Sea mining, or deep-sea mining, has emerged as a hot topic in the global conversation around resource extraction. With the increasing demand for rare minerals such as cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese, which are critical for industries like renewable energy, electric vehicles, and electronics, companies and governments are looking to the ocean floor as a potential treasure trove. However, as the push for sea mining intensifies, so too do the concerns about its environmental impacts. This article explores the opportunities and risks associated with sea mining and discusses the steps being taken to address these concerns.

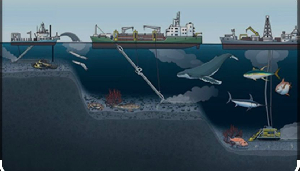

Sea mining refers to the extraction of minerals and metals from the seabed, often located in deep oceanic environments, thousands of meters below the surface. The three primary types of deep-sea mineral resources are:

- **Polymetallic Nodules**: Potato-sized rocks rich in metals like manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper, found on the ocean floor.

- **Seafloor Massive Sulfides (SMS)**: Deposits that form around hydrothermal vents and contain high concentrations of copper, gold, silver, and zinc.

- **Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts**: Found on the slopes and seamounts of underwater mountains, these crusts are rich in cobalt, a key component in batteries.

Deep-sea mining operations are still in the exploratory phase, but technological advancements have made it increasingly feasible to reach these remote areas of the ocean, raising the possibility of full-scale mining in the coming years.

As the world shifts towards green technologies, the demand for key minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium has surged. These materials are essential for renewable energy storage, electric vehicles, and advanced electronics. With land-based mining often limited by environmental regulations, sea mining presents a new frontier for accessing these critical resources.

Many of the minerals required for modern technologies are sourced from regions with high environmental and social costs. Land-based mining can lead to deforestation, soil degradation, and pollution, while also impacting local communities. Sea mining has been proposed as an alternative that could alleviate some of the pressure on terrestrial ecosystems and reduce land-use conflicts.

Countries with exclusive economic zones (EEZs) over resource-rich seabeds could potentially benefit from sea mining. Developing nations in regions like the Pacific and Indian Oceans, home to vast underwater mineral deposits, may stand to gain economically through job creation, technological development, and increased revenues.

Deep-sea mining poses significant threats to marine ecosystems, many of which are poorly understood. The extraction process involves dredging the seabed, which can destroy habitats and disturb fragile ecosystems, including coral reefs and hydrothermal vent communities. Many of these ecosystems are home to unique species that have adapted to the extreme conditions of the deep ocean and could face extinction if their habitats are disrupted.

Mining operations can create large sediment plumes that spread over vast areas of the ocean. These plumes can smother marine life, reduce water quality, and affect the food chains that depend on plankton and other microorganisms. The long-term impact of these sediment disturbances is still largely unknown, but scientists warn of the potential for widespread ecological damage.

Many coastal communities, especially in developing countries, rely on healthy ocean ecosystems for their livelihoods, particularly through fishing. Any disruption to the marine environment caused by sea mining could affect fish populations and biodiversity, which in turn could have serious consequences for food security and local economies.

Unlike land-based mining, deep-sea mining is relatively unregulated. While the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body, is tasked with regulating mineral resources in international waters, many environmentalists argue that current frameworks are insufficient to protect the deep-sea environment. Additionally, individual countries have jurisdiction over mining within their EEZs, but enforcement of environmental protections can vary widely.

A robust regulatory framework is needed to ensure that sea mining is conducted responsibly. The ISA is working to develop a comprehensive set of regulations for mining in international waters, but these need to be finalized and enforced before large-scale operations begin. This framework should include stringent environmental impact assessments, monitoring protocols, and enforceable penalties for violations.

Given the uncertainties surrounding the environmental impacts of sea mining, many scientists and environmentalists advocate for a precautionary approach. This would mean delaying commercial sea mining activities until more is known about the ecosystems involved and the long-term effects of mining on the deep sea.

One potential solution to the environmental risks of sea mining is to invest in alternative technologies for mineral extraction and recycling. Innovations in battery recycling, for example, could reduce the need for new mining operations by recovering valuable minerals from old batteries and electronic waste.

Certain areas of the ocean, such as hydrothermal vents and seamounts, are considered biodiversity hotspots and should be protected from mining activities. Establishing marine protected areas (MPAs) and exclusion zones in key regions can help preserve vulnerable ecosystems and ensure the long-term health of marine biodiversity.

In areas where sea mining is proposed, particularly in developing countries, it is important to engage local communities in decision-making processes. Ensuring that local populations benefit from mining operations while minimizing environmental and social harm should be a priority for governments and companies involved in sea mining.

In conclusion, Sea mining presents both opportunities and challenges for the future. On one hand, it offers the potential to access critical minerals needed for a green economy, but on the other, it poses significant risks to marine ecosystems and the livelihoods of coastal communities. As the race for deep-sea resources accelerates, it is essential that robust environmental safeguards and responsible mining practices are implemented to protect the oceans. Balancing the economic benefits with the need to preserve the marine environment will be key to ensuring that sea mining does not become another source of ecological degradation.

By Prince Agyei Opoku, Cape Coast