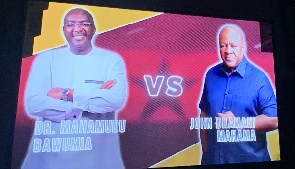

The 2024 elections will be between Mahama and Bawumia

The 2024 elections will be between Mahama and Bawumia

Yesterday on November 4, 2023, based on the routine political risk & political economy analysis done at IMANI, I wrote a short essay on the likely permutations of Ghana's ruling party primaries, which came off today. I pointed out that the favourite to win the elections, the Veep, will be denied a coronation, against the wishes of the party elites and gatekeepers, because he has lost some of his shine with the grassroots. Provisional results of the primaries are in, and with them an updated sense of how the 2024 elections are likely to pan out if nothing much changes dramatically.

1. No candidate in Ghana's history has gone on to win the general elections if s/he obtained less than 85% of the vote in internal primaries, except in 2000, which was a very special election (the country had never before seen a switch of power through the ballot).

2. No candidate has gone on to win the general elections if s/he had obtained less than 64% of the vote in the internal primaries.

3. The Veep's projected 61.5% victory in today's primaries was lower than the 68% victory he won during the Super-Delegate pre-primaries. This is consistent with the theory that the grassroots are less excited by him than are the elites.

4. The Veep's results are despite one of his main rivals dropping out of the race. It is very likely that his tally would have dropped to the low fifties if this rival had stayed because this rival's followers do not have a high cross-over with the followers of the runner-up in the just-ended primaries, an eccentric business man & MP.

5. The biggest risk to manage in the aftermath of the elections for the ruling NPP is the runner-up in the primaries seeking to undermine the Veep's candidacy in the general elections in any way. The rival who dropped out is already gearing up to run as an independent in 2024. He needs to win just 2% of the vote to ensure an automatic win for the Opposition. But this is a high bar. The runner-up, on the other hand, would easily win 10% plus of the national vote in the unlikely event that he goes independent due to his "Ross Perot" level of disruptive influence. The ruling party will move Heaven & Earth to prevent this.

6. Whilst the Veep's performance in the primaries and the government's falling out of favour due to the economic crisis works strongly in favour of the Opposition party, should none of the scenarios in point 5 occur, the ruling NPP still has a path to a narrow presidential victory (while losing their slim Parliamentary technical majority). This is due to a "Northern" and "Muslim" dynamic that the Veep is introducing to unsettle the electoral equilibrium in Ghana. If the Opposition fails to respond with their own "Akan heartland" dynamic, they risk a narrow defeat in the presidential polls.

For further explanation, the essay is below

Tomorrow (November 4, 2023), the man tipped to win the primaries of Ghana’s ruling party and succeed the country’s sitting President as the ruling party’s candidate in the 2024 elections shall NOT be coronated.

His non-coronation is a source of great anguish for party bosses who have done everything to make the ascendancy of the Vice President to the “flagbearer” position resemble a sweeping endorsement from all corners of Ghana’s oldest political party. Since the return to democracy in 1992, no candidate has won the presidential elections without a landslide victory during their party’s primaries.

For instance, the Opposition Leader, himself a former President and Vice President, garnered nearly 99% in the Opposition NDC’s primaries six months ago. The sitting President, in keeping with the same trend, scored nearly 95% in the 2014 primaries that blazed his way to the presidency.

On those occasions when a presidential candidate has won by less than 85% in their own party’s primaries (like in 2002 and 2006 during the NDC primaries; or in 2007 and 2010 during the NPP primaries), their chance of winning the subsequent national elections has been almost nil (the 2000 elections being a notable exception). It would seem from the record that carrying a party to a successful showing in Ghanaian general elections requires a candidate to mobilise a resounding and sweeping endorsement, a coronation, in essence.

The Magic Rise

The current Veep has had a charmed life in his political career. Plucked from relative obscurity, like other Veeps before him, from the technocratic halls of the Bank of Ghana to join the NPP presidential ticket a few months to the 2008 general election, he had everything to prove. Since then, the 60 year-old politician has earned his stripes by transforming himself into the ruling NPP’s most ardent champion of the party’s signature, slogan-heavy, political PR style.

His impeccable academic credentials and northern ethnic and Islamic religious heritage in a party dominated by Southern, mainly Akan, Christians combined to endow his rise with a certain kind of exotic fairy-tale flourish. His profile rose in the party so dramatically that at one point a coronation seemed inevitable as party bigshots lined up behind the narrative of his inevitability. And then Ghana’s economic down-spiral began, eventually landing in a catastrophic heap requiring an emergency IMF bailout and national insolvency.

The same credentials in economics that had catapulted the Veep in the eyes of the party’s elite gatekeepers during the party’s spell in opposition, and made him the most effective lampooner of the ruling government’s economic policies, have today also become his undoing. His lack of deep grounding in the ruling party is suddenly an issue again. The grassroots of the party are suddenly being asked by his rivals whether they get what all the fuss is about that Oxford economics degree and those majestic lectures that have defined his rise. Many, it would seem, are suddenly unsure about the grand narrative of the Veep’s specialness.

A Maverick party-pooper

Which is probably why the Veep’s most effective rival in the primaries is a maverick businessman and veteran ruling party parliamentarian who boasts of employing 7000 people despite never having bothered to complete his undergraduate degree in a suburban New York university.

The said rival’s shoot from the hip politics and eccentric campaign style of criticizing the record of the government even though this is an internal election has rattled party bosses who have been at pains to deny his accusations of their favoritism towards the Veep, whilst still needing to give as strong a hint as possible that failure to elect the first Muslim and Northerner as the NPP’s presidential candidate will seal the charge against the Party of being biased towards the predominantly Akan Christian South.

The Primacy of Identity Politics

All said and done, there will be no coronation tomorrow, Saturday, the 4th of November, 2023. The Veep is expected to cross the line in a comfortable lead but considerably below the threshold that super-successful candidates have scored in internal primaries ahead of victory at the national polls. What does this mean for his chances in the 2024 general election?

If the 2024 elections were to be fought primarily on policy performance, then, coupled with the less than complete mobilization of the ruling party’s base, as manifested by his expected result in tomorrow’s primaries, the opposition NDC would have won in a heartbeat. But like elections all over the world, policy is rarely the sole defining factor, and the issue of identity politics looms large.

If the Veep wins the primaries as predicted, the NPP’s historical strength in the southern and middle-belt Akan areas mean that he will have far more latitude in pressing identity-related issues in the Muslim majority areas and the geographical North of the country than the Opposition’s candidate, who is a Christian from the North. The reason is simply that the NDC has a somewhat fraught relationship with voters in the Akan heartland, urging serious circumspection about how they approach campaigning in the North and the Muslim-dominated “Zongos” for fear of alienating the highly populous Akan regions.

Because ethnic alliances and allegiances in Ghana usually radiate through the political parties to envelop the candidates, rather than the other way round (very different from the case in Kenya and Nigeria in that sense), the Veep is unlikely to lose many Akan and Christian voters regardless of the intensity of his campaign team’s overtures to the Islamic and Northern constituencies, which frees them to be more creative and adventurous.

The Opposition’s only hope of countering this new dynamic is to come up with their own dynamic to unsettle the Akan heartland of the ruling party. In a recent tweet, I consolidated one possible approach around the idea of an “Akan heartland vote-puller” being selected as the running mate to the Opposition Leader. Upon reflection, it is clear that more than that would be required in terms of effective messaging, and campaign machinery all-round, targeted at the fraying seams of the Akan meta-identity. Recall that the ruling party won the presidential race three years ago with a 500,000 vote margin, a significant gap that the Opposition must close before they can cross the line.

One controversial point is that the “Akan Heartland” refers less to all the Akan regions and more to those parts of the Akan-dominated geography with predictable voting patterns. Highly urbanized coastal towns like Cape Coast or Mankessim tend to swing with the national mood and are thus less susceptible to the kind of strategy discussed above.

It is true that the Opposition is extremely confident of winning the next elections. Their conviction comes from the belief that the Veep embodies a number of serious electoral risks. Some say that a sizeable number of evangelical Christians in the swing voters’ category might balk at voting for a Muslim (Ghana has never had a publicly-confessed Muslim as President). Others say that the Veep is so deeply entangled with the policy chaos of recent years that he will be ready fodder for scathing satirists when the campaign season start.

The religious question, as already hinted, can go either way. What the Veep loses from the evangelical community, he may gain from the devout Islamic community.

The policy charges are stronger. The Veep sold himself as an economic guru responsible for architecting a wholesale transformation of the country. The self-evident reality is that the country has declared bankruptcy and large portions of private wealth have been wiped away in the most intense economic crisis since 1983. Then there is a nascent IMF austerity program. As he himself wrote in 1998, IMF programs tend to create losers and winners, generating electoral consequences.

True, in recent years, the Veep has also positioned himself as a digital champion, and some allege that as the economy has tanked, this “tilt” has now become a hard pivot.

For most people, the digitalisation results are sound but modest. For hardcore policy people, like some of those who regularly read these pages, however, there is actually a lot to fault about the Veep’s handling of the so-called digitalisation agenda. Let us look at a few of the most prominent digitalisation flagships.

Digital Addressing

Ghana has spent millions of dollars on a pre-existing digital application reskinned into a national geotagging platform by the private app developer.

This is despite the said system merely drawing on open-source mapping solutions available at no cost from the primary geolocation platforms. It took years for the Veep and his team to realise this. Instead of a serious fix, he hastily announced to the country three years ago that Google has agreed to “upload” Ghana’s mapping system into its platform, when such a move would be completely pointless as Google already offers the Plus Codes system that duplicates the full set of functions ineffectively performed by Ghana’s quaint customisation. Needless to say, nothing of that sort happened. A little more genuine consultation with the Ghanaian tech community would have saved the country money and ensured that resources go towards more value-adding geolocation integration into service delivery instead of replicating pre-existing geotagging systems. As it is now, all the digital platforms serving Ghana simply use Google or other international digital geolocation tools, and not the national system.

National ID

The principle that national identification can be a critical foundation for public service delivery is not new. The World Bank’s ID4D initiative launched in 2014 builds on policy awareness dating back decades, with various European governments introducing national IDs in 1938 and thereafter before civil rights concerns led to a slowdown in their momentum. The Ivorien national ID Card scheme, for instance, has been running continuously since 2001.

It is undeniable that the Veep’s sponsorship of the Ghana Card project has led to the fastest and deepest enrolment of Ghanaians since efforts to roll out a National ID began in 2003. More Ghanaians than ever before now have a secure form of ID that is compatible with other digital services.

But a great deal of the good that could have been done by this system has been forgone due to the extreme profiteering approach adopted. The system as it currently exists is primarily a cash-cow for its enterprising private sector “partners”, who are not merely contractors but effective controllers and owners of the underpinning technology infrastructure.

Matters came to a head when the country was effectively subject to blackmail during the latest mass voters’ registration. The private contractors demanded millions of dollars before the country could commit to provide enough cards to first-time voters. In the end, plans to rely solely on the Ghana Card had to be abandoned. At the end of the exercise, it was noted that over 60% of young voters registering for the first time did not have a Ghana Card. High expense has prevented sufficient coverage despite the program costing over 40 times the cost per capita of India’s much praised model.

In a similar vein, promises to tightly integrate government services have failed to be realized because every such integration requires participating state agencies to pay millions of dollars to the private contractors for basic database linking.

Rather than focus on providing a low-cost KYC mechanism over the internet to boost the digital economy, the private vendors driving the Ghana Card are focused on selling hardware terminals for card validation to financial institutions, scuttling the government’s open banking promises. The dramatic resistance of the Ministry of Communications to a similar attempt to foist these terminals on telecom agents led to a bizarre situation where the Ghana Card was the sole document for SIM card registration yet telecom operators could not validate the cards in real-time. The country was bewildered to read letters from the National Identification Authority discrediting the approach of the Ministry and insisting on selling these devices and services.

Perhaps, the height of confusion was reached when a misguided effort to bypass the Ghanaian passport and embed the country’s core e-passport mechanism into the Ghana Card resulted in comical clashes with the world body at the helm of affairs, ICAO. In the end, promises to get all of ECOWAS to submit to Ghana’s model for e-Passport functionality failed as, obviously, most countries prefer to conform to ICAO’s pace and strategy. This is what happens when an initiative held up as a public good is in fact motivated primarily by private profit.

And a raft of others

In his digital champion heydays, not a day went by without the Veep launching one “transformative” digital project or the other. A careful assay of the outcomes of most of these projects lead to very sobering conclusions.

Since MASLOC, one of the government’s small business lending programs, was digitalized in 2020 to great fanfare as part of the Veep-led digitalization agenda, ostensibly to eliminate inefficiencies and graft, Ghana’s Auditor General has published scathing reports showing a degeneration in performance, including rising default rates, across activities such as its PINCO, poultry, and tricycle-acquisition projects.

In 2019, the Veep launched a national e-procurement system to fix bid-rigging and other procurement abuse only for the country to be thrust into procurement scandal after scandal, from the cathedral affair to the current Bank of Ghana mess. At one point, even the head of the procurement control agency was entangled in a bizarre “tenders for sale” scandal leading to his indictment. It goes without saying that the e-procurement system launched to great fanfare by the Veep has had no impact whatsoever across most procurement entities even in the central government.

Conclusion

In short, the hard pivot from economic transformation to digitalisation-for-transformation by the Veep has not shielded him and the ruling party from the looming confrontation with the government’s policy record in the 2024 elections.

And yet, to reiterate my earlier analysis, neither policy performance nor the failed coronation is definitive in assessing the chances of the Veep should he win tomorrow’s internal contest as predicted. His mould-breaking ascent has introduced certain uncertainties into the settled electoral calculus of Ghana that should give pause to those in the Opposition’s electoral strategy team celebrating the imminent collapse of the government at the 2024 polls. Their celebration may well be premature.

As of this moment, the 2024 chessboard is only getting set, and one-half of it is cast in the shadow of a man readying his fugu for a date with destiny.