One pathologist decides a cancer diagnosis is

One pathologist decides a cancer diagnosis is

Pathology errors can have serious effects on cancer diagnosis & treatment. It almost goes without saying that errors in the pathology laboratory can have serious consequences for cancer patients. But although everyone knows that pathologists, being human, make mistakes, few physicians discuss it, and almost no research has been done to assess the type and extent of errors and the consequent effect on cancer care. A team led by Stephen S. Raab, MD, Professor of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, catalogued and assessed such mistakes at four institutions. The results were published in the November 15 issue of Cancer.

Dr. Raab and his colleagues reviewed the clinical records of all gynecologic (Pap tests) and non-gynecologic errors. Then an independent clinical outcomes data collector reviewed the records. Finally, a pathologist assessed the clinical severity of the errors, rating them as follows:

i. No harm: Medical intervention acted regardless of an erroneous diagnosis.

ii. Near miss: Intervention before harm occurred or no intervention because of the erroneous diagnosis.

iii. Minimal harm: Further unnecessary noninvasive diagnostic testing, delay in diagnosis or therapy, or minor morbidity due to further diagnostic tests or treatment predicated on the error.

iv. Moderate harm: Further unnecessary invasive diagnostic tests, a delay of more than six months in diagnosis or therapy, or major morbidity lasting less than six months.

v. Severe harm. Loss of life or limb or morbidity lasting more than six months.

What the Result Showed

There were more errors for non-gynecologic specimens than for gynecologic ones. Error frequency in the study, regardless of the type of specimen, depended on the institution; he added, for some, the error rate was more than 10%. All institutions showed a relatively high number of errors in specimens from the urinary tract and lung. Most were attributed to cytology rather than surgical sampling or interpretation. “These are difficult areas from which to obtain samples,” Dr. Raab explained.

No Standardization

The study authors noted that currently, there is no standardization of laboratory practices. Pathologists' experience, subspecialty practices, training programs, methods of preparing specimens, and quality assurance systems vary from institution to institution.

“We believe that differences in test ordering contribute to clinical sampling errors. For example, clinicians who bypass noninvasive cytologic diagnostic techniques for more invasive surgical techniques may have a higher rate of more accurate cancer diagnoses, but with higher costs, morbidity, and mortality,” Dr. Raab said. In addition, the effect of diagnostic errors on patient outcomes is largely unknown, but thinks about the havoc wreaked by, for example, 150,000 Pap test mistakes each year (assuming 50 million annual tests).

“I think government regulations would have to be instituted, with penalties for noncompliance, or maybe financial incentives for quality care as are happening in other areas of medical practice. But whatever you do, pathology practice is still a matter of individual competence and responsibility.”

“The diagnosis is made by a human,” said lead author Dr. Joann Elmore, of the University Of Washington School Of Medicine in Seattle. “There is no molecular marker or machine that will tell us what the diagnosis is.” Elmore said pathologists are not to blame for inconsistent results, however. The cases tend to be difficult to interpret. “I had my own skin biopsy about a decade ago,” she said. “I ended up getting three different interpretations from three different people.” “I realized this was an area I wanted to study and quantify,” she said.

For the new study, the researchers used 240 skin samples broken into sets of 36 or 48. The sets were then sent to 187 pathologists in 10 states for diagnoses. The same pathologists were asked to review the same set of slides at least eight months later. For the earliest melanoma, known as stage 1, about 77 percent of pathologists issued the same diagnoses in both phases of the study. Similarly, about 83 percent of pathologists issued the same diagnoses twice for the most advanced melanoma cases.

Pathologists were less likely to confirm their diagnoses during the study’s second phase for melanomas in stage 2 through 4, according to the results of The BMJ. The researchers also assembled a panel of three experienced pathologists to review the cases. The proportion of diagnoses the panel agreed with varied from 25 percent for stage 2 to 92 percent for stage 1.

Overall, the researchers say, if real-world melanoma diagnoses were reviewed by such an expert panel, only about 83 percent would be confirmed. They estimate that 8 percent of real-life cases are likely assigned too high a stage. About 9 percent of cases are assigned too low a stage. “Thankfully most of the biopsies are not of invasive melanoma,” said Joann G Elmore, MD, MPH. Dr Ashfaq Marghoob, a dermatologist with Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, said the results show that pathologists have high certainty when diagnosing biopsies that fall on the extremes of the stages. “All the in-between cases, there is potential you may waver,” said Marghoob, who wasn’t involved with the new study. “For me, it’s a study to (remind doctors that) pathology is not an exact science,” said Marghoob.

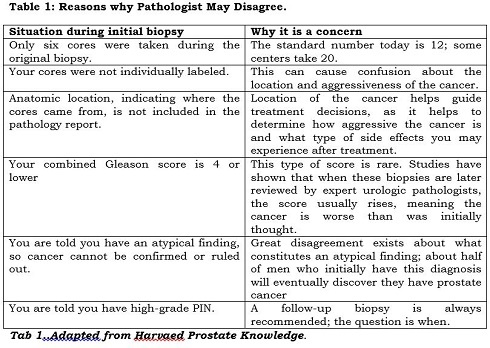

Consider this all-too-common scenario: One pathologist decides a cancer diagnosis is “definitive,” but another, looking at the same biopsy results, calls it “suspicious,” but not necessarily cancer. Who is right, and why do pathologists disagree? Some disagreements involve objective factors, such as how biopsies are done. Usually, though, pathologists disagree when it comes to interpretation and judgment — both subjective qualities.

It’s always a good idea to ask a second pathologist to review your pathology report and take a second look at your biopsy tissue (usually contained in slides that can be transported from one medical facility to another). This ensures that at least two pathologists agree on the diagnosis, which will give you and your doctor more confidence in developing a treatment plan. However, in certain circumstances, you may want to undergo a second biopsy

Another study examines factors that affect accuracy and reliability of prostate cancer grade. The authors compared Gleason scores documented in pathology reports and those assigned by urologic pathologists in a population-based study by Goodman et al 2013

A stratified random sample of 318 prostate cancer cases diagnosed was selected to ensure representation of whites and African-Americans and to include facilities of various types. The slides borrowed from reporting facilities were scanned and the resulting digital images were re-reviewed by two urologic pathologists. The agreements between reviewers and between the pathology reports and the “gold standard” were examined by calculating kappa statistics. The researchers concluded that the level of agreement between pathology reports and expert review depends on the type of diagnosing facility, but may also depend on the level of expertise and specialization of individual pathologists.

Inconsistency in sampling and labelling

There is little uniformity among medical facilities with regard to the number of cores removed during a biopsy and how they are labelled. Sometimes the cores are submitted to the pathology lab in two containers labelled simply “right” and “left,” referring to the side of the prostate they were taken from. Or worse, the cores are jumbled in a single container without any location specified. In this situation, you may end up with an overall Gleason score that averages all involved needle biopsy specimens as if they were one long positive core. This is far from ideal, and maybe one reason to consider having a biopsy repeated.

Knowing the anatomic location of any cancerous tissue is important for a number of reasons. This information helps to determine whether cancer is unilateral (confined to one side of the prostate) or bilateral (affecting both sides), and to estimate how likely it is that the cancer has spread or might do so in the future.

For instance, if cancer-containing cores are removed from the base of the prostate gland, the tumour is probably located near the seminal vesicle, which stores prostatic secretions and semen. (If cancer is in the seminal vesicle, it has migrated out of the prostate, signalling that more-widespread cancer may be present.) On the other hand, if the cancer is at the apex, it may impinge on the bladder neck or lower bladder, posing challenges for the surgeon, who wants to remove the entire cancer without affecting continence. Clearly, these represent very different scenarios when it comes to treatment and potential side effects such as erectile dysfunction or incontinence.

In addition, the anatomic location of specimens helps pathologists recognize and try to avoid certain diagnostic pitfalls: for instance, the tendency to confuse benign seminal vesicle tissue with high-grade PIN at the base of the prostate, or to mistake the Cowper’s gland, located adjacent to the urethra, for cancer at the apex. Details about location are also useful in making sure the same site is targeted in a repeat biopsy. In addition, mapping the distribution of cancer may help in planning the field of radiation therapy or influence decisions about nerve- or bladder-neck–sparing surgery during radical prostatectomy.

Another reason for knowing the location of the cancer is that this information can help determine whether extracapsular extension (ECE) — the spread of prostate cancer beyond the outer lining of the prostate — has occurred. Scientists have developed mathematical models known as nomograms that use systematic analysis of biopsy results from each lobe of the prostate, combined with PSA levels and digital rectal exam results, to predict the likelihood of ECE before planning treatment.

Differences in Gleason scoring

Different pathologists may also assign a different Gleason score to the same biopsy sample. Pathologists determine the grade of a lesion visually. Therefore, the score is only as good as the pathologist examining the tissue, as well as the quality of the tissue itself. One pathologist may grade a given biopsy a 3 + 4 (moderate risk) while another may interpret the same tissue as 4 + 3 (higher risk). In other situations, the discrepancy is even greater, to the point where one pathologist calls the cells cancer and another does not.

Different opinions about perineural invasion

Your pathology report may contain a finding of perineural invasion (PNI). Not to be confused with PIN, PNI describes cancer that tracks along or around a nerve. There is no consensus as to the clinical significance of such a finding.

One small study, involving 42 highly experienced urologists, found that most did not consider a finding of PNI important and fewer than half thought it should even be included in a pathology report. But 10 of the urologists — almost a quarter of the group — thought that PNI was clinically important, and said it would guide their treatment recommendations. For example, they said they would not perform nerve-sparing surgery on the side of the prostate where PNI was found on needle biopsy. Interestingly, the more radical prostatectomies the surgeons had performed, the more likely they were to consider PNI clinically important.

Problems distinguishing benign mimics

Numerous benign mimics of prostate cancer exist, but these can be difficult to distinguish from cancer. The most common mimics are partial atrophy of tissue and crowded benign glands. Others include complete atrophy of tissue, adenosis, seminal vesicle tissue, and granulomatous prostatitis. If you see any of these terms on your report, be assured they are no cause for apprehension. But they can be tricky for pathologists to identify.

Because of the challenges posed by benign mimics, a diagnosis of cancer will often be verified by immunohistochemistry (IHC), which uses certain antibodies to stain for cancer or its mimics. Just be aware that occasionally this process can produce both false-positive results (indicating cancer is present when it is not) and false-negative results (ruling cancer out when it is present). In conclusion, it’s always wise to seek a second opinion about your original biopsy, by having another pathologist review your pathology report and your biopsy slides. In the following circumstances, you may want to consider undergoing a second biopsy, possibly at a medical facility that performs saturation biopsies. See you next week