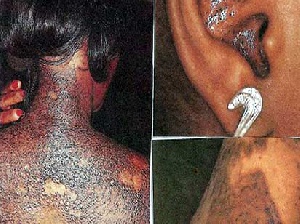

Skin disorders as a result of bleaching.

Skin disorders as a result of bleaching.

“The size of your dreams must always exceed your current capacity to achieve them. If your dreams do not scare you, they are not big enough” (Ellen Johnson Sirleaf)

PROF. AGYEMAN BADU AKOSA ON BLEACHING

“The size of the problem in Ghana is enormous and it cuts across age groups, sex and class groupings…Every identifiable group of persons are represented in the guilty group. Professional people including lawyers, doctors, nurses, teachers, etc., business persons, charismatic and non charismatic pastors or reverends, media people, traders, fishermen, chiefs and the worst offenders, queenmothers.

“In the latter group particularly in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, if you are nominated and installed as a queenmother you must lighten your skin before the enstoolment. It brightens you up they say, in much the same way as putting on the light in a room.”

(Statement taken from Jemima Pierre’s book “The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race”).

THE COLOR-LINE PROBLEM IN THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” (W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Souls of Black Folk”).

Just recently Nigerian actress Mercy Johnson, one of our favorite actresses from Africa reportedly made the following heart-wrenching statement:

“It is very true that when I was starting out in the movie industry, it was difficult to get roles because of my complexion. I faced that a lot and I tell people that my success is just grace. Somebody once told me that I am too dark but that is where the grace and favour of God comes in. Regardless of everything, most of the dark-skinned actresses that are my contemporaries made it.”

Though her reference point was Nigeria, the problem of internalized black inferiority complex and the attendant problem of skin-bleaching seem to cut across the black community.

Let us not deceive ourselves however, for blanching or bleaching is a problem for non-black peoples in such places as India, the United States, Japan, the Philippines, and Brazil.

The Japanese have the following sayings—“White skin covers the seven flaws” and “bihaku” (beautiful and white)—to signal the symbol of whiteness and beauty in Japanese society. Here is Professor Miho Sato of the Human Science Department, Waseda University (Nana Tsujimoto):

“…Japanese people have seen the color white as holy [shinseina] and mysterious [shinpiteki] for a long time…Experiencing globalization, a white face became not only a Japanese standard of beauty but also an international standard. White skin has been a symbol of beauty for Japanese women. Actually, that is why many Japanese women avoid getting tanned.”

In Jamaica black mothers bleach their children as young as one, all because of the persistent question of social prestige borne out of colorism and otherism! But our primary focus is on bleaching in Africa. In 2015 for instance, Lupita Amondi Nyong'o, an American-based Kenyan actress, shocked the world when she said she was told her skin was “too dark” for Kenyan television.

Creative, talented men and women have their natural gifts going to waste because discriminatory practices which have nothing to do with tapping into, nursing, or enhancing the fertile reservoirs of the natural aptitudes which these men and women possess, but rather the promotion of the most trivial of human perceptions—skin color.

But for the inspiration she took from world-famous South Sudanese model Alek Wek for instance, Lupia’s self-esteem would have been a drag on her professional career and confidence.

Nyong'o’s role as the mother of Uganda’s chess prodigy Phiona Mutesi in the biopic The “Queen of Katwe,” to name but one movie she has starred in, is just phenomenal (see also Tim Crothers’ “The Queen of Katwe: A Story of Life, Chess, and One Extraordinary Girl's Dream of Becoming a Grandmaster”).

Is it talent rather than skin color that matters? Then again, according to Tsujimoto, the proverb “white skin covers the seven flaws” means that “a fair-skinned women [sic] looks beautiful even if her features are not good.”

This statement unambiguously points to one of the major reasons many of our women bleach their skins in the first place—a primary example being the Nigerian-Cameroonian pop singer Dencia, who admitted in a 2014 interview that “white means pure” in connection with a skin-bleaching product, called “Whitenicious,” she has been promoting—although many African men also bleach their skins.

Some point the finger at Daddy Lumba, Apostle Kwadwo Safo, Bukom Banku, Rev. Owusu Bempa, and Lordina Mahama, President Mahama’s wife. However besides Dencia, other public Nigerians known for bleaching their skins include Tonto Dikeh, Pela Tonye Okiemute (male), Thelma O’khaz, and Susan Maxwell (see Yetunde Mercy Olumide’s book “The Vanishing Black African Woman: Volume One: A Compendium of the Global Skin-Lightening Practice” for an extensive coverage of the problem across Africa).

Here is Susan Maxwell (Olumide):

“Many people are of the opinion that light-skin ladies are more attractive, and everything they wear shows off better and that is why I am here to help people enhance their complexion. I used to be very dark; I never thought I could become as fair as I am. I did it because I want to practice what I preach. I want them to see me and be blown away, especially those who knew me when I was dark...If I wasn’t in this line of business, I probably wouldn’t have toned my skin at all. I don’t call it bleaching. I call it restoration.

“…Most of my clients are 18, and if they want to be white, I give them what they want. Black is beautiful, but I have no qualms with enhancing your complexion. 80% of Nigerian men want their women to be fair. They want a lady that draws attention to them. I’ve worked with many married women who complain of their men staring at fair women and they say to me:

“‘Susan, make me fair, I want to be attractive to my man!’ Some women have said their sons want them to visit their schools because they want to show off their fair mother…Black is beautiful but there is nothing wrong with enhancing your complexion.”

Some studies have it that at least 70% of Nigerian women confess to using one form of bleaching or whitening product to another. Like one of these author’s classmates used to say, even God likes what is fair and also loves whiteness.

Granted, Susan’s offers an excellent synopsis of the problem of skin-bleaching not only in Nigeria but across Africa.

But Olisa Adibua, one of Nigeria’s and Africa’s top media personalities has these harsh words for her:

“I think it is disgusting and horrible. I don’t believe most Nigerian men love women with fair skin…In fact, being natural is most preferable. Most women who bleach end up with darker knuckles and knees like it’s not part of their bodies. They also have a very horrible smell.”

This statement may sound misogynistic to a certain extent. While it is true that skin-bleaching may trigger all sorts of awful smell in women, what do we have to say about men who bleach? In other words is it possible for a man who also bleaches his skin, like a woman, to have a dreadful odor?

Elsewhere the romantic walls around Buju Banton’s love for light-skinned women, symbolized by romantic ballads such as “Love Me Browning,” came tumbling down when the general public and his fandom exposed his penchant for—or infatuation with—the fair sex.

He was subjected to public criticism, during which time he released “Love Black Woman” to assuage the rising tide of public angst. Ghanaian musicians will no doubt call “Love Me Browning” “Obibini Se Broni.”

Finally, LisaRaye McCoy’s anti-skin-bleaching/anti-whitening movie “Skinned,” a movie featuring Van Vicker, and Akosua Adoma Owusu’s short film “Me Broni Ba” are a must-see. Indeed, pigmentocracy and low self-esteem is a real problem across the world.

We shall return with Part 2, the concluding segment.