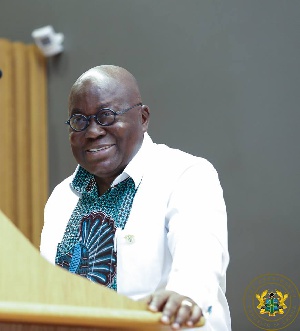

President Akufo-Addo was speaking to students of London School of Economics

President Akufo-Addo was speaking to students of London School of Economics

Chairperson, I thank the organisers for the invitation to come here and participate in this summit. In the short period since I assumed the high office of President of the Republic of Ghana, I will have had the good fortune to address audiences in the three most celebrated institutions of higher learning in this country.

The first was at Cambridge University on 20th November, 2017, where I spoke on “Democracy and Development”. The second is today at the London School of Economics, where I will be speaking on “Africa At Work: Educated, Employed and Empowered.” The third, the icing on the cake, will be when I speak on 11th May at Oxford University. I am, indeed, fortunate.

This place, the London School of Economics, was founded by one of the most remarkable couples of British history – Beatrice and Sidney Webb – who devoted their lives to the betterment of society. Great social reformers, they were leading elements in the massive mobilisation of the early 20th century that brought about significant reforms in British social life. One such was the establishment of this institution, which has played such a notable part in the modern development of Britain.

It holds a special place, too, in the history of our African continent. There is a long list of Africans, who have been through these hallowed halls and gone on to have influence and direct the affairs of their countries. Let me mention just a few: Jomo Kenyatta, Sylvanus Olympio, Kwame Nkrumah, J.H. Mensah, Gilchrist Olympio, Hilla Limann, John Evans Atta-Mills; persons who have all had, in varying degrees, great impact on the development of their countries and of Africa. So, you can see, LSE has become part of Africa’s DNA, and continues to incubate new generations of Africans, who will persevere with the tradition of service and leadership.

This summit has also grown to acquire a formidable reputation, and I am grateful that the organizers decided to make me part of this year’s events. They have chosen the most relevant theme of Africa’s contemporary situation, a theme which sums up the essence of African aspirations – an Africa at work: educated, employed and empowered.

However, the stark truth is that, today, much of Africa is not at work, a large section is uneducated, an alarming proportion is unemployed, and almost all of it feels dependent. I take it, therefore, that your gathering aims to find how we get to this scene of the educated, employed and empowered Africa at work.

I stated somewhere, recently, that it appears the words Africa and Africans have more resonance outside the continent than inside. When we are home on our continent, it always seems very important to assert that we are Ghanaians, Kenyans, Zambians, Swazis, Senegalese, Rwandans, South Africans and, of course, that we are Nigerians, who, we are told, are set soon to number 200 million. Many of us do not want anyone to forget that there are 54 sovereign nations on the continent, with different cultures, languages and rates of development. I pointed out the fact that a bomb explosion in Brussels does not lead to people cancelling trips to Amsterdam, whereas a bomb in Mombasa would trigger a travel advisory to Kampala. In other words, I was saying, perhaps it would be fairer to treat us as 54 sovereign nations, just as the nations of Europe are treated separately.

We have divisions that are linked to our colonial experiences, and indeed, we, the Anglophones, have just finished a successful Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting here in London, and we claim an affinity with each other, that we cannot, at first blush, find with our Francophone neighbours. Then we find ourselves outside the continent, and we discover that, to the outside world, there are no Ghanaians, there are no Senegalese, and there are no Tanzanians, there are Africans, we are all simply Africans.

The lesson is clear: our destinies are intricately linked with each other, and we are talking not only about those of us on the continent, but about the Africans in the diaspora as well. You can be an honour graduate from LSE or any of the other top universities in this country, you can be a second or third generation British, and you can be in a well-paid job; if there is an outbreak of Ebola some place on the African continent, you are an African.

Ladies and gentlemen, so what is this Africa and who are we, what defines us and who defines us? Ours is a continent that is home to some of the most spectacular scenes that nature bestowed on this planet. Our continent has every mineral that mankind lusts after, and which is required to run a modern economy. 30% of the earth’s remaining minerals can be found on the continent. Paradoxically, the African people happen also to be the poorest in the world.

Our continent also has the youngest population, and the biggest pool of unemployed, and our youth, who bear the brunt of the suffering, now resort to desperate measures to get out. They brave the Sahara Desert on foot, and those, who survive the ravages of the desert, risk being sold in slave markets in Libya or risk journeys across the Mediterranean Sea on rickety boats, all in the forlorn hope of a better life in Europe in countries and amongst people where they are obviously not welcome.

To the outside world, therefore, we are defined as that modern entity called an illegal migrant.

Africa has been called many names throughout the ages: dark, beleaguered, a scar on the conscience of the world, hapless, and hopeless are some of the more frequent and colourful ones that can be repeated in decent company, until the recent dramatic intervention of President Donald Trump.

Anyone, everybody in a position of leadership in Africa today, thus, has his work cut out. I do not suggest that we lock up our young people to prevent them embarking on these hazardous journeys.

The urgent responsibility we face is to make our countries and our continent attractive for our youth, to see as places of opportunities. It means we must provide education, quality education and skills training. It means our young people must acquire the skills that run modern economies.

There will always be those among our young people, who would want to try their luck in foreign countries. When they are skilled, they would not have to risk drowning in the Mediterranean Sea, they would be head hunted, and treated with dignity.

A few months back, I was in Dakar, Senegal to attend a special conference called to raise monies to fund education in Africa. I said it there and it bears repeating here, there is or maybe I should say, there should be enough money in Africa to be enable us pay for educating and training our young people, and make them ready to compete and face the world.

Where is this money, I hear you ask? As a start, I refer to the report of the panel, chaired by the highly respected former South African President, Thabo Mbeki, on the illicit flow of funds (IFFs) from Africa, which has raised the lid on what many had always suspected, but did not have the figures to support.

According to the report, Africa is losing, annually, more than $50 billion through illicit financial outflows. The report revealed further that, between 2000 and 2008, $252 billion, representing 56.2%, of the illicit flow of funds from the continent, was from the extractive industries, including mining. The dispiriting part of the story, of course, is the fact that some Africans are complicit for taking these monies out of our countries, and into western countries.

But the majority of it is spirited out by those who come, claiming to do business with us. It is clear that we are not well equipped to cope with those who come to conduct business in our countries, with the aim of making extraordinary returns through unorthodox and illegal means.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is obvious that no one is going to sort out these matters for Africa, except Africans themselves. We must match those who come to do business with us in all the skills they possess. We must have our own set of bright and sharp lawyers, our own set of bright and sharp accountants to keep us abreast with the sharp and bright lawyers and accountants that our trade partners have. In much the same way, we need to have our own bright and sharp technologists to keep us abreast with our competitors.

Some investors always find innovative ways to avoid paying the taxes that they should in the African countries, in which they operate.

It is in these areas that it becomes obvious that there is great advantage in African countries operating together as a block, rather than as individual countries. As our elders say, there is strength in unity.

It has been shown that countries or groups of countries with the largest share of world trade are located within regions with the highest share of intra-regional trade. Trade between African countries remains low, compared to other parts of the world. In 2000, intra-regional trade accounted for 10% of Africa’s total trade, and increased marginally to 11% in 2015. Trading amongst members of the European Union, for example, amounted to 70% in 2015. With Africa’s population set to reach some 2 billion people in 20 years’ time, an African Common Market presents immense opportunities to bring prosperity to our continent and its longsuffering peoples with hard work, creativity, ingenuity, innovation and enterprise. We made a significant start, a few weeks ago, when, on 21st March, 2018, close to 50 member states of the African Union signed the Continental Free Trade Area Agreement in Kigali, in Rwanda.

The free trade area will succeed as we transform the structure of our economies from economies that are dependent on the production and export of raw materials to value-adding economies, with a modernised agriculture, which enables us not only to feed ourselves, but also to generate the thousands and thousands of jobs that our young people need. Trade, then, is made on the basis not of raw material exports, but on the basis of things we make. That is the surest route to prosperity, widespread employment and enhanced incomes.

For this free trade area to be viable, there must be peace and stability on the continent. Nothing undermines the prospects of our continent more than being known as unstable, and, unfortunately, our politics has been the main source of the spark for instability.

I know I have to tread gingerly here, lest I come across as preaching to anyone on this particular subject. I would only say that we, in Ghana, having tried everything else, have finally reached a consensus that a multi-party system of governance works best for us. Our 4th Republic has lasted for 25 years under a multi-party Constitution, the longest, uninterrupted period of stable, constitutional governance in our hitherto turbulent history. We are stable, and there have been three peaceful changes of government from a ruling party to an opposition party. Principles of democratic accountability, respect for human rights and the rule of law, are now firmly entrenched in our body politic, and are helping to promote accountable governance.

It is still early days, but our institutions are growing and the self-confidence of the people is becoming manifest. I dare say that we are even beginning to accept that a political party can lose an election with grace, and serve with honour in opposition.

The greatest challenge for us in Ghana, and for the entire continent, remains the creation of sustainable jobs.

The African Union’s Agenda 2063, titled The Africa We Want, calls for an education and skills revolution to meet the human resource needs for inspiring Africa’s socio-economic development. The African Union has, quite correctly, placed high premium on science, technology and innovation as critical ingredients to the achievement of Agenda 2063. All over the world, governments encourage universities to promote technological advancement by investing public funds into research and development (R&D), and stimulate linkages between academia and the private sector.

We still have a lot of work to do to in these areas. It is time, ladies and gentlemen, to encourage our researchers to think big, and for governments to offer the incentives and extend the protection they need for their inventions.

Another important sub-theme, which is also critical to our sustainability as a continent, is graduate employability. Studies have shown that investment in human resource is one venture that yields the maximum benefit to any nation. According to the ‘State of Education in Africa Report 2015’, published by the Africa-America Institute, returns on investments in higher education in Africa is 21 percent—the highest in the world. While this is good news for us, as a continent, we should face the very unpleasant fact that, for many of our graduates, a university education no longer guarantees a job.

We need to make sure that the curricula we offer are relevant to the skills needs of the job market. Our products should have transferable skills, to enable them cope with the realities of the modern-day world of work, which has embraced the digital revolution. In current global dispensations, where universities are becoming entrepreneurial to remain relevant, our universities have to engage more with the private sector.

The African Union’s Agenda 2063 has laid out clear implementation strategies, namely the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA-2025) and the Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa (STISA-2024), as well as the renewed focus on Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). In Ghana, my government has aligned all TVET institutions, which were previously being managed by 19 different public entities, under the Ministry of Education, to provide for better co-ordination of their curricula and more effective training.

Ladies and gentlemen, the provision of education for our young people should not become an ideological tussle. We should never have to make a choice between basic education or higher education. We should never have to rely on the World Bank or any other institution to decide for us where the emphasis should be in our education needs. Education is the key to our development, and we must run our economies to be able to fund the education of our children. We should not get into arguments with donor agencies about our priorities. We must set our own priorities, and we must accept that we should provide the funds to translate our plans into reality. That is why, despite the bleak economic situation my government inherited, we decided to implement immediately the pledge we had made about providing Free Senior High School education. The most dramatic aspect of its implementation has been that 90,000 more students entered senior high school in September last year, the first term of the policy, than in 2016.

Again, we are reviving the strength of our National Health Insurance Scheme, which, under the previous administration, was being strangled by debt. Of the GH¢1.2 billion debt we inherited, the equivalent of $300 million, we have paid, in the last 15 months, GH¢1 billion, the equivalent of $250 million, and payments to service providers are now current. The Scheme is regaining its effectiveness so that for a minimum amount, subscribers can have access to a wide range of medical services.

We have done enough talking, and, dare I say, we have had enough conferences and workshops. We know what we need to do. It is time just to do it. We have run out of excuses for the state of our continent. We have the manpower, we should have the political will, it is time to make Africa work.

There might be 54 countries, and we might sometimes resent being lumped together for the wrong reasons, but there are strong ties that bind us together as Africans.

We have good reasons to be proud of who we are, and the beautiful continent that is ours. The geographic space covered by Africa makes it the second largest of the seven continents. It has some of the most breath-taking scenes on our planet. It has plants and animals that are wonders of the world, and critical for the survival of the planet.

I hear a lot about the need to change our narrative and tell our own good stories. Ladies and gentlemen, as the saying goes, nothing succeeds as much as success.

If we work at it, if we stop being beggars, and spend Africa’s monies inside the continent, Africa would not need to ask for respect from anyone. We would get the respect we deserve. Over thirty years ago, Princeton University, one of America’s most prestigious Ivy League Universities, offered a course in Mandarin, which, for years, had virtually no takers. Today, there is standing room only. And it is not because the course is any easier, it is because the position of China has changed. Thirty years ago, twenty years ago, China was nowhere near where it is today. China does not ask anyone for respect now, she does not need to.

We have a responsibility to take care of our environment. We have the most spectacular natural surroundings, grandest of rivers and mountains. We have a dynamic and young population. Yes, we have music that reaches the soul. We bring humanity alive. Let us make our continent the prosperous and joyful place it should be. We would get the respect we deserve.

Our young people must see and feel the dividends of the democratic system of governance. In Ghana, whereas the indications are that the economic dividends are on the horizon, there are other areas where we are thriving.

The media in Ghana has come into its own, and what used to be called the culture of silence has been replaced with a cacophony that now worries some. I have said it before, and I believe it bears repeating, I would much rather put up with a reckless press than a monotonous, praise-singing one.

A democracy has no place for a media that does not keep public authorities on their toes. I acknowledge that we are all still trying to keep pace with the changing technology, and work out how we deal with social media, and, dare I say it, the phenomenon of fake news. (I shall not say more on that, and leave it to those more knowledgeable on that subject).

But I am a firm believer in a strong and vibrant media, and I have no doubt that it is a force for good, no matter how irritating and how irksome they can be and often are. They provide the avenue for the other point of view.

Our success story and changed narrative come with building our economies that are not dependent on charity and handouts.

Then we shall put an educated, employed and empowered Africa to work, and repudiate the recent culture of failure. We shall then take our rightful place in the world.

May God bless us all, and Mother Africa, and make her great and strong. Once again, many thanks for the invitation, and thank you very much for your attention.