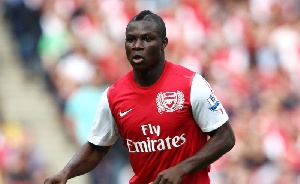

Frimpong announced his retirement last month at the age of 27

Frimpong announced his retirement last month at the age of 27

You honestly wouldn’t want to know.” Emmanuel Frimpong laughs when asked how, now that playing football is no longer an option, he spends his days. Life used to move at 100 miles an hour when Frimpong arrived on the scene at Arsenal, or at least it often seemed that way to those in his orbit, but things are different now. The hustle and distractions of London have been swapped for the mellower charms of Accra, capital city of Ghana. He describes an existence spent largely watching television while his two?year?old daughter, Emmanuella, is at playschool and, for someone who never had too much trouble courting attention, the appeal of settling into the background has been surprisingly seductive.

Frimpong announced his retirement last month at the age of 27 although he had decided to quit long before. In November 2017, he tore a knee ligament when playing for the Cypriot side Ermis Aradippou and had no appetite for further surgery on a joint that had already been operated on twice.

His return to the country of his birth last year came partly because he knew his time was up. “It got to the stage where I was playing through too much pain,” he says of the months before that final injury. “I just couldn’t put a pattern of games together. I’d be coming home and putting ice on my knee, my ankle, everywhere. It became hard to wake up in the morning and want to go to work.”

From parks to Premier League: the shocking scale of racism in English football Read more It has not diminished his enthusiasm for the sport. He watches Arsenal’s games and wonders whimsically whether fans of Unai Emery’s side might contribute £300 each to fund the defenders they need. The way Liverpool “fight, run, hassle and dig out results when they shouldn’t really be competing with City” also attracts him and he can speak from experience about another topic that pervades the headlines.

In July 2015, Frimpong claimed to hear racist abuse from a group of Spartak Moscow fans while playing for the Russian side, Ufa. He was sent off for responding with a middle finger and banned for two games; the Russian football union said it had found no evidence of any crowd misbehaviour and, in a parallel with Leonardo Bonucci’s lack of support for Moise Kean, the Ufa chief executive, Shamil Gazizov, advised Frimpong to “hold back the tears and put up with it”.

Advertisement

It shows, as if proof were needed, that neither situation happened by accident and he was not surprised to hear the exasperation Danny Rose voiced recently at the way football handles racism. “The point that all those at the top – Fifa, Uefa, whoever makes the decisions – are white men,” he says.

“I don’t blame them personally but how can somebody feel your pain if they’ve never been in that situation? Most of these people have never been racially abused; they don’t know what it feels like so any punishment they give comes from their world, not understanding the black person’s point of view.

“If things are to change then the committees need to be full of people with different backgrounds. How are they going to pass judgment on these people if they haven’t been on the other end? How would you feel if you came to Africa, full of black people, and were abused? You’d think: ‘My God, I need to get out of here’.

“Players don’t deserve to play the game they love and get abused for it, but in the end what’s changing? Nobody is doing anything. Countries can get fined €10,000 for racist chanting and it’s embarrassing.”

Sign up to The Recap, our weekly email of editors’ picks. Frimpong moved to London aged eight, growing up in Tottenham but joining Arsenal’s youth setup within a year. Racism was never a factor for him then and the topic surfaced only when, in unfortunate circumstances, he fired a broadside that almost certainly expedited his departure to Barnsley. His propensity to shoot from the hip via Twitter had already landed an FA fine when, in October 2013, he was angry after being left out of a League Cup tie against Chelsea. “Sometimes I wish I was white and English,” he typed through the red mist; it was quickly deleted but the damage had been done.

“When I was young it was my dream to play with Michael Essien, or just on the same pitch as him, and I was so disappointed not even to be in the squad,” he says. “Going back, it’s a tweet I wouldn’t have sent because, if you look at Arsène Wenger’s history, you can honestly say he has helped a lot of black players, perhaps more than any other manager. It was just a tweet out of anger and was not right; it was something I regret doing.

“You hold up your hand, admit what you did was wrong and move on.”

Frimpong has done that single-mindedly. It is a surprise to hear that he and Jack Wilshere, virtually inseparable as they came through the ranks, have hardly been in touch for years. There has been no fall-out; life has just changed in the decade since they were FA Youth Cup winners together and the only former teammate with whom he regularly communicates is Alex Song, who plays in Switzerland for Sion.

Similarly, his assertion that those days in Russia – he spent two years with Ufa and six months at Arsenal Tula – were the most enjoyable of his career comes out of the blue. He had made 16 appearances for Arsenal but, for a time in the 2011?12 season, seemed on course to succeed in a way that he says he had never considered during those academy days.

Emmanuel Frimpong in action for the Russian side Ufa where he spent two years. Facebook Twitter Pinterest Emmanuel Frimpong in action for the Russian side Ufa where he spent two years. Photograph: Epsilon/Getty Images “You would love to go to war with Frimpong,” Wenger once said, and his first Premier League start, against Liverpool, brought 69 minutes of bravura followed by a red card that epitomised his frayed edges. He never quite regained that dynamism after rupturing his cruciate ligament, his second such injury, during a loan spell at Wolves later in that campaign.

Any player who walks off over racism deserves all of football’s support Barney Ronay Barney Ronay Read more “Russia was amazing,” he says. “The perception was so different to the reality. I could do things and nobody would take them out of proportion, so I could really express myself. I feel everything’s so serious in England. Even the post-match interviews: they’re so boring. Players don’t say what they’re really feeling because they think people are going to judge them. That’s one of the things wrong in football: the game should be about telling the truth and expressing your emotions.”

He feels “that was a problem” early in his career and perhaps it was exacerbated by the fact he offered so much of himself. At Arsenal’s training ground his boisterousness could fill a room. Away from football Frimpong became synonymous with the catchphrase “Dench” and for his collaborations, in music and a line of clothing, with his close friend Lethal Bizzle.

As far as he was concerned there was no harm in pursuing other hobbies provided he had trained hard earlier in the day but, in a world of harsh social media judgment, it was clear not everybody saw things that way.

“I was raised to be respectful to my elders and everyone else, but at the same time I was raised not to take my life too seriously and to have fun,” he says. “I don’t think I was disrespectful to anybody during my time in England. I was just a young kid that was enjoying the game, enjoying my life. I’m just a human being like anybody else. You learn from your experiences, grow up and become a better person.”

The Frimpong of 2019 fears those days on the sofa are making him gain weight and would like, eventually, to work in football again. He is interested in the media and believes he could offer a fresh voice; he is reluctant, though, to seek help from old contacts for fear of imposing. For now he is happy with his lot and offers no frustration at the ill luck that meant his star burned so briefly.

“Nothing stays forever in life; it was just a privilege to do all those things,” he says. “That’s how it goes: you have moments, and you just have to enjoy them when they come.”