Patrice Lumumba, Former Prime Minister of DR Congo

Patrice Lumumba, Former Prime Minister of DR Congo

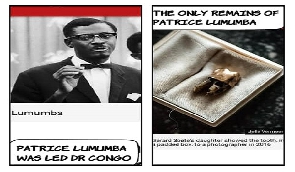

Cameron Duodu remembers working as a journalist in Ghana and documenting Patrice Lumumba’s dramatic rise to power - and subsequent assassination - from afar. In so doing he uncovers why Lumumba is such an important historical figure who 'was not assassinated merely as a person, but as an idea'. Patrice Lumumba is, next to Nelson Mandela, the iconic figure who most readily comes to mind when Africa is discussed in relation to its struggle against imperialism and racism. Mandela suffered tremendously. But he won. Lumumba, on the other hand, lost - he lost power, he lost his country, and in the end, he lost his life. All were forcibly taken from him by a combination of forces that was probably the most powerful ever deployed against a single individual in history. Ludo De Witte, in his book, ‘The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba’, calls Lumumba’s murder ‘the most important political assassination in the 20th century’. The amazing thing is that Lumumba had done absolutely nothing against those who wanted his blood. They just saw him as a threat to their interests; interests narrowly defined to mean, ‘His country has got resources. We want them. He might not give them to us. So let us go kill him.’ I insist, though, that he should not be seen only as a victim of forces too powerful for him to contend with. On the contrary, he should be seen as someone who fully recognised the power of the forces ranged against him and fought valiantly with every ounce of breath in his body and with great intelligence to try and save his country. Thus, we can see in the history of the African people’s struggle in the 20th century, Mandela and Lumumba representing the two ends of the pole that swung within the axis that marked the fulcrum of the struggle. The two men represent the beacon of light that shines sharply to bring absolute clarity into the evaluation of a history that is often mired in obfuscation and mendacity. To those who say, ‘How wonderful it was to see in Mandela, the issue of oppression so peacefully resolved’, we need only point to that picture of Patrice Lumumba, a torturer’s hand in his hair, as he was brutalised in a truck by black Kantangese soldiers at Elizabethville (now Kisangani). In that picture of Lumumba, serious students can espy unseen hands, steered by a ‘heart of darkness’, bribing, mixing poisons, assembling rifles with telescopic sights, and finally propping an elected prime minister against a tree in the bush and riddling his body with bullets. And then - could even Joseph Conrad, in his worst nightmarish ramblings, have imagined this? - first burying Lumumba’s body, then exhuming it a day later because the burial ground was too close to a road, and then hacking it to pieces, and shoving the pieces into a barrel filled with sulphuric acid, to dissolve it. And could Joseph Conrad have been able to picture the murderer making sure to break off two front teeth from Lumumba’s jaw, to keep as a memento to show off to the grandchildren in Brussels in years to come? As well as one of the bullets that killed him? If Shakespeare could write black comedy, we might have got dialogue like this: ‘Grandpa, what didst thou do in the Congo?’ ‘I exterminated Lumumba - and mark thee, that’s why I live in comfortable retirement and, never ye forget this - that’s wherefore ye went to such expensive schools. Here - see? Two of his very teeth that I broke off and brought home! And this - the bullet that finished the job!’ A Belgian, nearly 60 years after Conrad published his ‘Heart of Darkness’ and 57 years after Roger Casement and E. D. Morel had made what they hoped was a definitive exposure of the crimes King Leopold The Second of Belgium had committed against the Congolese people could still engage in such barbarities against a leader elected on the basis of a constitution signed into law by Leopold The Second’s own grandson, King Baudoin the first. That sordid crime in the bush near Elizabethville 50 years ago was the logical conclusion of a bitter and vigorous campaign that Belgium, aided by the United States, waged in the Congo in 1960 to ensure that Patrice Lumumba would never get a chance to rule the country that elected him to be its leader. Because of the action of Belgium and the United States, we actually do not know whether Lumumba would have made a good ruler or not. This makes him even more important to history: for he was not assassinated merely as a person but as an idea. What was that idea? It was the idea of a Congo that was fully independent, non-aligned, and committed to African unity. Lumumba’s party, the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), was the only one in the Congo to organise itself successfully as a party that saw the Congo as one country, not as a conglomeration of ethnic groups. Thus, it gained 33 out of the 137 seats in the Congolese Parliament. From this relatively strong base, Lumumba was able to inspire others with his vision and thereby hatch alliances that enabled the MNC to command an overall majority of seats in the Congolese Parliament. When Lumumba was appointed prime minister by the Belgians, many of the Belgians in the Congo and in Belgium itself thought the heavens had fallen in. For he was not the Belgians’ first choice. They tried other Congolese ‘leaders’ (such as Joseph Kasavubu) and it was only when these failed to garner adequate support that they unwillingly called on Lumumba. The magnitude of the achievement of the MNC in organising itself as a nationwide party, and managing to hatch viable alliances, is not often appreciated, because few people realise that the Congo is as big in size as all the countries of Western Europe put together. (As for Belgium itself, it is outrageous that it should have wanted to run the Congo in the first place - the Congo is 905,563 square miles in size, compared to Belgium’s puny 11,780 sq. miles. In other words, Belgium arrogated to itself the task of ruling a country more than eight times its size.) Not only is Congo huge, but think of a country the size of Western Europe that does not have good roads, railway systems, telecommunications facilities, or modern airports. And a Western Europe in which political parties are legalised only one year before vital elections. The only thing to add is that in the Congo, the first nationwide local elections held in 1959, which saw the emergence of the MNC, were even more crucial, for it was those elections that were to assess the strength of the various ‘parties’ (in effect, ethnic movements) that would take part in deciding the future constitutional arrangements under which the country would be governed. Who knew, perhaps the independence that Ghana (1957) and Guinea (1958) had achieved, might even come Congo’s way and those elected might become ministers, who would form the first government of a new, independent Congo, after nearly 100 years of the most brutal colonial rule inflicted on an African country by a European ruler. By the time the Belgians felt the need to call a constitutional conference in Brussels to decide how the new Congo was to be ruled, Lumumba was in prison. Again. (He had earlier been imprisoned on a charge of embezzlement while he was a postal clerk. It needs to be pointed out that the charge was brought against him while he was away in Brussels, touring the country at the invitation of the Belgian government. Was someone trying to blight a future political career? The charge on which he went to prison a second time was more in line with colonial practice. What was that charge? ‘Inciting a riot.’ Where have we heard that before? Those who know African history can immediately see the parallels with what happened in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi: it was precisely the same colonial criminal code that had put Kwame Nkrumah in prison in Ghana in 1950, and in a slightly more tortuous manner, Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya in 1953 and Kamuzu Banda in Nyasaland in 1959. Again, like Nkrumah in Ghana, Lumumba’s party, the MNC, contested local (provincial) council elections in 1959, while its leader was still in jail, and surprise, surprise, it too won a sweeping victory, as the electorate made no mistake in recognising why the leader had been jailed. In its main stronghold of Stanleyville, Lumumba’s party obtained no less than 90 percent of the votes. So, when in January 1960, the Belgian government invited all Congolese parties to a roundtable conference in Brussels to discuss political change and write a new constitution for the country, and the MNC refused to participate unless Lumumba was at its head, the Belgian government had no choice but to release Lumumba from prison and fly him to Brussels. It was at this conference that Lumumba showed his mettle - rising above the divisive politics that the Belgians wanted to promote among the various ethnic groupings, and uniting them on one central objective - independence. He managed to get a date agreed upon for independence – 30 June 1960. Lumumba returned from Brussels to contest the national elections that were held in May 1960: a mere one month to independence. I draw your attention again to the huge size of the Congo and the absence of anything in the country that resembled adequate infrastructure. This made it well-nigh impossible to campaign for elections on a national scale and of the 50 parties that put up candidates only two - Lumumba’s MNC and the Parti National du Progrès or PNP bothered to field candidates in provinces other than where their leadership originated from. Here is how the larger of the 50 parties that took part in the May 1960 general election performed: MNC-L [L for Lumumba] was strongest in Oriental Province (Eastern Congo) and was led by Patrice Lumumba. It won nearly a quarter of the seats in the lower house of the Congolese Parliament (33 out of 137) - thus garnering the highest number of seats for any single party. In the province of Léopoldville, Parti Solidaire Africain, or PSA (led by Antoine Gizenga) narrowly defeated the ABAKO party of Joseph Kasavubu). In Katanga province, Confédération des Associations Tribales de Katanga or CONAKAT, led by Moise Tshombé, won narrowly over its main rival, the Association Générale des Baluba de Katanga, or BALUBAKAT, led by Jason Sendwe. In Kivu, the Centre de Regroupement Africain, CEREA of Anicet Kashamura, won but didn't obtain a majority. MNC-L came second there. MNC-L also won in Kasaï, despite being obliged to fight against a splinter faction that had become MNC-K (under the leadership of Albert Kalonji, Joseph Iléo, and Cyrille Adoula). In the Eastern province, the MNC-L won a clear majority over the PNP, its only major adversary. Finally, in the province of Equateur, PUNA (led by Jean Bolikango and UNIMO (led by Justin Bomboko) were the victors. But as stated above, it was not Lumumba who, based on his performance at the elections, was first called upon by the Belgians to try to form a government. That honour went, instead, to the ABAKO leader, Joseph Kasavubu. But he failed, and it was then that Lumumba was asked to form a government. To the Belgians’ surprise, Lumumba succeeded in doing so. He clobbered together a coalition whose members were: UNC and COAKA (Kasaï), CEREA (Kivu), PSA (Léopoldville) and BALUBAKAT (Katanga). The parties in opposition to the coalition were PNP, MNC-K (Kasaï), ABAKO (Léopoldville), CONAKAT (Katanga), PUNA and UNIMO (Equateur), and RECO (Kivu). It was at this stage that Lumumba demonstrated how far-sighted he was. He convinced his coalition partners that the opposition parties should å≈not be ignored and he proposed that they should elect Joseph Kasavubu, the ABAKO leader, as President of the Republic. Lumumba’s coalition partners agreed, and the deal was announced on 24 June 1960. But unfortunately, Lumumba signed his own death warrant in appointing Kasavubu out of the best of intentions. In doing so, he implanted a poisonous Belgian wasp into his bosom. Lumumba’s action was acclaimed as an act of statesmanship and was endorsed by a vote of confidence in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. However, the Belgians began to use what would have been Lumumba’s political strengths against him. They now cultivated Kasavubu, filling his head with sweet words about how Lumumba was young and inexperienced, whereas Kasavubu was experienced and sagacious, as recognised in Brussels. He must not allow any ‘impulsive’ acts of the young Prime Minister to go unchallenged. And they backed their flattery with massive sums of money. Even more important, the Belgians planted into the office of the Prime Minister (Lumumba) as his principal aide, a former soldier called Joseph Mobutu. Mobutu had been recruited as an agent by the Belgians while attending the Exhibition of Brussels, following which he stayed on in Belgium as a student of ‘journalism’. With his military background, it would not have been difficult to teach him the tricks of espionage, instead. When Lumumba arrived in Belgium, straight from prison, to attend the constitutional conference, Mobutu befriended him - no doubt on Belgian instructions. Mobutu later joined the MNC and gained Lumumba’s confidence. At independence, he was well placed to be put in charge of defence at the Prime Minister’s office, given his seven years’ service in the Congolese army, the Force Publique. Prompted by his Belgian paymasters, Mobutu worked very closely with Kasavubu in secret to undermine the new Prime Minister. Now, on becoming Prime Minister, Lumumba had come very far indeed - and the distance between where he had sprung from and the complexities of political life marked by Belgian and American intrigues against him cannot be over-emphasised. Lumumba (his full name was Patrice Emery) was born on 2 July 1925, in the village of Onalua, in Kasai Province. His ethnic group, the Batetela, was small in comparison to such bigger groups in Kasai as the Baluba and the Bakongo. This gave him an advantage, for unlike politicians from big ethnic groups, no-one feared ‘domination’ from his side. He therefore found it easier to attract would-be political partners from other ethnic groups. Lumumba attended a Protestant mission school, after which he went to work in Kindu-Port-Empain, about 600km from Kisangani. There, he became active in the club of ‘educated Africans’, whom the Belgians called the ‘évolués’. He began to write essays and poems for Congolese journals. Next, Lumumba moved to Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) to work as a postal clerk and went on to become an accountant in the post office in Stanleyville (now Kisangani). There he continued to contribute to the Congolese press. In 1955 Lumumba became regional president of an all-Congolese trade union of government employees. This union, unlike other unions in the country, was not affiliated to any Belgian trade union. He also became active in the Belgian Liberal Party in the Congo. In 1956, Lumumba was invited with others to make a study tour of Belgium under the auspices of the Minister of Colonies. On his return, he was arrested on a charge of embezzlement from the post office. He was convicted and condemned to 12 months' imprisonment and a fine. It was shortly after Lumumba got out of prison that he became really active in politics. In October 1958, he founded the Congolese National Movement, NMC. Two months later, in December 1958, he travelled to Accra, Ghana, to attend the first All-African People's Conference. I was working in the newsroom of Radio Ghana at the time and was posted to Accra airport, to meet delegates to the conference, who were arriving at all sorts of odd hours. I remember Lumumba because of his goatee beard and his glasses, which gave him the look of an intellectual. My French was not up to scratch, but with the help of an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I was able to talk to him for a while before he was whisked away by an official car. He expressed his happiness to be in Accra, to seek inspiration from Ghana, the first British colony to achieve independence, and to exchange ideas with other freedom fighters. Lumumba and other French-speaking delegates did not get much of a look-in at the plenary conference, as far as the Ghanaian public was concerned, because people generally don’t react well to translated speeches, which take twice the time to make a speech in a language that is understood. But I also think that delegates like Lumumba, who came from repressive colonial regimes, were protected from the press as they could be penalized on their return home if they made any statements that did not please their colonial masters. The star of the conference was Tom Mboya of Kenya, who made a great impression with his command of the English language. ‘In 1885, the Europeans came and carried out a “scramble for Africa”,’ Mboya said. ‘We are now telling them to scram from Africa!’ This statement of Mboya’s was quoted widely around the world. Within a few years, he was Dead - struck down by an assassin. The All-African People’s Conference of December 1958 was notable not for the speeches made or the resolutions passed, but for the personal contacts that were made behind the scenes. The conference was the brain-child of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s Advisor on African Affairs, George Padmore. Now, Padmore was a most experienced operator in international politics, having been in charge of the Comintern’s section that dealt with African and black trade union matters, in the 1930s. He was a most intelligent and courageous operator: basing himself in Russia, Hamburg, and Finland, he befriended sailors of all colours, and was thus able to smuggle revolutionary literature - and personal messages - to anti-colonial politicians in Africa and all over the world where contacts with communist organisations were illegal. He also made several visits, incognito to African countries, including Ghana or the Gold Coast, as it was before it gained its independence. Padmore’s devotion to the black cause was so strong that when Josef Stalin ordered him to tone down his attacks on Britain, France, and other European colonialists, with whom Stalin had struck an alliance, during the Second World War, Padmore resigned from the Comintern. This was the most dangerous thing to do because Josef Stalin did not brook opposition. Padmore knew that he could be chased around and murdered - like Leon Trotsky. Indeed, the Kremlin tried to smear Padmore, claiming falsely that he had embezzled funds, but he defended himself effectively. He ended up in London where he set up as a writer of books and campaigner on anti-colonial issues. In London, Padmore became the mentor of many young African students who were later to achieve fame in the independence movements of their countries later. It was he who met Kwame Nkrumah when Nkrumah arrived in London as a student from the USA in May 1945. A strong bond of friendship grew between them and together, they organised the most famous Pan-African Conference of all – that at Manchester in October 1945. Nkrumah returned to Ghana in 1947 and organised the Convention People’s Party (CPP), with which he fought for and won independence for Ghana on 6 March 1957. In his Independence Day speech at the New Polo Ground in Accra, Nkrumah told the whole world that ‘The Independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the whole African continent.’ He indicated his willingness to put this idea into practice by inviting George Padmore to come to Accra to be Nkrumah’s advisor on African affairs. Padmore needed no second invitation: he saw an opportunity not only to work with a personal friend but also, to implement the ideas on pan-African unity and African independence to which he had devoted his life. Within a few months of arriving in Accra, Padmore had organised a ‘Conference of Independent African States’ there in April 1958. Its purpose was to link the independent African states in Africa, so that they could adopt common positions in world affairs, especially at the United Nations. Padmore followed that up by organising an ‘All-African People’s Conference’ in December of 1958. Lumumba was there and Padmore took him to meet Nkrumah. Lumumba was assured of Ghana’s full support from then on. He was made a member of the permanent organisation of the conference and stayed in touch with Ghana from then on. One historian has observed that after the conference, Lumumba’s ‘outlook and terminology, inspired by pan-African goals, now took on the tenor of militant nationalism.’ George Padmore established links in Paris, Brussels and Congo-Brazzaville, through which funds and political advice could be secretly transmitted to Lumumba and other Congolese politicians, when necessary. In late 1959, the Belgian government embarked on a programme intended to lead, ‘in five years’ to independence. The programme started with the local elections mentioned earlier (which were held in December 1959.) Lumumba and other Congolese leaders saw the Belgian programme as a scheme to install puppets before independence and at first announced a boycott of the elections. The Belgian authorities responded with repression and sought to ban the meetings of Congolese parties. On 30 October 1959, the Belgians tried to disperse a rally held by Lumumba’s MNC in Stanleyville. Thirty people were killed. Lumumba was arrested and imprisoned for ‘inciting a riot’. More clashes occurred around the country, and it was then that the Belgians, in an attempt to defuse the situation, organised an all-party ‘roundtable’ constitutional conference in Brussels. All the parties accepted the invitation to go to Brussels. But the MNC refused to participate without Lumumba. The Belgians thereupon released Lumumba and flew him in triumph to Brussels. At the conference, he observed that the Belgians were trying their old trick of ‘divide and rule’ by playing on the ethnic rivalries of the Congolese delegates. Lumumba outflanked the Belgians by getting the delegates to focus on a date for independence. Eventually, a date was agreed upon: 30 June 1960. National elections were to be held in May. As we have seen, not only did the MNC come first in the country, but also, it reached out to other parties, and Lumumba eventually emerged as Prime Minister. Lumumba was able to hold his own against the maneuvers of the Belgians at this time, because although Padmore had passed away in September 1959, he was receiving constant counselling from Dr Kwame Nkrumah in Accra. Indeed, some other Congolese politicians who would normally not have given him the time of day, were ushered his way by mutual friends in Accra. But when independence dawned in the Congo on 30 June 1960 it was doomed from the start. The independence constitution was drawn up largely by Belgian academics and officials without too much participation of the Congolese politicians present. The discussions were often abstruse and largely above the heads of the Congolese, none of whom had ever taken part in such an exercise before. So one-sided was the exercise that six Congolese students in Brussels held a demonstration in protest against ‘a constitution being written for Congo without Congolese participation.’ The Belgians dismissed them as trouble-makers. The document that emerged was a very complex text, and yet, it was made even more unwieldy by being released in two parts - one part in January 1960, and the second part in May 1960 - just one month before Independence. Belgian incompetence was written all over it: in some parts, the Congo was regarded as a centralised unitary state; in others, it was treated as a federal entity. These provisions were veritable booby-traps that were later fought over to determine who would wield ultimate control over the country’s finances and natural resources. The confusion in the document provided the kernel of the idea that the CONAKAT leader, Moise Tshombé, later developed - with Belgian advice - into the full-scale secession of his home province of Katanga shortly after independence. Nevertheless, Belgium, under the delusion that it was magnanimously atoning for the brutality it had unleashed on the Congolese people in the past, was full of self-congratulation. On the day of independence itself, the Belgian monarch, King, Baudoin, dressed in majestic finery, made an insensitive, self-congratulatory speech to the assembly of Congolese politicians and foreign guests assembled in the National Assembly. The Belgians in charge of the ceremony had not made any provision for the Prime Minister and leader of the country, Patrice Lumumba, to address the gathering. But Lumumba got up and spoke all the same: ‘Men and women of the Congo, Victorious fighters for independence who are today victorious, I greet you in the name of the Congolese Government. All of you, my friends, who have fought tirelessly at our sides, I ask you to make this June 30, 1960, an illustrious date that you will keep indelibly engraved in your hearts, a date of the significance of you will teach to your children so that they will make known to their sons and to their grandchildren, the glorious history of our fight for liberty… ‘No Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was by fighting that our independence has been won; [applause], it was not given to us but won in a day-to-day fight, an ardent and idealistic fight, a fight in which we were spared neither privation nor suffering, and for which we gave our strength and our blood. ‘We are proud of this struggle of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force. ‘That was our fate for eighty years of a colonial regime; our wounds are too fresh and too painful still for us to drive them from our memory. We have known harassing work, exacted in exchange for salaries that did not permit us to eat enough to drive away hunger, clothe ourselves, house ourselves decently, or raise our children as creatures dear to us. ‘We have known sarcasm, insults, blows that we endured morning, noon, and evening, because we are Negroes. Who will forget that to a black person, "tu”, was certainly said, not as to a friend, but because the more respectful "vous” was reserved for whites alone?’ He recalled: ‘We have seen our lands seized in the name of allegedly legal laws, which in fact recognized only that might is right. We have seen that the law was not the same for a white and for a black; accommodating for the first, cruel and inhuman for the other. ‘We have witnessed atrocious sufferings of those condemned for their political opinions or religious beliefs; exiled in their own country, their fate truly worse than death itself. We have seen in the towns, magnificent houses for the whites and crumbling shanties for the blacks. A black person was not admitted in the cinema, in the restaurants, in the stores of the Europeans; a black travelling on a boat was relegated to the holds, under the feet of the whites, who stayed up in their luxury cabins.’ Lumumba further demanded: ‘Who will ever forget the massacres where so many of our brothers perished, the cells into which those who refused to submit to a regime of oppression and exploitation were thrown [applause]? ‘All that, my brothers, we have endured. ‘But we, whom the vote of your elected representatives have given the right to direct our dear country, we who have suffered in our body and in our heart from colonial oppression, we tell you very loud, all that is henceforth ended. ‘The Republic of the Congo has been proclaimed, and our country is now in the hands of its own children. Together, my brothers, and my sisters, we are going to begin a new struggle, a sublime struggle, which will lead our country to peace, prosperity, and greatness. Together, we are going to show the world what the black man can do when he works in freedom, and we are going to make of the Congo the centre of the sun's radiance for all of Africa.’ (Lumumba added): ‘We are going to put an end to the suppression of free thought and see to it that all our citizens enjoy to the full the fundamental liberties foreseen in the Declaration of the Rights of Man [applause]. We are going to do away with all discrimination of every variety and assure for each and all, the position to which human dignity, work, and dedication entitles him…’ Then gesturing dramatically towards the assembly of Belgian dignitaries, each turned out in the fullest ceremonial plumage, Lumumba declared: ‘We are no longer your macaques [monkeys]!’ His electrifying speech was greeted with prolonged standing applause. When news of the fiery Lumumba speech spread through Leopoldville, a sense of euphoria enveloped the city. One man, in a picture I remember from the pages of Drum Magazine, was photographed lying prostrate in front of Lumumba’s car, arms spread out in a gesture that symbolically stated: ‘Drive over me if you like, My Leader! If I die today, I am satisfied enough to do so gladly!’ It was also reported that another Congolese, filled with pride, jumped the line of troops guarding King Baudoin at a public ceremony, removed the King’s ceremonial sword, and ran away with it into the crowd. But in the barracks of the Congolese army, the ‘Force Publique’, reality took a different turn altogether. The commander of the Force, Gen. Emile Janssens, felt obliged to make a speech to his assembled troops. He fatuously announced that the much-touted ‘independence’ would have no immediate effect on life in the Force Publique. The situation ‘après [after] l’independence', he very kindly explained, was precisely the same as ‘Avant [before] l’independance’. Contrary to reports they had heard, Janssens told the troops, ‘no African officers were to be commissioned in the near future’. Thus this insensitive officer shattered, with a few sentences, all the dreams that the Congolese soldiers had woven in their minds about life in an independent Congo. Their increased pay, their officers’ pips, the cars, the bungalows they had dreamt about - all vanished with the general’s words. Within hours, the troops had mutinied. Units brought in to restore order joined the mutineers, attacked their white officers, and turned on the officers' families, raping some of the women. Gangs of armed, uniformed troops looted shops, and indiscriminately beat and terrorized Europeans in the streets. Léopoldville's European population fled en masse across the river to the relative safety of Brazzaville. The mutiny spread to the interior of the country and non-African inhabitants found themselves under siege. Belgium now faced the task of evacuating its nationals under fire. It flew commandos in from Europe and secured the country’s major airfields while bringing in additional reinforcements by sea. Belgian forces in the Congo quickly swelled from an initial 3,800 to well over 10,000. To Prime Minister Lumumba and the Congolese army, this looked more like a colonialist coup than a rescue mission. Fire-fights broke out between Belgian units and Congolese soldiers, as Lumumba urged his people to resist all moves by the Belgian troops. Meanwhile, he appealed to independent African countries to send troops to help the Congolese army restore order so that the Belgian troops could be expelled from the Congo. Ghana’s President, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah was one of the first to respond to Lumumba’s appeal. The African group at the UN agreed with Nkrumah that Belgium was using the mutiny as an excuse to re-impose colonial rule on the Congo. So they asked the United Nations to order Belgium to withdraw its troops forthwith and replace them with UN troops. The UN procrastinated, as is usual with it. In the meantime, Lumumba asked Nkrumah directly for bilateral assistance. Within one week, Ghana was able to dispatch 1,193 troops to the Congo equipped with 156 military trucks and 160 tons of stores. The Ghanaian troops were mostly flown to the Congo by British Royal Air Force planes. (See W. Scott Thompson: Ghana’s Foreign Policy 1957-66 - Princeton University Press 1969). In addition, Ghana sent engineers, doctors and nurses, technicians, and artisans of all types to the Congo, some of them flying in by Egyptian planes, while others went by Ghana Airways aircraft, piloted by Ghanaians. The Congolese could hardly believe their eyes: at independence, the Congo had only six or so university graduates, and to see Africans piloting planes was mind-blowing to those who saw them. The Ghanaian troops in the Congo, on the other hand, did not always get a warm welcome from the Congolese, for a lot of their officers were white - three years after Ghana’s independence. Ghana’s chief of the defence staff was himself a British officer called General H. T. Alexander. He lacked the imagination - or confidence - to reconstitute the Ghanaian units that went to the Congo so that they would be officered by Ghanaians. The Congolese could not quite get their heads around the fact that if they were fighting against white Belgians, Ghana should come to their assistance with troops led by white officers. Belgian propaganda claimed that the white officers were Russian communists. To them, all the whites they knew - Belgians - were racist devils, and they could not understand that in Ghana, whites took orders from a black government. Thus misunderstanding was costly to Ghana - in one incident at Port Francqui, Ghanaian troops came under a surprise attack by Congolese soldiers and over two scores lost their lives. As a news editor at the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, I was following all these events carefully and tried to understand what was going on in the Congo, so as to broadcast bulletins to the people of Ghana that would make them understand the situation. One day, in September 1960, Radio Ghana’s monitoring section came up with a news item that was utterly shocking: President Joseph Kasavubu had announced over Radio Leopoldville that he had dismissed the Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba. Kasavubu said that he, as President, had used powers given to him under the Congolese constitution (the ‘Loi Fondamentale’) to dismiss Lumumba as Prime Minister. Very soon, we got another flash: in retaliation, Lumumba had also sacked Kasavubu. Lumumba took the precaution of immediately asking the Congolese Senate to give him a vote of confidence over what he had done. Despite a huge outlay of secret cash payments made by the Belgians and the Americans to influence the Congolese Parliamentarians to take Kasavubu‘s side, it was Lumumba’s dismissal of Kasavubu that the Senators endorsed. Later, the lower House of Parliament also supported Lumumba with a vote of confidence. Meanwhile, the newspapers of the world, unable to decipher Congolese constitutional matters and distinguish between who had acted legally and who had acted illegally, had a field day running this mocking headline: ‘Kasavubu sacks Lumumba! Lumumba sacks Kasavubu!’ Lumumba made a very eloquent speech asking the Congolese Parliament to dismiss Kasavubu. The speech was probably the last one he made in public that was fully recorded. Our monitoring station transcribed it for us and I ran the transcript of it almost in full in our news bulletins. Patrice Lumumba said: ‘It was we who made Kasavubu what he is. As you well know, he has no majority in this Parliament. He tried to form a government and failed. Yet, out of our desire for national unity, we generously offered him the highest office in the land - the presidency - instead of giving it to someone from our own side, the majority side.’ Lumumba continued: ‘We made that sacrifice in order that we could achieve the unity without which we cannot build our new nation in a stable atmosphere. And now he turns round to say that he has sacked, me, the leader of the majority! It was by my hand - this hand - that he was appointed President. It is an insult to our people, who voted us into this Parliament. How can a person who commands a minority of votes in this House sack the one who has the majority? It is not done anywhere that there is a parliamentary system. It cannot be done in Belgium! Why must it be allowed to be done here?’ The vote of confidence Lumumba got surprised Kasavubu, whose strategy for neutralising Lumumba was plotted from Brussels and Washington. The Belgians and the Americans were left with egg on their faces, for they had given money to Kasavubu to bribe many of the MPs! The MPs had taken the money, and yet voted against Kasavubu! The Americans and the Belgians were outraged. But with the full weight of the CIA now in support of Belgium’s objective of throwing out Lumumba, his was a lost cause. In the midst of the confusion following the mutual sackings, Sergeant (promoted Colonel) Joseph-Desire Mobutu, staged a coup d’etat on 14 September 1960 against both Kasavubu and Lumumba. Or so he claimed. (Mobutu, remember, had been a Belgian secret agent of long-standing but also doubled for the CIA. The Belgians then planted him in Lumumba's office as Lumumba’s army chief of staff, and though Lumumba made sure that he also appointed an army commander who was loyal to him, General Victor Lundula, this Lundula was barely literate and no match to the far more literate and ever-scheming Mobutu. When Mobutu struck, his pretext was that he wanted to ‘bring peace’ to the country and save it from the ‘squabbling politicians’. This was classic coup-makers language. Time Magazine ran a hilarious account of Mobutu’s coup in its issue of 26 September 1960 (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,897597,00.html) In his book, ‘The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba’, the Belgian writer, Ludo De Witte, gives us a detailed description of what was happening in Congo at the time. ‘Belgian military chiefs’, De Witte wrote, ‘made nightly visits to Mobutu and President Kasavubu to plot Lumumba's downfall.’ A Belgian officer, Colonel Louis Maliere, ‘spoke [to De Witte] of the millions of francs he brought over [from Belgium] for this purpose.’ The Belgian plot to kill Lumumba was nicknamed ‘Operation Barracuda’ and was run by the Belgian Minister for African Affairs, Count d'Aspremont Lynden, himself. As mentioned earlier, the CIA was also fully on board. This is how the informative magazine, US News and World Report, described one aspect of the CIA effort. The head of the CIA, Mr. Allen Dulles, cabled the CIA station chief in Leopoldville that: ‘In high quarters here, it is the clear-cut conclusion that if [Lumumba] continues to hold high office, the inevitable result will [be] disastrous consequences…for the interests of the free world generally. Consequently, we conclude that his removal must be an urgent and prime objective.’ A later report in the same paper was even more detailed: ‘It was the height of the Cold War when Sidney Gottlieb arrived in Congo in September 1960. The CIA man was toting a vial of poison. His target: the toothbrush of Patrice Lumumba, Congo's charismatic first prime minister, who was also feared to be a rabid Communist. As it happened, Lumumba was toppled in a military coup just days before Gottlieb turned up with his poison. The plot was abandoned, the lethal potion dumped in the Congo River.’ When Lumumba finally was killed, in January 1961, no one was surprised when fingers started pointing at the CIA. A Senate investigation of CIA assassinations 14 years later found no proof that the agency was behind the hit, but suspicions linger. But all the evidence suggests that Belgium was the mastermind. According to ‘The Assassination of Lumumba’, Belgian operatives directed and carried out the murder, and even helped to dispose of the body. Belgium finally got its chance to eliminate Lumumba after Mobutu’s troops arrested him in December 1960. Belgian officials engineered his transfer by air to the breakaway province of Katanga, which was under Belgian control. De Witte reveals a telegram from d'Aspremont Lynden, that Lumumba be sent to Katanga. Anyone who knew the place knew that was a death sentence. Does that mean the CIA didn't play a role? Declassified US cables from the year preceding the assassination show that Lumumba clearly scared the daylights out of the Eisenhower administration. When Lumumba arrived in Katanga, on 17 January, accompanied by several Belgians, he was bleeding from a severe beating. Later that evening, Lumumba was killed by a firing squad commanded by a Belgian officer. A week earlier, Lumumba had written to his wife, ‘I prefer to die with my head unbowed, my faith unshakable, and with a profound trust in the destiny of my country.’ The next step was to destroy the evidence. Four days later, Belgian police commissioner Gerard Soete and his brother cut up the body with a hacksaw and dissolved it in sulphuric acid. In an interview on Belgian television, Soete displayed a bullet and two teeth he said were saved from Lumumba's body. A Belgian official who helped engineer Lumumba's transfer to Katanga told De Witte that he kept CIA station chief Lawrence Devlin fully informed of the plan. ‘The Americans were informed of the transfer because they actively discussed this thing for weeks,’ says De Witte. Final proof of the CIA’s hand in the murder is given by the fact that when the CIA officer in Elizabethville saw that Lumumba had been delivered safely into the hands of his Katangese enemies, he wrote to his counterpart in Leopoldville: ‘Thanks for Patrice. If we had known he was coming, we would have baked a snake.’ Whatever the racist sentiments behind the message, its intent was clear: congratulations for bringing him to us to do as we please with.