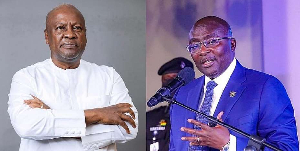

Dr Bawumia and John Dramani Mahama

Dr Bawumia and John Dramani Mahama

The Ghanaian political landscape has over the past two years been dominated by two political heavyweights all vying for the enviable position of President of the Republic of Ghana. It is important to note that one has occupied the seat in the past and the other is looking forward to doing the same.

The interest in these two candidates stems from a near-perfect two-party political system since the beginning of the 4th Republic in 1992. Over the years, it is important to note, that these parties have each ruled Ghana for nearly sixteen years each. What makes this current dispensation interesting for many of us is the flagship policies outlined by the flag bearers of these two parties.

The New Patriotic Party under the leadership of Vice President Alhaji Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia opines that the way forward for Ghana is a Digital Economy linked to every household, every government office, every school and every business.

The seamless linkage between these, according to him will create a more robust economy based on international best practices and an anchoring into the 4th industrial revolution. On the part of former President John Dramani Mahama, Ghana's economy needs a reset, a ‘big push’ joined to the umbilical cords of a 24-hour economy where jobs are readily available to millions of Ghanaians based on a shift system.

The difficulty I have and I dare say others have is the lack of cohesion in explaining what both policies mean for the Ghanaian economy. So what are these policies and what are the challenges we are likely to face with the implementation of either one of them?

Fourth industrial revolution and Bawumia's digital economy policy

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) represents a transformative period characterized by the fusion of physical, digital, and biological systems, significantly altering industries and society. This revolution builds on the technological advancements of the Third Industrial Revolution, such as automation and information technology. It extends then with innovations like artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and advanced robotics. One of the most profound impacts of 4IR is its potential to reshape economies and labour markets. Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, posits that 4IR will lead to unprecedented changes in how we live and work, emphasizing that this revolution is distinct in its velocity, scope, and systems impact (Schwab, 2017). He argues that the fusion of technologies blurs the lines between physical, digital, and biological spheres, creating new opportunities and challenges for humanity.

Jeremy Rifkin, an economic and social theorist, also highlights the implications of 4IR, particularly its role in the transition towards a more sustainable economy. Rifkin (2019) asserts that the convergence of digital technologies with renewable energy sources and smart infrastructure could pave the way for a "third industrial revolution," potentially leading to a more inclusive and circular economy. This perspective aligns with the broader discourse on sustainable development, emphasizing the need for innovative solutions to address environmental and social challenges.

Erik Brynjolfsson, a prominent scholar in digital economics, focuses on the labour market disruptions caused by 4IR. Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) argue that technological advancements, particularly in AI and machine learning, lead to increased automation, which could displace traditional jobs. However, they also suggest that these technologies could create new opportunities for workers, provided that adequate policies and education systems are in place to equip the workforce with the necessary skills.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution presents a dual-edged sword: it promises economic growth, sustainability, and enhanced quality of life; on the other hand, it poses significant challenges, including job displacement and social inequality. As Schwab (2017) emphasizes, the key to navigating this revolution lies in collaborative efforts among governments, businesses, and civil society to harness the benefits of technology while mitigating its risks.

Dr Bawumia clearly understands that for Ghana to be part of a global digital ecosystem, the country needs to create digital channels to enhance productivity for all Ghanaians. The Digital economy can transform everyday living and the lives of millions. Taking a cursory look at what has been done so far; there is no doubt that interoperability, digital address systems, and the various e-platforms created to foster cooperation and accessibility in governance are foundation stones for a much broader cognitive response to a global digital ecosystem.

The digital economy, driven by advancements in information technology, connectivity, and data analytics, has become a critical force shaping the global economic landscape. It encompasses a range of activities that leverage digital technologies, including e-commerce, digital payments, cloud computing, and data-driven decision-making. The benefits of a digital economy are vast, influencing productivity, innovation, and economic inclusion.

One of the most significant advantages of the digital economy is its potential to enhance productivity and efficiency across various sectors. Erik Brynjolfsson, argues that digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data analytics can drastically improve decision-making processes and operational efficiencies in businesses (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014). By automating routine tasks and providing data-driven insights, organizations can reduce costs, improve service delivery, and increase overall productivity.

Another key benefit of the digital economy is its capacity to foster innovation. Digital platforms and ecosystems enable new business models, products, and services that were previously unimaginable. Shoshana Zuboff, a renowned scholar, emphasizes the role of digital platforms in creating new markets and disrupting traditional industries. Zuboff (2019) highlights how companies like Google, Amazon, and Uber have leveraged digital technologies to revolutionize their respective sectors, driving competition and innovation that benefits consumers.

Additionally, the digital economy plays a vital role in promoting economic inclusion and access to global markets. Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel laureate known for his work on microfinance, underscores how digital technologies can empower marginalized communities by providing access to financial services and online markets.

Yunus (2017) notes that digital platforms can democratize opportunities, enabling small businesses and entrepreneurs in developing countries to participate in the global economy, thus reducing poverty and promoting inclusive growth. No country in modern times can neglect the digital economy if it is to feature prominently. According to the World Bank, the digital economy is rapidly expanding, and the workforce in digital spaces is growing significantly worldwide.

Approximately 2.6 billion people were offline as of 2023, reflecting a substantial digital divide, particularly in low-income countries where internet usage remains low compared to high-income nations. However, the rise of digital jobs, especially platform-based work, provides new income opportunities. It poses challenges for job security and regulation, particularly in developing countries where labour market conditions differ significantly from those in developed nations. Ghana can correct this challenge by providing access to the internet for all Ghanaians irrespective of where they live. According to Geopoll, as of 2024, Ghana has around 38.95 million mobile connections, about 113% of the country's population. This high percentage indicates that many Ghanaians use multiple SIM cards, a common practice in many African countries.

The penetration of mobile internet is significant, with approximately 70% of mobile connections in Ghana being broadband, ranging from 3G to 5G networks. This growth reflects an increasing adoption of mobile internet services across the country. However, the World Bank emphasizes the need for inclusive policies to foster digital skills and facilitate participation in the global digital economy, aiming to bridge the gap in digital access and create more equitable opportunities for digital employment worldwide. Digital transformation drives economic growth while balancing opportunities with necessary regulations. This remains crucial for sustainable development.

Furthermore, digital connectivity refers to the ability of individuals, businesses, and governments to access and utilize digital technologies, including the Internet, mobile networks, and digital services, to connect the broader world. It encompasses the infrastructure, platforms, and tools that enable digital interactions, such as broadband networks, data centres, and digital devices. Digital connectivity is a critical component of the modern economy, fostering communication, innovation, and economic growth. African countries like Ghana can expand their digital frontiers to meet global expectations by focusing on key areas such as infrastructure development, digital literacy, and regulatory frameworks.

Digital infrastructure, including high-speed internet, reliable power supply, and modern telecommunications networks, forms the backbone of digital connectivity. As highlighted by Minges (2016), improving broadband infrastructure is essential for countries to participate effectively in the digital economy. In Ghana, expanding fibre optic networks, increasing the number of data centres, and enhancing mobile broadband coverage are crucial steps. These efforts can be supported by public-private partnerships, which can mobilize the necessary investments and expertise.

Digital literacy is critical for maximizing the benefits of digital connectivity. According to Castells (2010), digital literacy goes beyond basic computer skills; it involves the ability to critically navigate and utilize digital platforms for economic, educational, and social purposes. Ghana should invest in programmes that equip citizens with the skills to thrive in the digital age. Initiatives such as coding boot camps, digital skills training for entrepreneurs, and tech hubs can play a vital role in building a digitally savvy workforce.

A supportive regulatory framework is also essential to fostering innovation and expanding digital frontiers. Stiglitz (2019) emphasizes that governments should balance regulation and innovation, ensuring that digital markets are fair, transparent, and inclusive. In Ghana, regulatory reforms that simplify business processes protect data privacy, and support the growth of digital start-ups can encourage local and international investments in the digital economy.

Collaboration with regional and international partners may accelerate digital transformation. Initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) may enhance digital trade and connectivity across borders, enabling countries like Ghana to access larger markets. Partnerships with global tech companies can also provide access to advanced technologies, training, and funding. Expanding digital frontiers in African countries like Ghana requires a multifaceted approach that includes infrastructure investment, skills development, regulatory reform, and international collaboration. By addressing these areas, Ghana can position itself as a competitive player in the global digital economy, enhancing economic opportunities and improving the quality of life for its citizens.

Mahama's big push and 24 Hour Economy

The 'Big Push' is a concept in economic development theory that suggests a coordinated, large-scale investment effort is necessary to overcome structural barriers to economic growth in underdeveloped countries. This theory argues that isolated, small-scale investments are insufficient to stimulate significant economic growth; instead, substantial and synchronized investment across various sectors of the economy is required to achieve a transformative impact.

The Big Push theory, first formalized by economist Paul Rosenstein-Rodan in 1943, emphasizes the presence of indivisibilities and complementarities in the economy. Rosenstein-Rodan argued that because industries and sectors are interdependent, small, uncoordinated investments will not suffice; instead, a simultaneous push across multiple sectors is needed to create a balanced and sustainable growth path (Rosenstein-Rodan, 1943). The theory also stresses the importance of positive externalities and scale economies. Murphy, et al (1989) elaborate that large-scale investments generate externalities that benefit other sectors, leading to a virtuous cycle. For instance, investing in infrastructure not only boosts the construction sector but also enhances productivity in manufacturing and services by reducing costs and improving connectivity. The 'Big Push' model addresses coordination failures that often lead to poverty traps, where economies remain stagnant because individual investors do not account for the complementary nature of their investments. Kremer (1993) and others argue that without coordinated investment, economic agents fail to generate sufficient demand for each other's products, thus preventing growth. The 'Big Push' aims to overcome this by coordinating investments that elevate the entire economy. Governments play a crucial role in implementing the Big Push by coordinating investments, mobilizing resources, and creating an enabling environment. Jeffrey Sachs (2005) suggests that without significant public intervention, private sector investments may fall short of achieving the scale necessary for the Big Push to be effective.

John Mahama's Big Push is nothing short of a short-term measure to deal with challenges. His offer of a ten billion dollar investment in infrastructure is ambitious as it may leave other sectors in dire need of cash for development. The reason for this theory according to Rosenstein-Rodan was to bridge the gap between wealthy countries and poor nations. Unfortunately, it seems that the world has moved on from the 'big push' theory many years ago. As of 2024, Ghana's GDP growth rate is projected to be 3.4%, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB).

This forecast reflects a gradual recovery from the previous year's growth of 2.9%, influenced by global challenges such as geopolitical tensions and economic constraints. Looking ahead, the AfDB anticipates that Ghana's GDP could grow further to 4.3% in 2025, driven primarily by the services and industrial sectors alongside increased private consumption and investment. For a ten billion dollar infrastructure investment to come to light, it means the Ghanaian economy must grow 8-10% according to many economists.

The current dispensation, with rising debt, rising cost of living, and rising inflation, cannot sustain a ten billion dollar investment in infrastructure. A more feasible approach is what is known as sector packaging where several sectors are tied together to offer the best investment outcomes. For instance, brick and mortar do not make an economy resilient. Investment in several private sector initiatives together with social interventions and mindset tuning create a better platform for far-reaching investments in the country. Implementing this approach presents several significant challenges for any Mahama-led government considering Ghana's economic standing today.

One of the primary challenges is the difficulty in coordinating investments across different sectors. According to Rosenstein-Rodan (1943), the success of the Big Push depends on simultaneous investments in complementary industries. However, coordinating these investments among private investors, governments, and international donors can be complex and often leads to inefficiencies and missed opportunities due to misaligned incentives. The Big Push requires substantial financial resources that many developing countries lack. Sachs (2005) points out that the scale of investment needed is often beyond the capabilities of most developing economies, which struggle with limited access to capital markets, low savings rates, and high levels of public debt. These financial constraints make it challenging to generate the required investment volume for a successful Big Push. Effective implementation of the Big Push requires strong institutions to manage and coordinate investments, enforce contracts, and maintain economic stability.

However, many countries that attempt this strategy face institutional weaknesses such as corruption, weak governance, and inadequate legal frameworks, which can undermine the effectiveness of large-scale investment projects (Murphy, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1989). There is a risk that resources may be misallocated due to poor planning, political interference, or a lack of clear economic priorities. Hausmann and Rodrik (2003) argue that governments, especially in developing countries, may not always have the necessary information or capability to direct investments effectively, leading to suboptimal outcomes. Countries that have tried the 'Big Push' are often vulnerable to external shocks, such as global financial crises, commodity price fluctuations, or geopolitical events. These shocks can disrupt investment flows and hinder the progress of development projects, as seen in several countries that have tried to implement large-scale economic transformation (Krugman, 1994).

Several countries have attempted to implement ‘Big Push’-style economic policies, often with mixed results. In the 1960s and 1970s, South Korea successfully implemented a coordinated investment strategy, focusing on industrialization and infrastructure development. The government's role in directing investments and coordinating between the public and private sectors was crucial to the country's rapid economic transformation (Amsden, 1989). During the 1950s and 1960s, Brazil pursued a ‘Big Push’ strategy with large-scale investments in infrastructure and industry under the Kubitschek government's "Plano de Metas" (Plan of Goals). While this led to industrial growth, the policy also created significant economic imbalances and high inflation rates (Bresser-Pereira, 2009). India's Five-Year Plans in the post-independence period represented a Big Push approach, focusing on heavy industry, infrastructure, and state-led development. Despite some successes, the plans often struggled due to bureaucratic inefficiencies and coordination challenges (Mahalanobis, 1955). Several African countries, including Nigeria and Ghana, have attempted Big Push policies, particularly in infrastructure development and industrialization. However, these efforts have often been hindered by financial constraints, governance challenges, and external economic shocks (Ndulu et al., 2007). There is enough evidence to show that the 'Big Push' is a recipe for disaster and will add to Ghana's economic woes. Will John Mahama's 24-hour economy fare any better?

WHAT IS A 24 HOUR ECONOMY?

A 24-hour economy, also known as a "round-the-clock economy," refers to an economic system that operates continuously throughout the day and night, without any formal closing hours. This concept is primarily associated with urban areas where businesses, services, and activities are designed to cater to the needs of individuals at any time, enhancing economic efficiency and flexibility. The 24-hour economy is characterized by the uninterrupted operation of essential services like transportation, healthcare, retail, entertainment, and financial services, contributing to increased economic activity and urban dynamism. B C A 24-hour economy allows businesses, such as supermarkets, restaurants, and entertainment venues, to remain open at all hours, providing greater convenience for consumers and opportunities for businesses to generate revenue outside traditional working hours (Shaw, 2018). The 24-hour economy creates jobs that accommodate non-traditional working hours, such as night shifts and flexible schedules, which can be particularly beneficial for students, part-time workers, and those seeking additional income (Roberts & Eldridge, 2009). Expanding economic activities beyond traditional hours can revitalize urban spaces, reduce congestion by spreading demand across more hours, and make cities more attractive for tourism and investment (Gwiazdzinski, 2014). With the rise of e-commerce, online banking, and 24-hour customer service hotlines, a 24-hour economy caters to the increasing demand for instant access and service provision, further blurring the line between day and night operations (Karowski, 2020).

Despite the obvious reasons for a 24-hour economy, the continuous operation of a city can lead to noise pollution, increased energy consumption, and the need for enhanced security measures, which can affect the quality of life for residents, particularly in urban areas (Roberts, 2006). Non-standard working hours, such as night shifts, can impact the health and well-being of workers due to disrupted sleep patterns, increased stress, and a higher risk of accidents (Spurgeon, Harrington, & Cooper, 1997). The transition to a 24-hour economy requires cities to invest in public infrastructure, transport, lighting, and security services to support night-time activities safely and efficiently (Hadfield, 2015). There is no doubt that many countries operate a 24-hour economy already and in Ghana, the same can be said of several sectors that operate 24 hours.

The challenge former President John Mahama will have is the lack of supporting infrastructure to build a cohesive non-stop economy. Ghana's infrastructure is weak and needs an overhaul. The country is certainly not ready for a full-blown 24-hour economy. Ghana's golden triangle cities of Accra, Kumasi and Sekondi-Takoradi may serve as pilot cities.

While both models have their benefits, scholars argue that the digital economy may offer more extensive benefits in terms of global reach and efficiency, especially in a world increasingly reliant on technology. However, a 24-hour economy might offer immediate benefits related to increased economic activity and consumer convenience. The choice between the two depends on specific objectives and societal needs. The choice for Ghanaians will be to decide who has the best policies.

A digital economy with an insatiable appetite for growth, global reach and non-stop technological advancement which in itself offers opportunities for over one million Ghanaian entrepreneurs currently using the internet for business with the potential for exponential growth or a localised 24-hour economy which requires huge investments from business owners to expand their businesses, provide additional healthcare, conditions of service for workers. As much as we already have a 24-hour economy provided by the digital space, it may be incorrect to suggest that what former president John Mahama proposes will be a game changer within his four-year term.

A 24-hour economy, which aims to keep businesses and services running around the clock, can have several potential drawbacks. Let me reiterate a few of them: Maintaining operations 24/7 can lead to higher costs in terms of utilities, wages (including overtime or higher pay rates for night shifts), and security. Also ensuring infrastructure is always operational and maintained can be expensive. Night shifts and irregular working hours can negatively impact employees' physical and mental health, leading to issues such as sleep disorders, increased stress, and reduced work-life balance.

Moreover, irregular hours can disrupt personal and family life, affecting relationships and overall quality of life. Operating at all hours can increase the risk of accidents and injuries, particularly during night shifts when fatigue levels are higher. To add to all these drawbacks, higher night-time activity can lead to increased crime rates or safety concerns, necessitating additional security measures. In some cases, a 24-hour operation might lead to overcapacity where demand does not justify the extended hours, leading to inefficiencies and wasted resources. The economic benefits of extended hours may diminish if the additional revenue generated does not offset the increased costs. A 24-hour economy can lead to increased energy use, contributing to higher carbon emissions and environmental strain whilst constant activity can disrupt local communities, leading to noise pollution and reduced quality of life for residents. Finally, extended business hours may blur the lines between work and personal life, affecting overall societal work-life balance.

It is my opinion that the choices are clear as we approach what is a look to the future where the sky is certainly not the limit. The decisions we make should be based on the future of our children and where we hope to be on the global stage shortly. The challenges are surmountable if we all put our hands on the plough and make efforts to till the land of our fathers. Posterity will judge us harshly if we fail.

JOT Agyeman

Johnagyeman@yahoo.com

The writer is a Media and Communications Consultant and a Lecturer in Cognitive Techniques and Creative Design.