capture”. Dr. Daniel Kaufmann, a former Chief of the Natural Resource Governance Institute and long-time (anti)corruption guru, who spoke afterwards, also announced a fresh revamp of the state capture index.

State Capture is too complex a topic to do justice to in a brief talk. So, I focused on a twist to the classic framing.

Building on a long line of literature touching on related ideas such as “elite capture” and “state predation”, experts at the World Bank in the late 1990s seized the opportunity presented by transitioning economies in the post-Soviet space, where once public corporations were hurriedly privatised leading to the rise of “oligarchs”, to craft a new discipline for probing the phenomenon of state capture. State capture manifests through efforts by economic elites to shape public laws and institutions to advance private interests in ways that can lead to “legal corruption”. I argued that Africa’s context was not too fertile for this idea to take analytical root.

Unlike the former Soviet Union, private economic activity in most of Africa was always heavily informal and widely perceived as “suppressed” or “repressed”. Private sector oligarchs “capturing the state” was thus rarely a headache for many an observer. Within that haze and fog, something else evolved in Africa that I prefer to call “state enchantment”, a process of hypnosis of the masses and economically non-powerful elites involving private interests perverting “national success” narratives to disguise parochial underlying private interests.

Whilst some of these interests may well be inimical to public welfare, the projects of state enchantment are so elaborately disguised that the public is unable to appreciate even the presence of commercial motivation behind the new laws, policies, projects and institutions being created to push the particular enchantment effort.

I also gave examples especially relevant to Ghana.