If you are of a certain age and know Accra a bit, you must know Shangri-La. A cute, low-rise, hotel along the northern stretch of the Liberation road, and on the doorstep of what later became the Israeli-built Tetteh Quarshie Interchange and, a few years later, the Accra Mall. If you are middle-class enough, you may even remember the legendary “pizza by the pool”.

In its heyday, Shangri-La, nestled daintily in the city’s swanky airport district and touching the northernmost edge of its old colonial charm amidst the stables of the Polo Club, was indeed the classy choice of the aspirational set.

But by 2011, it was being dissed by this same crowd and described as worthy of bulldozing. It will linger on for a few more years before its demolition.

Following its demolition more than a decade ago, the land has been lying fallow. Many Accra residents who ply that stretch of Liberation Road must have wondered every time they see the bus-stop sign why such a disheveled patch of land could be left where it is for so long considering all the plush structures in the surrounding area.

The more inquisitive would have noticed that Shangri-La is not the only abandoned hotel in the neighborhood. Nearby Granada has also been in a state of disrepair for at least the same length of time.

Few, however, would be aware of this intriguing story of the land on which both The Granada and the Shangri-La are located.

In the years when the fear of global epidemics made airports and seaports high-risk portals into towns, it was customary for harsh quarantine measures to be imposed at these entry points just as we saw at airports around the world in the early heady days of the COVID-19.

A bit of this history lives on in the discomfort that air travelers to Ghana feel when they have to endure the smell of insecticides designed to kill off yellow-fever carrying mosquitos before planes bound for the country take off. In ancient times, things were far less sanguine. Lacking our modern vaccines and whatnots, some towns would even sink ships and murder travelers docking at their ports if they suspected any vessels of carrying infections.

Anyway, the fear of disease spreading by air transport led to the creation of so-called "anti-amaryl aerodromes", which are facilities for handling aeroplanes suspected to have originated from or transited disease-endemic ports. These special aerodromes were isolated from human settlements to the extent possible.

In 1936, the British colonial government decided to establish an anti-amaryl aerodrome in Accra and compulsorily acquired a large tract of land from the La Stool to do same. By 1944, however, the whole concept of anti-amaryl hangars had fallen out of favour. The International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation would then proceed to more or less render it redundant.

Over the years, the state has found a way to parcel lands such as the one hosting the Granada, the Polo Club, and the Shangri-La and hand them over to private businesses under rather opaque circumstances.

One such beneficiary was Armen Kassardjian, the developer of the Shangri-La hotel in Ghana.

The Kassardjians are a legendary Ghanaian-Lebanese family of Armenian origin. When the patriarch of this storied family, Askor, first arrived in the colonial Gold Coast in the 1940s, he made what became Northern Ghana his base, soon becoming a construction magnate.

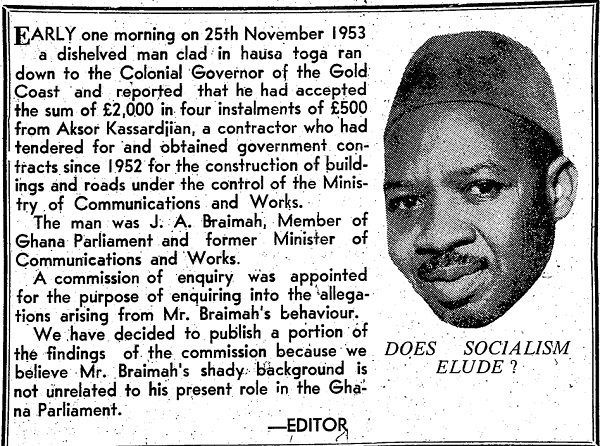

The elder Kassardjian would soon become embroiled in some of the titilating scandals of pre-Independence Ghana, especially the J.A. Braimah “bribes for road contracts” scandal.

Yet, the long history of his contributions to the built environment in Tamale, Navrongo, and elsewhere in the South is of such sheer pedigree that a few years ago, Ghana’s national archives decided to stage an exhibition of his life.

Other Kassardjians own various ventures across the country such as the Hillburi resort in Aburi, elevator engineering firms, and agro-commodities trading houses.

Whilst Armen Kassardjian has treaded the same entrepreneurial paths of his mighty clan forebears, in the matter of Shangri-La, the record is rather mixed.

In 1991, fresh off settling an economic sabotage indictment by the Office of Special Prosecutor with the PNDC government, via the National Public Tribunal, Mr. Kassardjian began to contemplate additional luxury real estate investments.

Long before the likes of Villagio became a commonplace sight, he had his eyes on the future of upper middle-class living in modern residential complexes. His Palm Royale Apartments were poised to set a glamorous new trend.

Unfortunately, Ghana’s weak credit market tampered most of his dreams. Then one day he heard about the private-sector arm of the World Bank. Most business folks know of the Washington DC – based organisation only as a lender to governments. Of course, it also gives billions to entrepreneurs of the right calibre or endurance. Mr. Kassardjian was determined to get some of the nice dollars, whatever it took.

In 1994, and also in 1995, he succeeded in extracting a cool total of $1.3 million from the Bretton Woods institution, most of which were earmarked for Shangri-La’s refurbishment into a leading high-end facility in Accra.

It is not clear what the hotelier had been told by whoever briefed him about approaching the World Bank. But, somehow, he didn’t seem to have entered into the borrowing transaction with an intent to repay. Because as early as 1996, he was already behind on his payments. In 1997, he defaulted. Between 1997 and 2000, efforts to restructure the facility went nowhere.

So bizarre was the situation that upon some worrying tip-offs, a major investigation into the Bank staff that worked on the loan facility was launched. The lead investment officer, a young Ghanaian professional, was subsequently fired on suspicion of compromise. The matter will go before a specialised tribunal which affirmed the firing in 2006.

Meanwhile, the World Bank was fighting Shangri-La in the local courts in a series of cases that travelled all the way to the Supreme Court between 2003 and 2005. Despite its legal victories, the World Bank struggled to enforce the judgments and recover its losses.

In these circumstances, Shangri-La’s investment reputation was dented beyond repair. Finding money for the level of refurbishments needed to keep up with Accra’s frothy high-end accommodation market proved impossible.

A decade ago, Mr. Kassardjian and his business partners thought they had finally cracked it. A major announcement was made. In light of the failed STX deal to build ten thousand houses for Ghana’s security personnel, Korean investors were said to be keen on making another try. A $200 million project to build nearly 300 apartments on the Shangri-La site, glamorously christened Skyville, was said to be in the offing.

Curiously, an eerily identical project, costing $250 million, was also announced a few months ahead of Skyville this one involving a Singaporean company and the Chinese hotel giant that uses the “Shangri-La” brand worldwide (I will refer to it as “Shangri-La Global” going forward to avoid confusion with the Ghanaian copy that bore its name). In addition to the customary luxury apartments and a freshly built world-class Shangri-La hotel, a mall and office complex were also in the picture. 2019 was set as the timeline for launch.

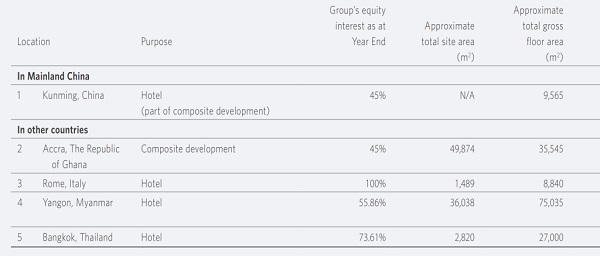

Shangri-La Global appeared to have settled on the Ghana entry, acquired the land, and then sold 55% of the opportunity for $15.2 million to Perennial, the Singaporean investor attracted to the deal by Wilmar, another Singaporean firm with extensive African holdings that is part of the same Kuok Group that owns Shangri-La Global. In fact, Perennial’s special purpose vehicle in Ghana shares senior management with Wilmar Ghana.

Ahead of the originally scheduled launch date of 2019, Shangri-La Global and Perennial resumed their engagement with the investment authorities in Ghana. The Korean-Ghanaian project had by then completely disappeared from the limelight.

But 2019 came and went without any launch. Perennial shifted launch date to 2023. The project’s name was now given as Accra Integrated Development.

At Shangri-La Global, it continues to remain under “concept planning”.

The latest news is that Shangri-La Global, after a decade of trying, is on the verge of abandoning the effort. Our sources say that it is trying hard to sell off the remaining 45% equity it holds in the project. Perennial’s intentions are opaque as at now but, clearly, with Shangri-La giving up, the prospects for the project in its current design have dimmed.

As for Skyville, the rival project explicitly involving the Kassardjians, it never seemed to have evolved beyond aggressive marketing in 2016. Backed by glitzy architectural drawings.

Its hopeful sponsors continue to hire ambitious architects to keep the dream alive.

For now, only rugged fences shielding the empty, weedy, patches remind the observer of the currency of the dreams that lurk behind. From 500 km above us, satellites reveal the desolate patches, showing that both the Skyville site and the next-door Wilmar – Shangri-La grounds remain stubbornly fallow.

Next time you see another abandoned building or site in a prime area in Accra, you can rest assured that some twisted saga lays underneath.