Senyo Hosi is an economic policy analyst

Senyo Hosi is an economic policy analyst

As a father of two with others I care for, I am clear that my spending is not aimed at generating profit for myself. Instead, it is to ensure these dependants have a social, economic, and spiritual life that makes them impactful and productive members of society.

As an entrepreneur, my expenditure is to deliver responsible profits for myself and my shareholders, along with a constructive economic impact that often requires patience to realise. I prioritise value delivery and development, focusing on short-term financial sustainability, with the hope that it will serve as a foundation for medium- to long-term profits. Although these goals are different, they are similar in that both aim to achieve their respective objectives.

The recent debate about the reported US$214mn loss by the BoG in its Gold-for-reserves programme, also known as the Domestic Gold Purchase Programme (DGPP), has been quite fascinating. It has been passionate, sentimental, and technical all in one. Some contend it is a loss, while others argue it is not. So, what exactly is a loss? Can't we simply agree on what a loss is? In economics, where strict science meets the complexity and flexibility of human nature, almost everything is ambiguous. Therefore, it’s not so straightforward but can still be honest.

That’s why, while ‘1+1’ equals two everywhere in the world, the success of an economic policy is not consistent everywhere. Even the mighty IMF and World Bank cannot guarantee a perfect outcome in their interventions. There is always an X-Factor.

1.0 LOSS OR NO LOSS?

From an accounting perspective, the establishment of loss is simply total revenue (TR) minus total cost (TC). If TC is greater than TR, you have a loss. In finance, there is sometimes a slight shift. Instead of TR or TC, you may be considering the present value of TR and TC, which may require a discount factor (in layman's terms, an interest rate) to determine. Let me give an example to explain: imagine investing Ghs100 in a venture at the start of the year and receiving Ghs110 at the end of the year. In accounting terms, you have made a Ghs10 profit. It is as simple as that. However, financial economics looks at it differently. It first considers the opportunity cost — what else you could have done with that money?. Let us say you could have invested in treasury bills or notes at 15% p.a. This means you could have earned Ghs15, not just Ghs10. Since you earned less than the Ghs15 you could have made, you have effectively incurred an economic loss. I am sure you will agree that that book long ‘na wahala’.

In economic policy, it is an entirely different game. Every economic policy intervention must be evaluated on its incremental economic value and aligned with its economic objectives. That is why expenditure on education is not viewed as a cost but as an investment to maintain the quality of labour, which in turn drives and sustains economic growth into the future. This explains why we discuss primary surpluses and deficits or economic costs and benefits, rather than accounting losses or profits.

Each economic policy intervention's impact, as planned, must align with the desired economic outcomes. For example, an economic policy of promoting exports through export subsidies (a cost to taxpayers) must align with its objectives, which may include inflation, exchange rate stability, GDP growth, employment, socio-economic equality as measured by the Gini and Human Development Indices, etc.

A loss in economic policy terms should be assessed based on the economic outcomes the intervention seeks to achieve, compared to the actual measurable results. The evaluation should consider not only the policy's costs but also its benefits.

Simply put, “an accounting loss or financial loss is not an economic loss! So not all loss be loss and not all profit na benefit!”

2.0 THE GOLDBOD

Prior to the formation of the GOLDBOD, one thing was certain: Ghana was not fully benefiting from its gold output. According to the United Nations COMTRADE, the United Arab Emirates imported USD7.1 billion worth of gold from Ghana in 2022 and 2023. Ghana, however, reported official data of USD4.8 billion. Using the UAE (a major importer of our ASM gold) as a benchmark, about one-third (almost 33%) of our production was smuggled and left unaccounted for.

In years past, Ghana had to rely on borrowed foreign exchange through Eurobonds and Syndicated Loans to COCOBOD to build its foreign reserves, mainly due to overdependence on primary exports. The underperformance of cocoa exports and the retention of export receipts offshore (part of Ghana’s stability agreement with foreign mining companies) by Ghana’s foreign-dominated mining companies meant that even if gold production and gold exports improved, it could not support the building of Ghana's reserve buffers. In the end, Ghana could not borrow itself into perpetuity and ended up with the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) and an external debt restructuring programme, which were integral parts of Ghana’s IMF-supported reforms programme under the broader debt restructuring programme.

The GOLDBOD was set up with clear monetary policy-related objects.

1. Generate foreign exchange for the country; and

2. Support the accumulation of gold reserves by the Bank of Ghana.

3. Oversee, monitor and undertake the buying, selling, assaying, refining, exporting or other related activity in respect of gold.

The policy rationale for these objects is to centralise gold trade, optimise forex inflows, accelerate gold reserve accumulation, and generate national benefits from the entire value chain of the country’s gold resources for economic revitalisation and sustainable growth.

Ghana’s GOLDBOD sources gold from mainly licensed artisanal and small-scale miners, using a regulated network of authorised buyers and aggregators. It pays in cedis based on the Bank of Ghana's reference rates and either exports the gold or allocates it to the Bank of Ghana for reserve accumulation.

3.0 HAVE WE REALISED OUR OBJECTS?

The year 2025 marked the inception of GOLDBOD, and in just one year, Ghana’s Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM) gold export value has increased from 63.6 metric tons (mt) in 2024 to 101mt as of 23rd December 2025. Reference is made to actual export volumes in metric tonnes to ensure that the current higher gold prices do not distort our analysis. It should be noted that this is not just a result of a significant surge in production but rather an optimisation of the accounting of Ghana’s gold production by drastically reducing smuggling. This achievement is due to GOLDBOD's work, and we must acknowledge their contribution. GOLDBOD and its practices have successfully optimised our ‘official’ gold trade.

According to the IMF, the BoG has had to recognise a trading loss of USD214mn (GHS2.4bn). This is undoubtedly an accounting loss. We are also told that it has been due to GOLDBOD disincentivising smuggling by buying at world market prices, thereby being unable to cover its operational costs. From a pure trading perspective, this does not make sense. The pricing strategy to offer world-market prices to miners for buying their gold output is to incentivise them to sell to GOLDBOD rather than to the foreign gold buyers who had become entrenched in the market and were offering prices 1-2% below international prices. This is thus an aggressive entry into the market to break the entrenched foreign dominance in Ghana’s gold trading market, without which the GOLDBOD would have struggled immensely to penetrate. Indeed, it is through this pricing strategy that smuggling has been significantly reduced, and Ghana is fully reaping the benefits of gold exports.

Thus, from a policy perspective, the USD214mn (GHS2.4 bn) trading loss must be viewed differently, not through a financial or accounting lens. For instance, the forex inflows from the reduced smuggling can be transformative and more beneficial to the broader economy, so incurring ‘the loss’ makes sense and becomes an economic policy cost required to yield greater economic policy benefits.

From what I gather in my research and interviews with market players, the ‘trading losses’ also arise from the differentials demanded by gold producers for the difference between open market exchange rates and the Bank of Ghana interbank rates used to price the ASM gold. To this, if the Bank of Ghana’s interbank FX rate is set at Ghs11.0 to US$1.00 and the open market rate stands at Ghs12.0 to US$1.00, producers will demand Ghs12.0, not Ghs11.0. GOLDBOD will increase its buying price to miners, often midway through the differential, through a ‘so-called bonus’ to ensure producers do not lose out on their market reality.

For example, if the world price is $100, the BoG rate is Ghs11.0 to US$1.00, and the open market rate is Ghs12.0 to US$1.00, producers will receive Ghs1,100. If the same producer sells his gold to a smuggler at $100, he will receive GHs1,200 at the open market rate of Ghs12.0 to US$1.00. To disincentivise producers from smuggling, the GOLDBOD adjusts its prices upwards by offering a bonus of about Ghs50 (often about 50% of the FX differential), so producers receive Ghs1,150 and minimise the risk of selling to smugglers. This ‘Ghs50’ is a major reason for the reported ‘trading losses’. This is effectively, a foreign exchange loss.

4.0 DOMESTIC GOLD PURCHASE PROGRAMME (DGPP): LOSS OR NO LOSS?

What we know for sure is that the DGPP policy operation through GOLDBOD has cost us USD214mn and possibly counting. Various explanations have emerged, but the fact is that GOLDBOD is a policy institution tasked with supporting the operationalisation of the DGPP's monetary policy intervention.

The IMF in its latest staff report stated that, “The scaling up of the Domestic Gold Purchase Program (DGPP) has allowed the BoG to meet its program reserve accumulation objectives, reaching the 2028 reserve coverage target in 2025.” That is a commendation by all standards.

Gross international reserves are always at the core of a currency's stability. So, the lower the Gross international reserves, the lower the value of a currency in a floating FX rate regime. The DGPP programme has led to an increase in the BoG’s gross reserves from USD8.98bn in 2024 to $11.12bn as of October 2025, and they are projected to reach about $13bn by year-end 2025.

The IMF, in its own papers, have attributed the nominal exchange rate appreciation to the building of reserves and our FX inflows, which is widely known to be driven by the surge in official gold export receipts. Our receipts have surged from two fronts.

1. The surge in official gold export quantity. We have recovered our one-third loss to smuggling by moving official volumes from 63mt in 2024 to 101mt in 2025. This is attributable to the GOLDBOD policy intervention.

2. Surge in global gold prices. Prices moved from about an average of $2,386/oz (LBMA data) in 2024 to $3,439.37/oz in 2025, marking a 44% increase.

Undoubtedly, the stars have aligned with our own actions to realise the blessings of the now.

Without any fear of contradiction, our foreign exchange bounce back has been a well-orchestrated home-grown strategy and alignment of monetary and fiscal policy anchored on the productivity of the GOLDBOD under the BoG’s DGPP programme! This is why any discussion of the cost of the GOLDBOD intervention must be carried out together with an evaluation of the enormous economic benefit to Ghana in 2025.

To evaluate the economic benefits of this policy intervention, we will examine these key indicators.

1. Impact on the USD/GHS exchange rate

2. Impact on Government debt service savings

3. Impact on Government’s foreign exchange expenditure savings

4. Inflation

5. The import bill

4.1 Impact on the USD/GHS exchange rate

Ghana moved from an actual BoG interbank GHS/USD average rate of GHs14.2 to US$1.00 in 2024 to 12.53 in 2025, marking a 13% average appreciation. On a year-on-year basis, Ghana moved from a year-end of Ghs14.7 to US$1.00 in 2024 to GHs11.2 to US$1.00 in 2025, marking a 32.47% appreciation.

What is most instructive is the average exchange rate forecast in the IMF’s supervised 2025 budget, which projected a depreciation of about 9%. The 2025 budget was built on the assumption of an average GHS/USD rate of GHs15.95 (which, to be fair, was about the street-market rate as of December 2024). GHs15.95, therefore, serves as the policy benchmark for any fair analysis of the performance of the policy benefits from relevant exchange rate-related policy interventions.

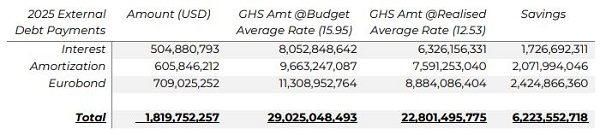

4.2 Impact on Government's external debt service

The table above summarises our external debt service position as at mid-December 2025. What it tells us is that our ability to reverse the trajectory of the Ghana cedi from a projected year average of Ghs15.95 to a realised average of GHs12.53 has saved the Ghanaian economy over GHS6.2billion. At year-end closing rates, this saving is USD560mn. This is not a profit but an economic benefit from GOLGBOD policy actions. As stated earlier, in economic policy terms, we focus on policy benefits and costs and not profits or losses.

4.3 Impact on the Government’s foreign exchange expenditure savings

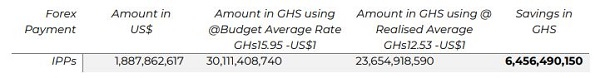

To assess this, we should ideally examine the government’s foreign-exchange-based expenditure and evaluate the benefits of the Ghana cedi's appreciation. These will include payments to independent power producers (IPPs), imports by government agencies and vendors, including capital expenditure vendors. Extracting this accurately may be complex at this stage, so I will stick to a single item I can pull out: IPP payments for 2025.

From the above we have realised a saving in excess of GHS6.45bn. At year closing rates, this saving is USD582mn.

4.4 Inflation

The IMF country director, Dr Adrian Atler, in a recent interview with Benard Avle of CitiFM, explained that the strengthening of the local currency has played a pivotal role in restoring price stability, helping inflation fall from 24% in 2024 to 6.3% in November 2025, which is the lowest level in four years. He further argued that the contrast between last year’s rapid currency depreciation and this year’s modest appreciation clearly shows how exchange rate management has shaped the inflation path.

There is no denying that the GOLDBOD-inspired currency appreciation is a major contributory factor to the BOG’s ability to reduce inflation from 24% to 6.3% as of the end of November 2025 (Ghana Statistical Service).

4.5 The import bill

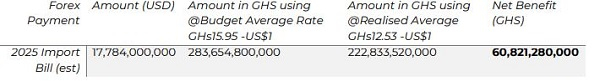

Ghana’s import bill is projected to end 2025 at about USD17.7bn. This projection is based on official January to October data.

From the analysis above, the comparative saving exceeds GHS60bn for the Ghanaian importer and consumer (including government consumption) and for the economy as a whole. This saving has improved the real spending power of Ghanaians, which Fitch estimates at +2.5% (as at June 2025), over 120% increase from the spending power growth of +1.1% realised in 2024. With inflation heading further down, we can only estimate a larger increase in the Ghanaian’s real spending power.

4.6 Summary

1. The appreciation of Ghana Cedis is foremostly a result of the BoG’s domestic gold purchase programme (DGPP) operated by GOLDBOD. In other words, it is a GOLDBOD-inspired currency appreciation.

2. The direct fiscal savings from the GOLDBOD-inspired appreciation are in excess of GHS12.6bn (US$1.142bn), more than 5 times the policy cost of US$214mn (Ghs2.4bn). Ghs6.22bn on external debt service and 6.45bn on IPP payments. If we were to add savings on import-related capex and goods and service expenses across the central government and state-owned enterprises, this would significantly increase.

3. According to the Bank of Ghana ACT, 2002 (ACT612), the primary object of the Bank of Ghana is to maintain stability in the general level of prices. Achieving 6.3% inflation from 24% in less than a year is a policy outcome success driven by its DGPP programme.

4. Over GHS60bn savings on our import expenditure have been realised and accrued to the economy.

5. The US$214mn (Ghs2.4bn) is a policy cost and not a loss, as its economic policy outcomes outweigh its financial cost.

5.0 THE IMF AND THE ‘LOSS’

Let us get it clear, there is no issue with the IMF flagging the US$214mn. It is their estimate of the policy cost. I do not subscribe to the view that the Bretton Woods institutions are haters and wreckers. If it were so, China would not be where it is today. Achieving all the economic benefits without spending US$214mn would have been ideal. These institutions will always push economies to optimise, and that is what they were doing.

Having said that, I am clear that the recovery is a shock to the IMF. A significant and swift depreciation is often the starting point of resolving a balance-of-payments (BoP) problem (Culiuc and Park, 2025). This is the view and expectation within the IMF, as duly captured by the authors who are IMF executives. In their study, which analysed worldwide data from 1971 to 2024, they concluded that “Equilibrium REER depreciations are largest when an IMF-supported program is put in place after the initial depreciation takes place.” Simply put, when countries enter IMF programs, the magnitude of currency depreciation increases, suggesting that depreciation is part of the adjustment mechanism.

Consequently, our currency appreciation is a surprise and an outlier because it happened too soon. Of course, it's commodity price-driven, without much structural transformation, but the stability is welcome. What they missed is the Ghanaian's behavioural nature and propensity to smuggle. There is no need to be antagonistic. Just like I said in the beginning, “while ‘1+1’ equals two everywhere in the world, the success of an economic policy is not consistent everywhere”. They are aiding us with what they know, and our homegrown policies must shape what they learn in ways that are practical and unique to Ghana. We have brains too! We are writing the rulebook in Ghana and not in Washington, and this is real progress!!! (to borrow from Harvard Economist Prof Dani Rodrik).

6.0 CONCLUSION

On the back of the realisation of the policy outcomes of low inflation, real fiscal savings and import bill savings, I do not consider the $214mn or GHS2.4bn spent on the DGPP a loss. It is a policy cost worth the spend if it was spent legitimately. Having said that, I must admit that policy must move to reduce or zero out this cost to enable us to maximise the economic benefit from the policy.

The existence and quantum of disparities between Bank of Ghana foreign exchange rates and open market rates are counterproductive and lead to foreign exchange losses. It is imperative that the BoG moves to converge the exchange rates on the market to eliminate room for foreign exchange losses.

In addition, we need to build resilience and transform the economy's structure to sustain the gains realised so far. We cannot continue to be commodity-dependent!!!

Economic policy is not accounting; evaluating its impact requires a more holistic approach, or we risk knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing.