A graphical representation of the breakdown on PFJ expenditure

A graphical representation of the breakdown on PFJ expenditure

Government has spent an estimated GH¢2.9 billion so far on its flagship agricultural programme, Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ), since its introduction in 2017, according to minority lawmakers.

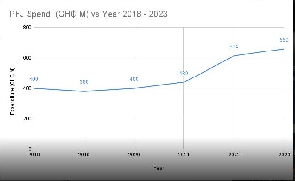

A breakdown of expenditure on the programme shows that government spent GH¢400million in 2018, GH¢380million in 2019 and some GH¢400 million in 2020. Additionally, GH¢439million was spent on the programme in 2021, GH¢614million in 2022 and GH¢660million in 2023.

Despite the huge sums spent, they said, the sector’s growth rate has painfully remained low at around 0.7 percent – with the country battling rising food inflation not seen in decades.

“Having inherited an agricultural sector with a growth rate of 2.7 percent in 2016, and after expending millions of cedis on PFJ for six years, agriculture growth currently stands at a disastrous 0.7 percent,” the deputy Ranking Member, Committee on Food, Agriculture and Cocoa Affairs, Dr. Godfred Seidu Jasaw, said in a press statement.

PFJ, launched in 2017, was intended to modernise agriculture, improve production and achieve food security and profitability for farmers. The first phase of the PFJ (crops) aimed to promote food security and immediate availability of selected food crops on the market, and also provide jobs.

Furthermore, he mentioned that headline inflation skyrocketed to 54.1 percent in December 2022 and currently stands at 43.1 percent.

It was against this background that he said the programme has been a monumental failure with very little to show.

The minority also raised concerns over an allocation of GH¢660million to the PFJ in 2023, despite government announcing that PFJ’s first phase ended in December 2022.

The statement further demanded clarity over the 2023 allocation, insisting that government should clarify what the money is meant for.

Meanwhile, President Nana Akufo-Addo last month launched the PFJ’s second phase – which represents a shift in policy direction from input subsidy under the first phase to an input credit guarantee system.

“Why has government failed to support food-crop farmers in Ghana since January 2023? Private agro-dealers and aggregators have been implementing various forms of input credit support schemes to farmers for many years now; what exactly will this new PFJ input credit do differently?

“We still cannot account for the so-called increased production figures that were being churned out by the Minister for Agriculture. Where is the maize? Where is the rice? Where are the soybeans? One would have reasonably expected to have a food glut in Ghana by now, which would have driven down prices,” he stated.

The statement said there are identified limitations in the programme’s first phase – including high budgetary strain on government; adoption of the value chain approach; limited access to agricultural credit; low prioritisation of national strategic stock; and limited focus on the needs of commercial small-, medium- and large-scale farmers.

According to the minority member, government renamed PFJ from an original initiative of the erstwhile President Mahama/NDC administration dubbed ‘Modernisation of Agricultural Productivity to the Local Economy’ (MAPLE). This programme was to be funded by the Canadian government with C$125million, equivalent to US$120million.

Dr. Seidu Jasaw maintained that after a study of the PFJ Phase 2 programme document, it has been identified there is nothing substantially new in it, and that it will not deliver any significant march to the country’s food security.

“We contend that the objective of this new scheme is to erase the mess from the programme’s failed first phase, and create a face-saving platform to continue the dissipation of our scarce resources through establishments by ‘this family and friends’ government,” the statement captured.

Government was also asked how it is going to protect the smallholder farmer from profit motives and market risks under which the input dealers operate; and how it will achieve import substitution for critical commodities like rice, maize and poultry since there are no measures in place to reduce input/production costs, among others.

Dr. Seidu Jasaw noted that with the IMF programme, the economy cannot support an input subsidy programme.