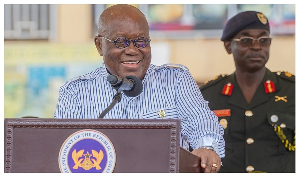

President of Ghana, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo

President of Ghana, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo

The Presidency and the Supreme Court

The President

The President is often regarded as "father for all," a phrase reflecting the expectation of leadership that is nurturing and protective. This metaphor emphasises that a leader should govern not solely as an authority but as a unifier who cares for the nation like a family, with guidance, protection, and wisdom as key attributes. These traits should overshadow power dynamics, reducing conflicts that strain national unity.

President Akufo-Addo embraces this title of “father for all.” However, certain moments in the hung parliament presented opportunities to embody this role, which the presidency seems to have missed. In my view, I believe situations such as the choice of Speaker, circumstances leading to the passing of the E-Levy, and the stay of the Speaker’s vacant seats declarations were moments that he could have seized for building bridges across the aisle, fostering long-term peace and cohesion. One would assume that a “father for all” will urge for conciliation just as a sagacious father will in a family deadlocked by division. He would act as a peacemaker, calming tensions rather than inflaming them, uniting instead of entrenching divides.

I reflect and wonder, did actions such as bringing in the military on the day of the Speaker’s election, the stance taken during the passage of the E-Levy and other potentially divisive actions lay the foundation for the current political standoff, which has drawn the Supreme Court into a fragile situation with serious ramifications for Parliament and social cohesion, depending on the manner of adjudication and outcome? Is the worst yet to come, or are these “necessary disruptions” that will usher in a new phase of democracy in our nation? Or is it the stark reality that, over the years, "practical wisdom" has been sidelined in handling sensitive or potentially divisive matters in our nation's governance because our leaders have become more partisan than Ghanaian?

Well, if it is the latter, then history offers the Presidency valuable lessons. For instance, “The Compromise of 1790 (U.S.A.)”, a political agreement between Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, and Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State, with support from James Madison that resolved a key disagreement in the newly formed United States over two major issues.

Also, “The Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)”, a moment where mutual concessions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union led by President John F. Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushche prevented nuclear war. More recently, President Obama, using a strategic blend of policy compromises and personal outreach to secure the necessary votes for the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), and even playing a round of golf with Speaker John Boehner in a symbolic gesture to foster bipartisanship amid political gridlock on issues like the national debt ceiling and budget cuts. In all of these, legalism, displays of military might, and power dynamics were set aside for compromise, negotiation, and pragmatism.

The Supreme Court (SC)

The Supreme Court, often seen as Ghana’s “last bastion of hope,” is supposed to provide final, impartial resolutions when all other avenues for justice seem exhausted. Its power to check lower court decisions and the legislature’s actions underscores its role as a guardian of justice and fundamental rights.

While this responsibility is widely recognised, some recent decisions have sparked public discourse on how the court can best continue its tradition as an ‘embodiment of wisdom’ and ‘moral authority.” For example, the reasons adduced for the recent stay of execution by the SC on the Speaker’s vacant seats declaration, and the perceived gaps in judicial attention to the case involving Santrokofi, Akpafu, Lipke and Lolobi (SALL)—which have been without representation for almost four years risk creating an unfavourable perception about the SC.

It is tempting to reason that if the potential loss of representation for certain constituencies, along with the potential loss of emoluments and ex gratia payments for affected MPs, should the seats be declared vacant, are urgent matters, then what about the people of SALL who have been without representation for so long? Another pending case is the anti-LGBTQ+ case, yet to be ruled upon.

As a Ghanaian proverb goes, “Sɛ wotwe adeɛ afri soro na ɛmma a na biriibi kura mu,” meaning “If something does not fall from above, there must be something holding it back.” Perhaps the timing of rulings on these matters is influenced by complex factors. Considering recent Afrobarometer survey reports on waning trust in the courts, updates on these high-profile cases could help manage public expectations, reinforce transparency, and demonstrate the Court’s equal dedication to justice in all cases. This way, Lord Hewart’s words can ring true: “Justice must not only be done, but must also be seen to be done.”

We count on you as our “last bastion of hope.” The wisdom needed to safeguard justice is yours to wield. May you consider Socrates’ trial and the role of the Athenian Jury, or Pakistan’s judicial crisis of 2007 under Chief Justice Chaudhry in your decisions. Your role is paramount in ensuring that “practical wisdom” remains a virtue of Ghana’s body politic and not desert us.

Recognise that “observers are worried.”