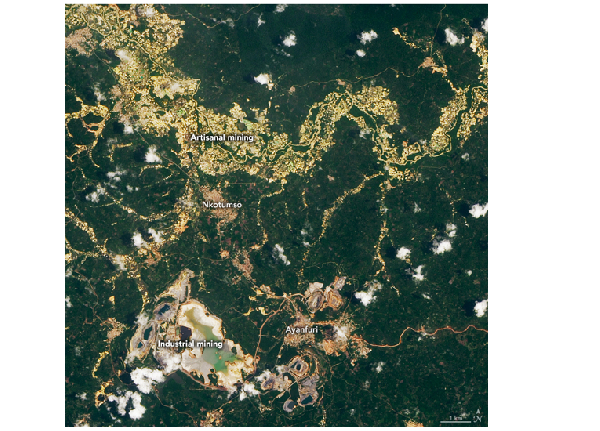

Image of a river destroyed due to galamsey activities

Image of a river destroyed due to galamsey activities

In Ghana, gold mining is not just an industry but a vital part of many rural communities. However, the rise of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) brings significant challenges that go beyond economic benefits.

This unregulated sector, which has surged over the last two decades, contributes to environmental degradation, deforestation, and ecosystem disruption.

A 2020 satellite image from NASA’s Landsat 8, reveals the extensive impact of these activities, highlighting the urgent need for government intervention and sustainable mining solutions.

Ghana’s southwestern region, often referred to as the “gold belt”, has become the epicentre of ASGM activities, with vast areas cleared for mining.

Unlike the large, organized zones of industrial mining, artisanal sites are scattered, leaving behind small irregular holes that visibly disrupt the landscape.

These sites stand in stark contrast to the organized, regulated industrial zones.

While ASGM contributes just one-third of Ghana’s gold production, its environmental toll is disproportionately severe, resulting in approximately seven times more deforestation than industrial mining operations.

Between 2005 and 2019, Ghana lost about 160,000 hectares of vegetation in this region, with 28% due to mining, 29% to urban development, and 17% to water conversion.

Agriculture and other factors contributed to the remaining 25%. A staggering 85% of mining-related deforestation during this period was due to ASGM, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas like riverine forests, which are critical for biodiversity, soil stability, and water regulation.

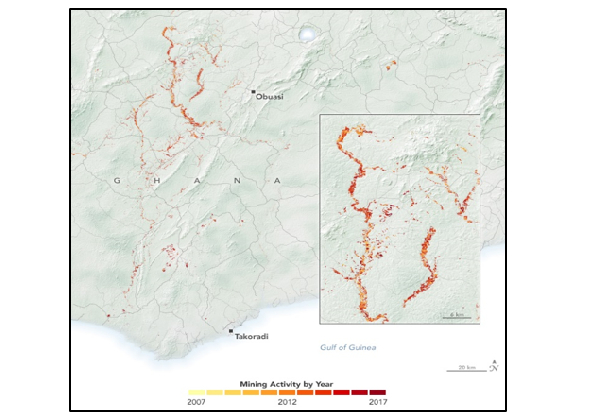

From 2007 to 2017, artisanal mining activities, especially near Kumasi, surged. Over 700 hectares of forests in protected zones were lost to artisanal mining activities from the same period.

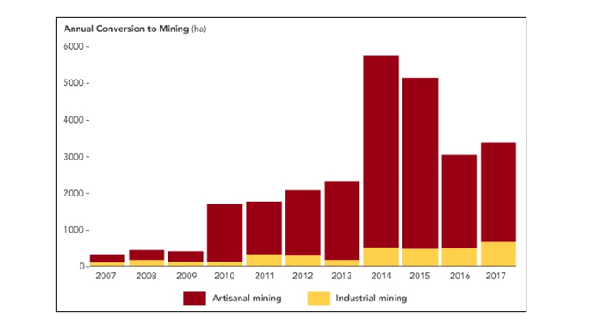

Even areas meant for conservation aren’t spared. Rising global gold prices—jumping from $700 per ounce in 2010 to $1,200 and peaking at $1,900 in 2014—drove a boom in mining activity.

The destruction was evident, with over 5,000 hectares converted for mining in a single year. The absence of environmental safeguards in ASGM has led to widespread deforestation and soil degradation, creating an unsustainable pattern of land use.

For many rural Ghanaians, where economic opportunities are scarce, ASGM is an attractive option. Armed with basic tools, thousands of small-scale miners, known locally as "galamsey" operators, flocked to gold-rich areas.

But the socio-economic drivers of ASGM are complex. High rural unemployment and the decline of traditional farming have pushed many into mining.

This shift has serious consequences: fertile agricultural land is often rendered unusable due to soil contamination and deforestation, undermining food security and local livelihoods.

The resulting biodiversity loss is not just an environmental issue but also an economic one, as many communities depend on these ecosystems for agriculture.

In contrast, industrial mining operations, while larger, have a relatively contained environmental footprint. Industrial companies must follow stricter environmental guidelines, such as land rehabilitation and waste management.

From 2005 to 2019, industrial mining accounted for just 14.3% of mining-related vegetation loss, largely due to regulatory oversight.

Despite legal frameworks governing mining, enforcement remains weak, especially for ASGM. The rise of illegal mining, or galamsey, has worsened the situation.

Government crackdowns, including military deployments, have had limited success due to corruption, lack of political will, and the sheer scale of the problem.

Addressing the environmental and social impacts of ASGM requires a multifaceted approach. First, stricter enforcement of mining regulations is essential.

The government should invest in better monitoring systems, possibly using satellite technology to detect illegal mining in real time. Stricter penalties for violations and greater transparency in issuing mining permits would also help curb illegal operations.

Second, promoting sustainable mining practices is crucial. Providing technical and financial support to artisanal miners to adopt mercury-free gold extraction methods, along with land rehabilitation programs, would help reverse environmental damage and create alternative livelihoods for affected communities.

Lastly, addressing the root socio-economic causes of ASGM is key. Rural development initiatives, particularly in agriculture and eco-tourism, could reduce dependency on mining for income. Education and awareness campaigns highlighting the long-term environmental and health risks of illegal mining would further support this effort.

The image was captured on March 2020, by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. The Highly textured landscapes tend to indicate artisanal mining due to the small holes compared to wider, smoother industrial areas.

map shows new mining activity over a subset of the study period from 2007 to 2017 near Kumasi, Ghana (The Darker orange and red represent more recent activity).

The bar chart visually depicts the amount of land converted by artisanal and industrial mining activities over the decade.