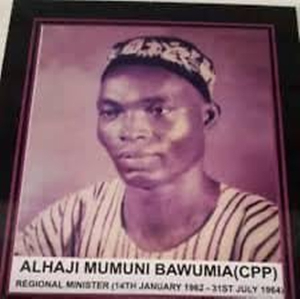

An old photo of Alhaji Dr Mumuni Bawumia when he was still with the CPP

An old photo of Alhaji Dr Mumuni Bawumia when he was still with the CPP

Alhaji Mumuni Bawumia belongs to the first generation of national politicians in northern Ghana after the Protectorate of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast was merged with Ashanti and the Gold Coast Colony. The British crafted the Gold Coast as a tripartite administration of distinct and separate but contiguous territorial entities.

By 1902, the Gold Coast comprised the Gold Coast Colony along the coastal belt, the Colony of Ashanti and the Protectorate of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast.

The littoral colony and Ashanti were united in 1946 and the Northern Territories joined the union in 1951. The British Trust Territory of Togoland, the western portion of the former German Protectorate of Togo which was partitioned between Britain and France when Germany was defeated in the First World War, was initially administered as an integral part of the Gold Coast and the two territories became Ghana on 6 March 1957.

Alhaji Mumuni Bawumia was born into a royal family of the large and important Mamprugu traditional area in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (now northern Ghana) in January 1924. His father was a chief and had to throw a son away to the white man for schooling or lose his skin and the lot fell on Mumuni by default. At that time chiefs were compelled to send their children to school and most of such pupils later became chiefs themselves.

Young Mumuni started primary education at Gambaga in May 1934 when the school fees were thirty shillings per year. The principal teacher was J.B. Haruna, one of the few teachers of northern extraction who were trained at the Accra Teacher Training College and later at Achimota College. Mumuni Bawumia was promoted twice in the primary school and he gives a brief and vivid description of the conditions under which he schooled at Gambaga and remarks that “such conditions hardened us, created in us the spirit of duty consciousness and, above all, a sense of discipline and punctuality” (p. 7). These attributes are sadly lacking in the educational system in Ghana today. The conditions of schooling portrayed in this book were applicable to all pupils in the Northern Territories. The training received at this stage was to be of tremendous value in his later life.

In 1940, Mumuni Bawumia was admitted to Standard Four at the only Middle Boarding School at Tamale. The School was the highest educational institution in the Northern Territories and served what are currently the Northern, Upper East and Upper West Regions and the former Krachi District now in the Volta Region. It was not until 1947 that a Middle Boarding School for girls was established at Tamale. There was very keen competition among the fortunate pupils from the various primary schools in the Protectorate and the Krachi District. Some of Bawumia’s classmates were S.D. Dombo, Abayifaa Karbo, B.K. Adama and Polkuu Konkuu. Bawumia and some of his classmates later co-operated with others to form the Northern Peoples Party with Dombo as the leader.

Standard Seven was the highest grade a student could attain, and Northerners were barred from attending Secondary Schools in the South (Bening 1990: 160-169). The Northern Territories had been set up as a separate education area in January 1927, after Governor Guggisberg visited the Wa primary school and declared that the standard of education provided was too high, and should be limited to Primary Six for the generality of the population and only the best students should be allowed to reach Standard 7.

However, a few specially selected pupils were sent to Accra Teacher Training College and later to Achimota College to train as teachers to replace Southerners in the schools (Bening 1990: 52-55). The rest who obtained the Standard Seven Certificate were sent to be Native Authority clerks, agricultural instructors and sanitary overseers.

Mumuni Bawumia took the final Standard Seven Examination in December 1943, with Alhassan Gbanzaba, who became the first person from northern Ghana to obtain a degree from the University of Cambridge in the U.K., as the class teacher. Talented Mumuni offered to be a teacher in expectation that he would be among the few students to be sent for training at Achimota College.

However, the government released a statement that “was more than a bombshell and dashed all our hopes for further studies” (p.10). It was announced that “Government had changed its policy and that henceforth Northerners were not going to be allowed to further their studies in Southern Ghana and this was also to be the case with Teacher Training” (p.10). A Teacher Training College was opened at Tamale in 1944 for male teachers. Only Susana Henkel (later Mrs Susana Alhassan), who opted to be a teacher, was sent to Achimota for teacher training.

As the reasons for the decision to train teachers locally have not been given, it is important to state them here briefly. Colonial policy from the onset aimed at isolating the North from the rest of the country in order to bolster the power of the chiefs and instil into the minds of the people “a sense of their obligations before the pernicious doctrine of individual irresponsibility filters through from the coast native” (Bening 2005: 39). The political activities of the educated elite in the South had created all sorts of problems for the colonial administration and when some of the Achimota trained teachers began to question the policies pursued in the North, it was time to train teachers locally and cut off the evil influences from the South in order to facilitate indirect rule or native administration (Bening 1990: 120-125).

Bawumia’s ambition to train at Achimota was thus curtailed. Although he had been accepted as a teacher, he was posted in January 1944 to Bawku to relieve the Town Clerk, who wished to be among the first batch of students to enter the Tamale Training College. However, he was called upon to teach at the Gambaga Primary School in March of the same year because of the shortage of teachers. He was admitted to the Tamale Training College in 1945 and was awarded the Teachers Certificate “B” at the end of 1946. He supervised the construction of the Kpasenkpe Primary Day School which he opened in 1947, using the knowledge of carpentry and masonry acquired at the Tamale Training College. One of the first pupils in the school is Prof. J.S. Nabila, who is now Wulugunaba (Paramount Chief of Kpasenkpe Division of Mamprugu). Bawumia went back to Tamale and obtained the Certificate “A” in December 1949 and returned to teach at the Middle Boarding School at Nalerigu, the seat of the Nayiri, the King of Mamprugu.

Bawumia has provided a brief but incisive first hand account of education in northern Ghana which contradicts a popular but erroneous belief that education in the North had been free from colonial times. Parents paid some fees in cash or kind and the Native Authorities, which were established in 1932, took over this responsibility in their effort to expand education so that the people of the Northern Territories would take their proper place in a united Gold Coast. Mumuni Bawumia later addresses the issue of education in northern Ghana during the transition to independence and thereafter, as well as the roles his generation played in the development of the North.

Mumuni Bawumia sought appointment as State Secretary of the Mamprusi Native Authority (NA) after he had failed to convince some of his seniors to apply for the position. His accession to the post portrayed the wisdom of the then Nayiri, Paramount Chief of Mamprugu, in his relations with the colonial officials and in dealing with local politics. He later became Secretary to the Nayiri and Clerk of the Mamprusi District Council in 1952. Mumuni Bawumia has outlined his

Research Review NS 23.1 (2007) 57-67 contributions to the improvement of education in the Mamprusi NA and in the resolution of the land dispute between the Nayiri and the Sandemanaba in the Kpasenkpe Division of Mamprusi state. As the disputed area was inaccessible from Kpasenkpe during the rainy season, Bawumia quickly constructed a motorable road to the area and built a school and a health post at Kunkwa to serve the area isolated by the White Volta River. He also secured the services of Nii Amaa Ollenu to represent the Nayiri in the land dispute. The Sandemanaba, Paramount Chief of the Builsa who inhabit an adjoining area, lost the case and the appeal to the West African Court of Appeal was dismissed in 1952.

The traditional practices of the Mamprusi regarding the burial of chiefs are briefly mentioned, as well as Bawumia’s refusal to succeed his father in favour of a senior brother. The operations of the Mamprusi Native Authority, the largest in the country and the wealthiest in the North, are also outlined. He touches on other important issues: the location of facilities and politics and the beginning of the dissolution of Nayiri’s empire. Bawumia had decided to place a school at a central location at Tinguri. However the head chief at Gbani objected and demanded that it be sited in his town but the idea was resisted. A detailed and interesting account of how the Baptist Mission Hospital was sited at Nalerigu is also provided. As the Mamprusi District Council was a stronghold of the Northern Peoples Party (NPP), J.H. Alhassani, the Minister of Health, and a northern member of the Legislative Assembly representing Dagomba East Constituency, objected to Nalerigu and the Prime Minister had to be contacted. To Alhassani’s dismay Kwame Nkrumah approved the choice of Nalerigu and stated that if the people were not members of the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) they could join the party in future (pp.32-34).

Sections of the royal family of Mamprugu had moved out and established enclaves among the surrounding ethnic communities in what is now the Upper East Region of Ghana and beyond. They superintended the routes of the lucrative trans-Saharan caravan trade. The Mamprusis who settled at the important market centres such as Bawku in the Kusasi area, at Zuarungu among the Frafras and in other areas retained their links with Nalerigu, the seat of the Nayiri, the King of the Mamprusis. Zuarungu and Bawku, a border town strategically located in relation to Togo and Burkina Faso, were made administrative capitals in 1910 and 1909 respectively (Bening 1975a: 652-657).

In 1912 the British colonial administration installed the Nayiri as the Paramount Chief of the whole of the North-Eastern Province, then comprising the areas occupied by the Mamprusis, Kassenas, Frafras, Nankanis, Builsas, Kusasis and other groups. The policy of consolidating ethnic groups into large and viable units of native administration or indirect rule with a hierarchy of chiefs culminated in the formation of the North-Eastern Province into the Mamprusi Native Authority in 1932. However, the persistent and intensive agitation of the Kassenas and Builsas against the hegemony of the Nayiri led to their separation from the Mamprusi NA and District in July 1940 (Bening 1975b: 118-131).

The Nayiri with whom Bawumia worked, Naa Sheriga, was a sagacious ruler who was able to maintain the integrity of the Mamprusi Kingdom. He chose the name Sheriga, meaning needle, because he “likened his kingdom to pieces of cloth and promises to sew these pieces of cloth together into a united garment. His desire was to bring more unity to Mamprusi than it had ever been” (p.37). For Naa Sheriga to achieve his aim he had to, among other things, risk his own life by going against custom and installing a left-handed person as chief in 1951 because he strongly believed that “it was only by making Awuni the Bawkunaba that there would be peace and harmony in the Bawku District” (p.38). When Awuni Saa died, Naa Sheriga installed the obvious choice, Yiremea, as Bawkunaba in June 1957. However, the Nayiri warned Bawumia and a close elder that “after his enskinment we shall struggle for over seven long years before peace could return to Bawku” (p.39). It is interesting to note that Alhaji Bawumia’s first wife is a niece of Yiremea, but he probably had no say in the decision-making process. The enskinment of Yiremea was the immediate cause that sparked the Kusasi - Mamprusi conflict because of certain careless statements about “how we would treat the Kusasis” that were attributed to him. Indeed, permanent peace has eluded the people of the Bawku district for a long time.

The final stages of the disintegration of what remained of the Mamprusi empire after the secession of the Builsas, Kasenas and Nankanis had set in with the introduction of the multi-party system of government in 1951 and the expansion and development of education in northern Ghana.

Some detailed information on what is popularly called the “Bawku Problem” relating to Mamprusi-Kusasi relations would have been interesting, but this was not the making of Bawumia and he decided, as an experienced politician, to stay out of it. He was probably also unaware of Yiremea’s statements that infuriated the Kusasis.

A proposal by Bawumia to upgrade the Palace for all future Nayiris was rejected by Naa Sheriga as the two gates1 each had a particular site for their palaces, even though they were direct descendants of Naa Salifu. Mumuni Bawumia was advised that his proposal would be regarded as an attempt to close the other gate and “if there was no money to reconstruct the two palaces simultaneously in permanent structures,” he should abandon the idea (p.43). Some traditional areas in northern Ghana may profit from the wisdom of Naa Sheriga. Bawumia comes out as a simple, respectful and honest young man in his dealings with the chiefs, employees and people of the Mamprusi District Council, and this partly accounted for the strength of the NPP in the area.

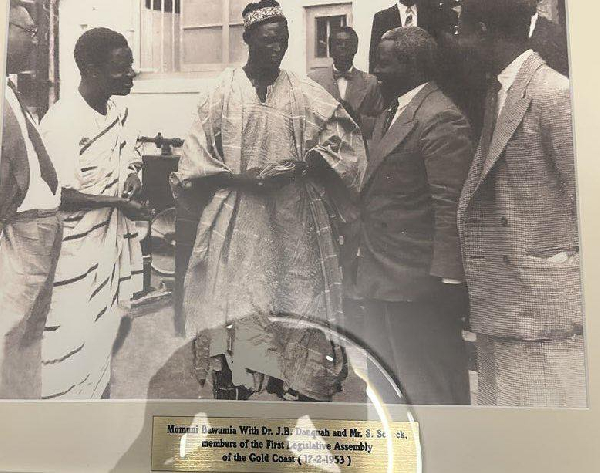

Chapters 4 to 7 deal with the transition to independence, a well-researched period (Austin 1964; Ladouceur 1979), but the role played by the author at the regional and national levels has thrown up a few new facts. He provides a vivid picture of the state of Northern Ghana then as a result of the deliberate policy which aimed at keeping the people as hewers of wood and drawers of water for their compatriots in southern Gold Coast. The Northern Territories Council (NTC), established in 1946, and the Northern Peoples Party (NPP), which was formed in 1954, had similar aims. They championed the cause of the protectorate, urging government to ensure the development of the area to a respectable level before the attainment of political independence. Mumuni Bawumia became a member of the NTC in 1952 and was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1953.

A statement by J.H Allassani, one of the 19 members from the North in the Legislative Assembly, in 1951, supports the statements of Bawunia in his memoirs in relation to the attitude of the northern representatives (Gold Coast, 1951: 15).

That for want of fair and adequate representation in the past we have suffered considerable setbacks in many matters which vitally affect our economic and social lives. We have never ceased to feel that with well over a quarter of the population of this country to our credit, we have a definite right to a good voice in the Government thereof. It is gratifying to feel today that we are going to have it [Applause]. For the national interest, we are willing to try out the sort of coalition that this Government is to be; but we must make it quite clear that whereas we are prepared to support strongly every scheme or every policy that contributes to the sound economic development of our land and the unobtrusive advancement of our people, we shall never associate ourselves with any such scheme or policy as we shall find detrimental to the interests of our people [Applause].

In such circumstances we shall have the right to adopt any attitude that we consider fitting and proper in the interests of our people…

The word “gate” as used in relation to succession to chiefly office in Ghana refers to the families that can accede to the same skin in Northern Ghana or a stool in the South. Traditional rulers in the former area sat on skins while those in the latter sat on stools during official occasions.

The concern for the lack of development in the Northern Territories and the impending independence of the Gold Coast gave birth to the Northern Peoples Party in spite of the fact that “we were not unaware of our handicaps, such as our inexperience in party politics, our limited educational background, the large illiterate population of the North and above all, lack of financial resources” (p. 47). The chiefs also often pointed out that if a man’s wives conceived at different times they cannot be coerced to give birth at the same time. So, most of them initially threw their weight behind the NPP in demanding a slower pace in the progress towards the attainment of political independence.

The memoirs have added to the existing knowledge. It is well known that the first 19 members from the Northern Territories in the Legislative Assembly were elected on a non-partisan basis by an Electoral College comprising the Northern Territories Council and representatives of the District Councils. So they regarded themselves as independent of any political party and the interest of the North and the whole country was their focus. Bawumia has revealed that even when the NPP became the second largest party in the Legislative Assembly and was the official opposition in 1954, they did not abandon their objective as a pressure group and did not seek to be an alternative government, although the Ghana Congress Party had been decimated and the only member in the Legislative Assembly was Dr. K.A.Busia, who became Prime Minister of Ghana in 1969.

C.K. Tedam, Member of the Council of State, recently claimed, on a Ghana Television (GTV) programme on the recollections of some elder statesmen and women on the struggle for independence, that it was Dr. J.B. Danquah and other people in opposition to Dr. Kwame Nkrumah who urged Northerners to form a political party as the South had been lost to the CPP. Tedam was not a founding member of the NPP. He had been nominated by the local supporters of the CPP to contest the 1954 legislative elections but the Central Executive Committee of the party selected another person.

Tedam felt insulted and stood as an independent. After winning overwhelmingly, he joined the NPP (Ladouceur 1979: 120) and this pronouncement has not been borne out by these memoirs.

Bawumia, a founding member of the NPP, states that some of the northern members of the Legislative Assembly decided to form a political party and then consulted N.A. Ollenu of the Congress Party, who had earlier successfully defended the claims of the Nayiri in the land dispute with the Sandemanaba. Some assistance was also requested from Ollenu. Bawumia declares categorically that “He supported our move and also bought a van for our new party” (p.48). Bawumia declined the chairmanship of the NPP in favour of S.D. Dombo, Duori Na, since the Nayiri was a very strong supporter of the Northern Peoples Party and he did not want the new political organisation to be seen as a Mamprusi party or labelled as “Nayiri’s Peoples Party” (p. 49).

Interesting information on inter-party relations and the plebiscite in the British Trust Territory of Togoland have been provided. Bawumia has also answered a nagging question among Northerners: Why did Dombo relinquish the leadership of the parliamentary opposition to Dr. Busia when the NPP was the second largest party in the legislature? The NPP had hoped that the National Liberation Movement (NLM), with its massive resources and apparent popular support in Ashanti, would win all the 21 seats in that region and many more in the South and form the government. So when the NLM suggested an alliance, the leaders of the NPP initially hesitated but accepted the idea, as it would be mutually beneficial. It was agreed that if the alliance materialised the NLM should provide a leader in the person of Dr. K.A. Busia with S.D. Dombo as the Deputy. In the 1956 general elections the CPP won 71 seats and the alliance 33 (NPP 15; NLM 13; and others 5). Nonetheless, the NPP kept its word. The opposition parties were ultimately compelled to amalgamate and form the United Party (UP) by the Avoidance of Discrimination Act which prohibited the formation of political parties on regional, ethnic and religious bases.

The ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) which formed the government of Ghana in 2000 should not be confused with the Northern Peoples Party which was a regional political organization before the attainment of political independence.

In discussing the aims and roles of the NTC and the NPP in the struggle for independence, Bawumia has highlighted the part he played but not to the total exclusion of others. Indeed, at some stage, there appeared to be very little difference between the two organisations as most of the NPP members in the national legislature were also members of the territorial council. As a result of the efforts of the NPP and the NTC substantial improvements were made to the living conditions of the people. Hospitals, clinics, roads, primary and secondary schools were built and scholarships were provided for Northerners to go for higher education overseas. The first northerners were also employed in the Gold Coast Civil Service in 1958. However, a railway to the North was not built because of disagreement among the northern Members of the Legislative Assembly.

Bawumia points out that “The Northern Peoples Party cannot claim all the credit for these achievements but the Party must be credited for spearheading the fight for a better deal for the North in the pre- and post-independence era” (p. 62). Collaboration between the NPP and the NTC succeeded in addressing the issues of underdevelopment which “militated against the unity and harmony between the Northern Territories and the people of Southern Ghana thereby making integration of the North and the South more meaningful” (p.63). The political and traditional leadership of the North at that time skillfully made President Nkrumah “to understand and appreciate the situation and problems of the North and co-operated in not only finding solutions but also provided a programme of continuity for the upliftment of the North from its predicament” (p.63). The stance of the Northern Territories, Ashanti and Trans-Volta/Togoland, led to the creation of Regional Assemblies at independence, to partly cater for local regional concerns.

Mumuni Bawumia was unanimously elected as the chairman of the Interim Regional Assembly of the Northern Region immediately after the attainment of independence. As Kwame Nkrumah was against decentralization, the Regional Assemblies dissolved themselves as the CPP had a majority in all of them. Bawumia regarded their dissolution as a sad end to a long, bitter and worthy struggle: “The North lost a golden opportunity in its attempt to catch up with Southern Ghana in all spheres of development in the country. The abolition of the Regional Assemblies was a set back to effective accelerated development of the Region” (p.130). It has to be pointed out that regional autonomy per se, cannot assure socio-economic development even with abundant natural resources in the absence of upright, dedicated and visionary leadership and a disciplined population.

When the formation of political parties on sectarian bases was banned by the government, Bawumia was against the NPP joining the other opposition parties to form the United Party and decided not to accept any office in the new party. His view was that, having achieved so much for the North with the co-operation of Dr. Nkrumah and his party, the only alternative was for the NPP “to join hands with the CPP and continue the fight for northern progress from within” (p.132). As the CPP had overwhelmingly won the District Council elections in the North and the Regional Assemblies had also been abolished, it appeared to Alhaji Bawumia that there was no way to fight for the North outside the ruling party. The Nayiri and other leading chiefs in Mamprugu agreed with his view and Bawumia crossed the carpet. Kwame Nkrumah had earlier told Bawumia to do so and he would be made a minister.

Bawumia toured all the northern constituencies to explain his position and advised his supporters to join the CPP. The Nayiri issued a statement calling on his chiefs and people to support Dr. Nkrumah and the CPP government. Other northern and southern MPs also crossed the carpet and at one stage the only vocal opposition members in parliament were B.F. Kusi from Ashanti and four others from what is now the Upper West Region: Abayifaa Karbo, S.D. Dombo, Jatoe Kaleo and B.K. Adama. The reactions to Bawumia’s defection and the intrigues against his appointment as a Minister are documented in some detail (pp. 133–135).

As Bawumia was denied the opportunity for higher education during the colonial era, he was irritated by the small numbers of Northerners gaining admission to the universities in Ghana. He assisted northern students financially and opened up avenues for them at the University of Cape Coast. After consulting Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, he submitted a proposal for the establishment of an Agricultural University, with a medical faculty, in northern Ghana to the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) in September 1963. He persisted in keeping the matter alive and has reproduced the memoranda verbatim. Several committees were set up to investigate the issue, culminating in the establishment of the University for Development Studies (UDS) at Tamale in 1992. The University started operating in September 1993, exactly thirty years after Bawumia first petitioned for a higher educational institution in the North.

This text is culled directly from https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC45987