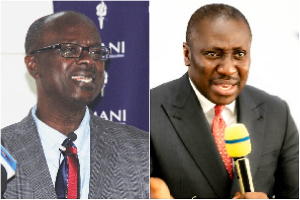

Prof Stephen Kwaku Asare (Kwaku Azar) and Majority Leader Alexander Kwamina Afenyo-Markin

Prof Stephen Kwaku Asare (Kwaku Azar) and Majority Leader Alexander Kwamina Afenyo-Markin

US-based Ghanaian lawyer and scholar, Prof Stephen Kwaku Asare has reacted to the injunction filed by the Majority Leader, Alexander Kwamina Afenyo-Markin, to declare four seats in Parliament vacant, which would change the composition of the House with regards to which party forms the Majority and Minority Caucus.

In a write-up shared on Facebook on Tuesday, October 15, 2024, the legal luminary, who is widely known as Kwaku Azar, pointed out that the injunction filed by Afenyo-Markin cannot stop the Speaker of Parliament, Alban Bagbin, from declaring the seats in question vacant.

He explained that Parliament, as the legislative arm of government, is independent and, per the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, can perform its function without any interference from either the executive or the judiciary.

He also cited a precedence where a court ruled that injunctions cannot stop institutions from performing their duties.

“The mere filing of an injunction against Parliament does not and should not stop parliamentary work due to the principle of separation of powers. Parliament, as a legislative body, is independent and has its own constitutional mandate to create laws and oversee the executive.

“This principle is not novel. In Republic v. High Court; Ex Parte Perkoh II [2001-2002] 2 GLR 460, the Court stated clearly that ‘the mere filing of an application for an interim injunction seeking to restrain a chief from performing the functions of a chief would not operate to restrain him from performing the functions of his office when he had not been destooled and the court had not so ordered.’ This ruling affirms that an application for an interim injunction, without a final order, does not halt the performance of official duties,” he wrote.

The academic also explained that injunctions are meant for persons involved in civil litigation to stop them from engaging in activities that would affect the case, and not state institutions.

“Admittedly, courts have held that ‘any conduct which tends to bring the authority and administration of the law into disrespect or to interfere with any pending litigation is contempt of court.’ As the court noted in Republic v. Moffat and Others; Ex Parte Allotey [1971] 2 GLR 391-40, once a respondent becomes aware of a pending motion, any action likely to prejudice a fair hearing or interfere with the due administration of justice amounts to contempt of court.

“However, the Moffat holding typically applies to civilian respondents, particularly those aware of pending motions but who proceed to take actions affecting the subject matter of the litigation. Moffat was never intended to apply to public entities, such as universities, hospitals, or legislatures. The presumption of regularity, which assumes public officials perform their duties correctly and in good faith, applies to these bodies,” he added.

Background:

Majority Leader Afenyo-Markin disclosed on Tuesday that he has also applied for an injunction to stop the Speaker of Parliament, Alban Bagbin, from declaring some four parliamentary seats vacant.

According to the Majority Leader, his decision to seek the court’s intervention is informed by a memo sent to the Speaker by the Member of Parliament for Tamale South, Haruna Iddrisu, who had earlier announced the intent of his caucus to invoke Article 97 (g) and demand that the seats of three New Patriotic Party MPs and that of an MP from the National Democratic Congress caucus be declared vacant.

The move by Haruna Iddrisu comes after the MPs for Agona West and Suhum, who are members of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), filed their nominations to contest in the 2024 parliamentary election as independent candidates.

The independent MP for Fomena has also filed his nomination to contest in the election on the ticket of the NPP, and the Amenfi Central MP, a member of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), also filed his nomination to contest as an independent candidate.

Article 97 [1(g) & (h)] of the 1992 Constitution states that “a member of Parliament shall vacate his seat in Parliament if he leaves the party of which he was a member at the time of his election to Parliament to join another party or seeks to remain in Parliament as an independent member; or if he was elected a member of Parliament as an independent candidate and joins a political party.”

See Azar’s full write-up plus a video from Parliament on the declaration below:

The mere filing of an injunction against parliament does not and should not stop parliamentary work due to the principle of separation of powers. Parliament, as a legislative body, is independent and has its own constitutional mandate to create laws and oversee the executive. This principle is not novel. In Republic v. High Court; Ex Parte Perkoh II [2001-2002] 2 GLR 460, the Court stated clearly that “the mere filing of an application for an interim injunction seeking to restrain a chief from performing the functions of a chief would not operate to restrain him from performing the functions of his office when he had not been destooled and the court had not so ordered.” This ruling affirms that an application for an interim injunction, without a final order, does not halt the performance of official duties.

Admittedly, courts have held that “any conduct which tends to bring the authority and administration of the law into disrespect or to interfere with any pending litigation is contempt of court.” As the court noted in Republic v. Moffat and Others; Ex Parte Allotey [1971] 2 GLR 391-40, once a respondent becomes aware of a pending motion, any action likely to prejudice a fair hearing or interfere with the due administration of justice amounts to contempt of court. However, the Moffat holding typically applies to civilian respondents, particularly those aware of pending motions but who proceed to take actions affecting the subject matter of the litigation. Moffat was never intended to apply to public entities, such as universities, hospitals, or legislatures. The presumption of regularity, which assumes public officials perform their duties correctly and in good faith, applies to these bodies. For these public entities, the Ex Parte Perkoh holding generally applies.

The Ex Parte Perkoh ruling applies with even greater force to the operations of parliament, which is a coequal branch of government. Allowing an injunction application to halt parliamentary work could disrupt its mandate and lead to judicial interference in the legislative process. Courts have long held that they would not interfere with parliamentary proceedings, as doing so would violate the autonomy of the legislative branch. Courts recognize the need to maintain parliamentary privilege, protecting the legislative process from undue judicial interference.

Moreover, parliamentary activities often involve time-sensitive issues or matters of national importance. Any interruption could severely hinder governance and the effective functioning of the state. If individuals could stop parliamentary work simply by filing an injunction, it would create opportunities for abuse and delay. Anyone with a personal or political agenda could file repeated or frivolous injunctions to disrupt the legislative process, using the courts as a tool to frustrate or manipulate parliament’s activities. This could prevent the passage of laws, delay debates on crucial issues, or interfere with government oversight. Such a precedent could lead to a situation where critical legislative decisions are stalled indefinitely, hampering governance and national development.

The constant threat of judicial intervention could weaken parliamentary efficiency, forcing parliament into an inefficient stop-start process, waiting for court rulings before proceeding. This would severely compromise parliament’s ability to fulfil its constitutional role, as articulated in the doctrine of parliamentary autonomy. Courts should be slow to issue injunctions against parliament because of the risk of undermining parliamentary independence and the principle of non-interference. The judiciary must respect parliament’s constitutional role and its freedom to conduct legislative business without undue interruption. Frequent injunctions could lead to judicial overreach, influencing legislative priorities or outcomes, thus breaching the separation of powers.

In Tuffuor v. Attorney General [1980] GLR 637-667, Justice Sowah emphasized the importance of maintaining distinct roles between the branches of government to preserve constitutional balance. This judgment highlights the judiciary’s responsibility to exercise restraint when considering interventions in legislative matters. Courts should intervene only in exceptional cases where there is a clear legal basis, and the harm to constitutional rights or the public interest justifies such intervention. Even then, courts must carefully balance the protection of individual rights with the need to preserve parliament’s autonomy. Judicial restraint is crucial to ensure that the judiciary does not become an instrument of delay or political influence over parliamentary operations.

#SALL is the cardinal sin of the 8th Parliament. Da Yie!

BAI/AE

Watch the latest episode of Election Desk below

Ghana’s leading digital news platform, GhanaWeb, in conjunction with the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, is embarking on an aggressive campaign which is geared towards ensuring that parliament passes comprehensive legislation to guide organ harvesting, organ donation, and organ transplantation in the country.