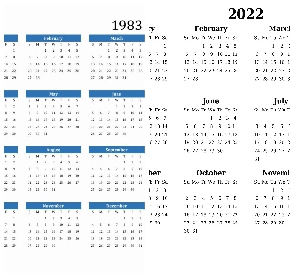

Photo of the 1983 and 2022 calenders

Photo of the 1983 and 2022 calenders

To say ‘times are hard’ in Ghana now will only be stating the obvious, and for President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo to have confirmed the same only reaffirms the fact that the country is faced with very trying times. From the crumbling Ghana cedi against foreign currencies like the United States dollar to the ever-rising prices of fuel, the soaring food prices and general standards of living, truly, the country is not in normal times. In his words, President Akufo-Addo has assured Ghanaians that he will turn things around just as, he added, he has done before. “For us in Ghana, our reality is that our economy is in great difficulty. “We are in a crisis; I do not exaggerate when I say so. I cannot find an example in history when so many malevolent forces have come together at the same time,” excerpts of his address to the nation on Sunday, October 30, 2022, read. But while the president sought to indicate that there has never been a time in history where so many forces have come together to affect the country, there actually has been such a time before. In fact, in that ‘such a time,’ when Ghana experienced one of its toughest economic downturns, it has emerged that there are some spooky similarities between those two years: 1983 and 2022. It has emerged that the same calendar used in 1983 is the same calendar that is currently being used in the year 2022. For more clarity, if you look at the calendar of 1983 and 2022, it is the same thing. Even more interesting is the fact that 1983 in Ghana was a time of a great food drought, while in 2022, the country is experiencing harsh economic difficulties. A mere case of coincidence? Well, let’s look at the striking similarities between these two years that history appears to be repeating. About the 1983 drought in Ghana: The following description of what happened in 1983 was written by Kwasi Gyan-Apenteng and first published on GhanaWeb on May 13, 2013. The year 1983 perhaps was the harshest year in Ghana’s modern history. The year 1983 did not start well. One of the harshest droughts was in progress. There had been little meaningful rain since 1981; that is, it has either rained little or the rain had come at the wrong place and time. The drought could not have come at the worst possible moment. To understand the full import of what happened, a bit of history is in order. The most unsettled decade for this country has to be the 1970s, the years during which, for good or ill, the chickens of the Nkrumah overthrow in 1966 came home to roost. Maybe the Progress Party government of Dr. Kofi Abrefa Busia could have succeeded in its policy of rural development, but we have no way of knowing because it lasted only 27 months. In the meantime, it managed to sell off state assets in a manner that foreshadowed other economic controversies, some would say disasters, in the following decades. In January 1972, Colonel Kutu Acheampong and his close friends staged a military coup and took over the country. They did not appear to have any development strategy, but they managed to infuse a sense of purpose and urgency around their slogan of “Operation Feed Yourself” and a mild form of pan-Africanism and Nkrumaist orientation, later to be described as “domestication” by the late Dan Lartey who was one of their civilian advisers. In 1975, Acheampong’s closest comrades in their National Redemption Council government were demoted to a second tier of government in a palace coup staged by the most senior officers in all branches of the military. They formed the Supreme Military Council, still with Acheampong as head but without the esprit de corps he enjoyed with his demoted friends, who quietly left the centre stage of government. The SMC had no policies except staying in power through some of the most disastrous economic crises we have ever known. This article is not the place to go into the details of those policies and their consequences, except to remind us that almost all sections of society rose up against the government. Trapped and with nowhere to go, the SMC tried one last trick; this was the “Union Government” (UNIGOV), an ill-defined coalition of civilians, soldiers and police officers. A botched referendum was the last straw, and yet another palace coup overthrew Acheampong in 1978 and replaced him with General F.W.K. Akuffo, who was generally acknowledged to be a first-class military officer but untested as a political leader. He is the man who used military discipline and precision to lead Ghana’s switch from driving on the left to the right in 1974 without a single accident on the day of the change. However, his attempts, first to continue the UNIGOV scam under a different guise and then absolve the military of blame, did not sit well with soldiers and civilians. On June 4 1979, a fortnight before the first general elections in a decade, a group of young soldiers overthrew the Akuffo government as they successfully released a certain Air force officer from custody at the Special Branch headquarters where he had been held since leading a failed insurrection on May 15 that year. That young air force officer, of course, was Flt Lt. Jerry John Rawlings, who needs no introduction in this discussion. On the last day of the year 1981, Rawlings, who had retired from the military, led another insurrection to overthrow the Limann-led Peoples National Party government, which had been in office since the Rawlings insurrectionist gave up power three months after their coup. Flt Lt Rawlings announced at the beginning of his insurrectionary regime that it was a “revolution”, and the revolution’s first year saw the country economically destabilised partly by the revolutionaries’ own activities and by international pressure. Squeezed by international commercial lenders, Ghana’s credit dwindled and disappeared. Our credit was not a lot to start with; Nigeria had to bring in truckloads of gifts, including toilet rolls, to soften our difficulties during Christmas! Understandably, life got very difficult for most citizens of this country. In the meantime, as the lack of raw materials shut local production of everything, we could make ourselves there was no money to import anything and yet warehouses had been emptied by revolutionaries pursuing social justice. The revolutionaries had a point, even if it was excessively expressed. Ghana could not continue on the path, whichever it was, that had driven us that far. The nation needed restructuring, and whether a political revolution was the ideal way to perform this all-out change in those circumstances still needs to be debated in this country. There is a Japanese proverb that says, “although the sign reads, do not pluck these flowers from this garden, it is useless against the wind which does not read”. The drought did not read the revolutionary script and deepened as 1982 turned into 1983. There had been little notice in the Ghanaian media that Nigeria had given a very strict and final ultimatum in 1982 to foreigners there to “regulate” their stay or be kicked out early in 1983. It is difficult not to conclude that Nigeria’s actions were in some way retaliation for Ghana’s own eviction of foreigners, mostly Nigerians, some fourteen years earlier. More than one million Ghanaians had to pack bags and baggage and head home. They came into an empty country. Food was scarce and disappearing fast, and although our “returnees” came with some nicely painted bags known as “Ghana Must Go” and many stories of atrocities, none brought a morsel of food to add to the national stock. Ghana at present: The government of Ghana has routinely explained that recent economic headwinds are attributable largely to the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the banking sector clean-up. The rippling effect has been an increase in the cost of living, high inflation rates and downgrades of the economy by rating agencies such as S&P and Fitch – a situation which has dealt a heavy blow to government’s ability to access the international capital market. The Cedi has also been on a free fall compelling the Bank of Ghana to resort to hiking its monetary policy rate to deal with the situation. The worsening economic situation compelled the government in July to initiate contact with International Monetary Fund for an economic support programme. Ghana is targeting an amount of US$3 billion over three years from the Fund once an agreement on a programme is reached. Government hopes to complete negotiations by the end of this year in order to receive the funds in the first quarter of 2023. Find below the calendars of 1983 and 2022: AE/WA

To say ‘times are hard’ in Ghana now will only be stating the obvious, and for President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo to have confirmed the same only reaffirms the fact that the country is faced with very trying times. From the crumbling Ghana cedi against foreign currencies like the United States dollar to the ever-rising prices of fuel, the soaring food prices and general standards of living, truly, the country is not in normal times. In his words, President Akufo-Addo has assured Ghanaians that he will turn things around just as, he added, he has done before. “For us in Ghana, our reality is that our economy is in great difficulty. “We are in a crisis; I do not exaggerate when I say so. I cannot find an example in history when so many malevolent forces have come together at the same time,” excerpts of his address to the nation on Sunday, October 30, 2022, read. But while the president sought to indicate that there has never been a time in history where so many forces have come together to affect the country, there actually has been such a time before. In fact, in that ‘such a time,’ when Ghana experienced one of its toughest economic downturns, it has emerged that there are some spooky similarities between those two years: 1983 and 2022. It has emerged that the same calendar used in 1983 is the same calendar that is currently being used in the year 2022. For more clarity, if you look at the calendar of 1983 and 2022, it is the same thing. Even more interesting is the fact that 1983 in Ghana was a time of a great food drought, while in 2022, the country is experiencing harsh economic difficulties. A mere case of coincidence? Well, let’s look at the striking similarities between these two years that history appears to be repeating. About the 1983 drought in Ghana: The following description of what happened in 1983 was written by Kwasi Gyan-Apenteng and first published on GhanaWeb on May 13, 2013. The year 1983 perhaps was the harshest year in Ghana’s modern history. The year 1983 did not start well. One of the harshest droughts was in progress. There had been little meaningful rain since 1981; that is, it has either rained little or the rain had come at the wrong place and time. The drought could not have come at the worst possible moment. To understand the full import of what happened, a bit of history is in order. The most unsettled decade for this country has to be the 1970s, the years during which, for good or ill, the chickens of the Nkrumah overthrow in 1966 came home to roost. Maybe the Progress Party government of Dr. Kofi Abrefa Busia could have succeeded in its policy of rural development, but we have no way of knowing because it lasted only 27 months. In the meantime, it managed to sell off state assets in a manner that foreshadowed other economic controversies, some would say disasters, in the following decades. In January 1972, Colonel Kutu Acheampong and his close friends staged a military coup and took over the country. They did not appear to have any development strategy, but they managed to infuse a sense of purpose and urgency around their slogan of “Operation Feed Yourself” and a mild form of pan-Africanism and Nkrumaist orientation, later to be described as “domestication” by the late Dan Lartey who was one of their civilian advisers. In 1975, Acheampong’s closest comrades in their National Redemption Council government were demoted to a second tier of government in a palace coup staged by the most senior officers in all branches of the military. They formed the Supreme Military Council, still with Acheampong as head but without the esprit de corps he enjoyed with his demoted friends, who quietly left the centre stage of government. The SMC had no policies except staying in power through some of the most disastrous economic crises we have ever known. This article is not the place to go into the details of those policies and their consequences, except to remind us that almost all sections of society rose up against the government. Trapped and with nowhere to go, the SMC tried one last trick; this was the “Union Government” (UNIGOV), an ill-defined coalition of civilians, soldiers and police officers. A botched referendum was the last straw, and yet another palace coup overthrew Acheampong in 1978 and replaced him with General F.W.K. Akuffo, who was generally acknowledged to be a first-class military officer but untested as a political leader. He is the man who used military discipline and precision to lead Ghana’s switch from driving on the left to the right in 1974 without a single accident on the day of the change. However, his attempts, first to continue the UNIGOV scam under a different guise and then absolve the military of blame, did not sit well with soldiers and civilians. On June 4 1979, a fortnight before the first general elections in a decade, a group of young soldiers overthrew the Akuffo government as they successfully released a certain Air force officer from custody at the Special Branch headquarters where he had been held since leading a failed insurrection on May 15 that year. That young air force officer, of course, was Flt Lt. Jerry John Rawlings, who needs no introduction in this discussion. On the last day of the year 1981, Rawlings, who had retired from the military, led another insurrection to overthrow the Limann-led Peoples National Party government, which had been in office since the Rawlings insurrectionist gave up power three months after their coup. Flt Lt Rawlings announced at the beginning of his insurrectionary regime that it was a “revolution”, and the revolution’s first year saw the country economically destabilised partly by the revolutionaries’ own activities and by international pressure. Squeezed by international commercial lenders, Ghana’s credit dwindled and disappeared. Our credit was not a lot to start with; Nigeria had to bring in truckloads of gifts, including toilet rolls, to soften our difficulties during Christmas! Understandably, life got very difficult for most citizens of this country. In the meantime, as the lack of raw materials shut local production of everything, we could make ourselves there was no money to import anything and yet warehouses had been emptied by revolutionaries pursuing social justice. The revolutionaries had a point, even if it was excessively expressed. Ghana could not continue on the path, whichever it was, that had driven us that far. The nation needed restructuring, and whether a political revolution was the ideal way to perform this all-out change in those circumstances still needs to be debated in this country. There is a Japanese proverb that says, “although the sign reads, do not pluck these flowers from this garden, it is useless against the wind which does not read”. The drought did not read the revolutionary script and deepened as 1982 turned into 1983. There had been little notice in the Ghanaian media that Nigeria had given a very strict and final ultimatum in 1982 to foreigners there to “regulate” their stay or be kicked out early in 1983. It is difficult not to conclude that Nigeria’s actions were in some way retaliation for Ghana’s own eviction of foreigners, mostly Nigerians, some fourteen years earlier. More than one million Ghanaians had to pack bags and baggage and head home. They came into an empty country. Food was scarce and disappearing fast, and although our “returnees” came with some nicely painted bags known as “Ghana Must Go” and many stories of atrocities, none brought a morsel of food to add to the national stock. Ghana at present: The government of Ghana has routinely explained that recent economic headwinds are attributable largely to the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the banking sector clean-up. The rippling effect has been an increase in the cost of living, high inflation rates and downgrades of the economy by rating agencies such as S&P and Fitch – a situation which has dealt a heavy blow to government’s ability to access the international capital market. The Cedi has also been on a free fall compelling the Bank of Ghana to resort to hiking its monetary policy rate to deal with the situation. The worsening economic situation compelled the government in July to initiate contact with International Monetary Fund for an economic support programme. Ghana is targeting an amount of US$3 billion over three years from the Fund once an agreement on a programme is reached. Government hopes to complete negotiations by the end of this year in order to receive the funds in the first quarter of 2023. Find below the calendars of 1983 and 2022: AE/WA