The name refers to a leak of 13.4m files. Most of the documents – 6.8m – relate to a law firm and corporate services provider that operated together in 10 jurisdictions under the name Appleby. Last year, the “fiduciary” arm of the business was the subject of a management buyout and it is now called Estera.

here are also details from 19 corporate registries maintained by governments in secrecy jurisdictions – Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the Cook Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Labuan, Lebanon, Malta, the Marshall Islands, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent, Samoa, Trinidad and Tobago, and Vanuatu.

The papers cover the period from 1950 to 2016.

The transfer of wealth

The customers

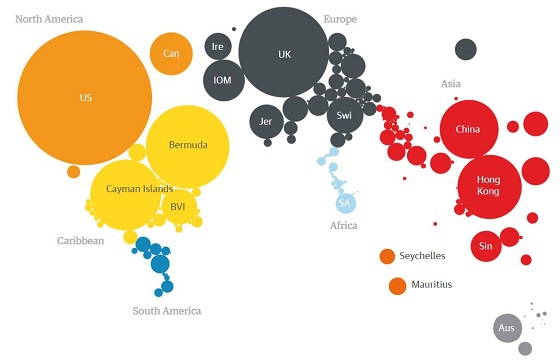

Money flows into the offshore world from everywhere. It's often very hard to identify the people and companies behind it. Among the documents in the leak is a database of Appleby customers from 1993 to 2014. It contains the names of more than 120,000 people and companies. Not all are connected to a company registered offshore.

It has been an impossible task to check whether the customer is just a contact or if they have used Appleby services over many years. But it gives a good indication of where demand for Appleby’s services originated. Many clients come from the UK, China and Hong-Kong, but the largest number, more than 30,000, are from the US.

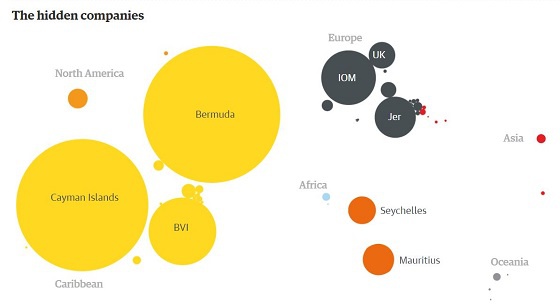

Companies registered offshore can be used to hold assets such as property, aircraft, yachts and investments in stocks and shares. The Appleby data records about 25,000 offshore companies. The most popular jurisdictions for incorporations were the British-ruled tax havens of Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. The British Virgin Islands, another UK overseas territory, and the Isle of Man, which is a British crown dependency, were also popular with Appleby clients.

How many media organisations have been looking at the data?

The Guardian is one of 96 media partners in the project. A total of 381 journalists from 67 countries have been analysing the material.

Who got the documents – and how?

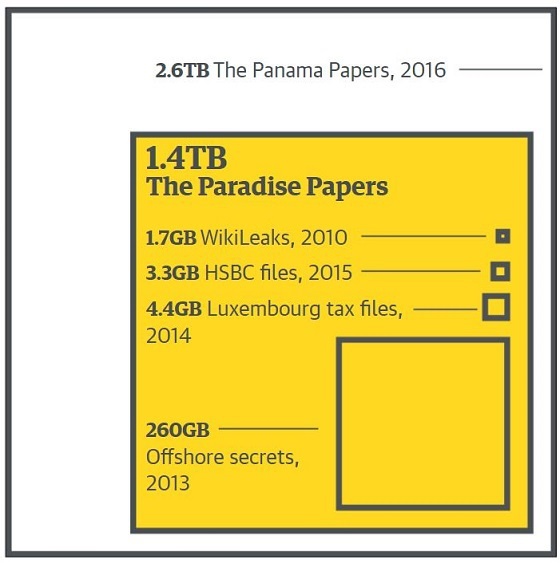

The leaks were obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which also received the Panama Papers last year. Süddeutsche Zeitung shared the material with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a US-based organisation that coordinated the global collaboration. Süddeutsche Zeitung has not, and will not, discuss issues around sourcing.

The world’s (second) biggest data leak

Do the Paradise Papers focus on companies or individuals?

Both. They are united by one thing – money. Some of the world’s biggest multinationals feature in the leak, including Apple, Nike and Facebook, as well as some of the richest people in the world, from the Queen to Bono, and from the stars of British sitcoms to the stars who grace Hollywood Boulevard.

What do the documents show?

The files show the offshore empire is bigger and more complicated than most people thought. And even companies such as Appleby, which prides itself on being a standard bearer in the field, have fallen foul of the regulators that try to police the industry.

The files set out the myriad ways in which companies and individuals can avoid tax using artificial structures. These schemes are legal if run correctly. But many appear not to be. And politicians around the world are beginning to ask whether they should be banned. Are they fair? Are they moral? A fundamental question posed by the Paradise Papers is: has tax avoidance in all guises gone too far?

Key revelations include: