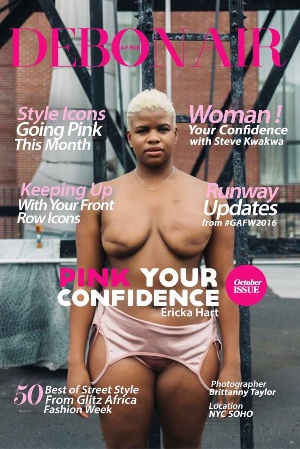

October issue of Debonair Afrik

October issue of Debonair Afrik

Being diagnosed with breast cancer is a life-changing experience. It can be tremendously difficult to accept the accept for the first time and even harder to know how to proceed, no matter your prognosis.

While everyone’s journey is unique, knowing that others before you have been through something similar can give you the guidelines , strength and inspiration you need to keep everything in perspective.

Meet Ericka Hart , A young and Confident lady who was Diagnosed with BREAST CANCER four months before her wedding . As she narrates ...

In May 2014, standing in Wall Street preparing to walk into a Sephora on my lunch break, then looked down and saw that my doctor was calling me. I had been waiting for his call after a week of tests on my breasts after finding a lump in the shower.

I do not remember if he asked how I was or if he just said it, but all I remember from that phone call was being diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer; asking “am I going to die?”; and his reassuring response of “no” (an exchange which I now find so funny and unavoidably mortal).

I hung up the phone and sat in the middle of Wall Street, crying until I mustered the nerve to call my wife at the time, she arrived in Wall Street in record timing. I called my Dad and he expressed remorse and attempted to cheer me up with, “Well, now you will have new breasts.” He was right.

Two months later, I was in a hospital gown being rolled under the stereotypical fluorescent lighting after a night of cutting my locs and dying my hair pink and failed attempts to cast the breasts that I had for 28 years in a clay mold.

I woke up after six hours of surgery to bright lights. kicking my blanket off. the nurse stood over me, I was insanely hot. I tried to move the blankets off of me, but realized my arms did not have the same mobility. I had lymph nodes removed from both of my underarms in an effort to avoid spreading.

I was in pain. I knew my family and friends had been waiting for me and I just wanted to get to them. In addition to having lymph nodes removed, I had my breast tissue removed and tissue expanders put in its place to expand the skin such that reconstructive surgery can take place at a later time.

Diagnosed four months before my wedding, I focused on my wedding as a form of self-care therapy; vanity being the only part of my life I felt I could still control.

After a double mastectomy there are surgical drains that collect excess fluids. They need to be dumped and measured each day. The tissue expanders feel like Tupperware bowls full of a lighter version of cement.

Putting on shirts is a privilege now—lifting my arms during recovery was virtually impossible. Due to the pain of the tissue expanders, I could barely sleep on my side, so I slept on my back for a year after which i had reconstructive surgery. My plastic surgeon is the most body positive, affirming person I have ever met.

She gave me the options of silicon/saline implants and a flap procedure (involves removing stomach tissue and placing it in the breasts. I had to wait a year, as I was on chemotherapy).

I noticed that my plastic surgeon had to search and search for an example of a black woman’s double mastectomy. I thought this might just be indicative of her client base, but then I started doing my own research.

If you run a Google search right now, on “double mastectomy” what you would mostly find are white people’s double mastectomy surgeries.

According to research, black women have seen increased rates of breast cancer over the past ten years leading to increased death rates. Where are the examples of black and brown folks who had these surgeries? Where were the images of their double mastectomies (mastectomies, lumpectomies, etc.)?

The lack of black and brown visibility in a simple Google search for breast cancer reconstructive surgery is just a microcosm of the ways that black women are left out of the conversation around breast cancer and indicative of black women’s bodies being highly sexualized and at the same time disposable. A Google search was not the first time I have not seen myself, us, represented in a subculture. As a queer black woman, it can be an uphill battle finding community in even what is claimed to be the most diverse city in America, New York City.

Ericka Hart’s decision to attend Afropunk this year topless was to provide the visibility that I wanted to see and that we need. Afropunk has been a festival I have attended for the past six years (even on chemo one of those years). Punk to me means standing in your truth and resisting white supremacist, patriarchal notions of existence. I wanted people to see me such that they saw themselves, their mothers, lovers and friends.I was diagnosed at 28 and although major cancer non-profits exist to provide visibility for cancer at young ages, I still had doctors surprised by my diagnosis, given my age.

As she went topless at Afropunk to challenge the notion that “female-bodied” people can’t take their shirt off due to some androcentric, understated rule that it should not happen in public.Ericka Hart took her shirt off at Afropunk to not only to be seen as a cancer warrior, but to reclaim her sexuality. Breast cancer patients are so often painted as walking inspirational beings, thus effacing any opportunity to be seen as sexy or erotic.

Although I live 15 minutes away from Barry Commodore Park, I commuted to the festival wearing a top and vacillated between taking my top off and abandoning the idea altogether. Maybe I would be too scared at what people would say, perhaps I wouldn’t be able to bare the attention. As I walked around the park topless, I remember feeling this sense of familiarity. I did not look like everyone else, but that was familiar. People looked at me strange, but that was also familiar. Being topless at a festival after a double mastectomy was just a metaphor for my experiences as a black queer woman. In essence, standing topless was not difficult, just familiar. Queer, cancer and black: a lot of intersections of alone.

Each day of the festival, I remembered that me taking my top off had very little to do with me. That I was giving myself away to awareness, to my community and in honor of my Mom who died of breast cancer when I was 13 and was the epitome of generosity and consistent resistance to conventional notions of cancer, of any conventions.