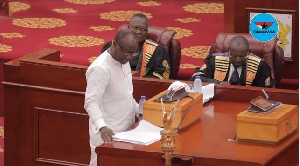

Finance Minister Ken Ofori Atta presenting the 2018 budget before the House on Wednesday

Finance Minister Ken Ofori Atta presenting the 2018 budget before the House on Wednesday

Ghana’s Finance Minister, Mr. Ken Ofori- Atta presented his second budget to Parliament on Wednesday, November 15, 2017. The 2018 budget broadly aims at stabilizing the macroeconomic fundamentals and growing the economy by investing in industrialization, infrastructure, agriculture and entrepreneurship to create jobs.

The general outlook of the 2018 Budget reveals Government’s commitment to fulfilling its numerous manifesto promises made in the run-up to election 2016 while striving for fiscal discipline.

Imani’s preliminary budget analysis examines the key policies, programmes and how allocations to the various projects will affect key sectors of the economy. Critical questions were asked as well as policy recommendations to fill the gaps identified.

Economy

Ghana’s economy has achieved relative stability and appears to be on a trajectory to recovery after the numerous challenges, it experienced in the past few years. The much talked about debt reprofiling seems to be yielding some positive results as debt to GDP ratio has improved from 73 percent in December 2016, to 68.3 percent as at September 2017. GDP Growth outlook for 2017 is also set to exceed its target by about 160 basis points. At the same time, fiscal deficit is within range of the target even in the face of revenue shortfalls – a fiscal deficit of 4.6 percent of GDP has been projected for 2017 against a target of 4.8 percent of GDP.

A careful analysis of the revenue performance and the expenditure management for 2017 reveals an impetus to ensure fiscal discipline. In the thick of revenue mobilisation challenges, the incumbent government has spent below estimated expenditure levels. This action undeniably contributed to keeping Ghana’s debt below unsustainable levels (70 percent of GDP).

All the above has contributed to the positive ratings Ghana enjoyed in the recent Standard and Poor’s outlook review of the Ghanaian economy. The positive rating will augur well for the economy as it can attract investors to support both the industrialization drive and the infrastructure agenda of the government.

While meeting fiscal deficit targets has its advantages, constraining expenditure to achieve it presents challenges of its own. With a dominating wage bill and numerous social intervention programmes, expenditure cuts, unfortunately, mean reduction in growth catalyst items like capital expenditure.

In the 2017 budget, the wage bill, which is the highest component of expenditure, was 30.68 percent of total expenditure. In the face of revenue shortfalls, actual compensation expenditure was still above the allocated amount by about 2.64 percent. Interest payments, the next biggest item was about 25.4 percent of total expenditure with grants[1] to other government units following with 18 percent, which increased to 20 percent (in the revised budget) even in light of expenditure cuts.

Capital Expenditure (CAPEX), which followed with 13.6 percent was later revised to 12.35 percent. However, the government is projecting to spend only 8.8 percent (29 percent less than intended) in view of the expenditure cuts. In the 2018 budget, CAPEX is expected to be 11.25 percent of total expenditure with compensations at 32 percent and grants to other governmental units at 19.7 percent.

Government in addition to intensifying its revenue mobilisation efforts must consider finding efficient and innovative ways to include the private sector in the provision of these social programmes. Also, the proposed revenue measures such as the intended reform of the customs warehousing regime and transit regime, if carried out efficiently and timely, can potentially improve revenue mobilisation.

Inflation has also been on the decline since September 2016 – it has fallen from 17.2 percent to 11.6 percent as at October 2017, on the back of stable electricity supply and a relatively stable Ghana cedi (the Ghana cedi depreciated by 4.42 percent as at September 2017 against a depreciation of 9.6 percent in 2016 against the US dollar).

As part of projections for next year, the government has projected an average inflation rate of 9.8 percent and end-year inflation of 8.9 percent for 2018. While achieving this target can encourage savings and investments as returns on investments are preserved, provision of a stable and reliable electricity supply, delivery on its promise to reduce electricity tariffs, the significance of the reduction in terms of its impact on cost of production and continuous stability of the Ghana cedi will be imperative. A strong US dollar could also challenge the stability of the Ghana Cedi which can affect the achievements of the set inflation targets. It is recommended that government consolidate its efforts to provide more stable and reliable power supply.

Government must also increase efforts to improve the consumption of locally manufactured products. In this regard, the government’s decision to allocate 70 percent of all government contracts to local contractors and suppliers though commendable, will require strict enforcement to achieve intended results.

Interest rate

In a high-interest rate environment, such as Ghana has been experiencing, a reduction in interest rate is critical to driving investments in order to generate growth and to create essential jobs. Between 2016 and 2017, the Monetary Policy Rate, the 91 day Treasury bill rates and interbank rates saw significant reductions. While the MPR fell 450 basis points to 21 percent, the 91-day treasury bill rate fell from 16.8 percent to 13.2 percent. Average lending rate, however, remains high even though it fell marginally from 31.38 percent to 28.96 percent.

Meanwhile, with key challenges to credit such as limited information persisting, credit to the private sector grew by just 3.2 percent (as at September) in 2017 as against 17.4 percent (as at September) in 2016.

According to the recent World Bank Doing Business index, credit bureau coverage in Ghana is only 16.5 percent of the adult population with a zero percent credit registry coverage. While the 2018 budget has indicated the launch of a national development bank and intentions to expand the capacity of the EXIM bank to support agriculture and industrialization, there is no mention of policies to address the limited credit information challenges faced by banks in the lending business, especially those lending to Small and Medium Enterprises.

It is recommended that the government, in consultation and collaboration with the private sector, find reliable and sustainable means of generating and distributing credit information (both positive and negative). This will ensure increased and sustainable credit flows to the private sector and also attract investments into the banking space.

Job creation

Unemployment continues to be a major challenge in the country despite numerous promises and policies to create jobs for the youth. The government for instance in the 2017 budget projected about 750,000 jobs would be created under the Planting for Food and Jobs programme.

The 2018 budget, however, provided no details on the number of jobs that have been created so far under this programme.

In the 2018 budget, several policies and programmes have been outlined to create new jobs for the youth in various sectors. To deal with the increasing graduate employment challenge, the government has allocated GHs 600 million to employ 100,000 graduates as part of the Nation Builders Corps programme (NabCorp). Successful recruits will be trained and engaged in various sectors of the economy, ranging from health, education, revenue mobilisation etc.

This programme is a reflection of policy incoherence and a myopic approach to solving graduate unemployment challenge. The focus of the 2018 budget is to revamp agriculture for food sustainability and feeding the numerous factories to be established under the 1-district-1-factory policy. Interestingly, the amount allocated to the Ministry of Agriculture, which is annually inadequate, was cut by 21 percent. The decrease is likely to affect productivity outcomes in the sector.

However, the elephant in the room is the ageing cocoa and food crop farmers and the low interest of the youth to venture into agriculture. One would have thought a policy to engage graduates across the country would centre on finding innovative solutions to encourage graduates into agriculture.

A more prudent solution to graduate unemployment would be to invest the 600 million cedis allocated to the NabCorp into providing financing through a seed fund to encourage more graduates into the value chain of agriculture. The existing financing options for the youth interested in agriculture are unfavourable, expensive and limited.

Existing programmes such as planting for food and jobs targets mainly existing farmers and does not make available direct access to funds for agro-based start-ups. Other training programmes targeting the youth at the district levels do not come with grants. Seed funding for graduate agribusinesses will, therefore, be a better option to create immediate jobs across the country, which can be scaled up over time with financing from traditional financial institutions.

Also, creation of the establishment of NabCorp is an affront to the NEIP policy that aims at creating an entrepreneurial nation. The biggest challenge graduates face in starting businesses after their national services is access to “cheap funds” and business development to pilot their ideas or project research after school. However, only 50 million cedis has been allocated to NEIP as initial funding to support 500 youth businesses in 2018. The allocation to the nebulous NabCorp, when channelled to NEIP to create a special venture capital for graduate startups/projects, would create more sustainable jobs in the medium term.

Though the details of how the NabCorp programme will be operationalized has not been stated, it is difficult to differentiate between it and the compulsory one-year national service every graduate in the country has to undertake. The National Service programme already provides hands-on training and apprenticeship to graduates and transitions them well into the world of work after school as they serve their nation in various sectors. What additional skills will the NabCorp offer graduates who have been trained for four years in specialized fields?

What graduates in Ghana need are sustainable jobs created by a thriving private sector, entrepreneurial training and seed capital to start their own business.

Agriculture

The 2018 budget demonstrates government effort to transform the economy via the agriculture sector. Numerous projects and programmes have been outlined aimed at addressing the persisting challenges in the sector; access to finance, low mechanisation,post-harvest losses, low technology uptake, etc. For instance, about GHS 100 million has been allocated towards the implementation of the Ghana Incentive-Based Risk Sharing System for Agricultural Lending (GIRSAL), a Bank of Ghana initiative aimed at incentivising banks to give credit facility to the agriculture sector.

There is also a decision to purchase various types of machinery, rehabilitate dams and support livestock and poultry farmers. The budgetary allocation to the Planting for Food and Jobs programme has been increased from a GHS 560.5 million to GHS 700 million. These aforementioned programmes look good on paper and have the potential to boost the agriculture. The onus, however, lies on the government to effectively implement them

Tourism

The 2018 Budget highlights the government’s commitment to improving tourism infrastructure, as well as the promotion and marketing of tourism. The 2017’s budget reduction in capital expenditure by approximately 74 percent was concerning because such resources were necessary to ensure the ongoing development of tourism infrastructure in tourist sites such as proper sanitation, signage, and good roads.

While the government leaned towards working alongside PPPs to achieve this, public investment still plays an important component, if not greater role. The 2018 budget still maintains PPPs to facilitate the infrastructure drive, for example, in developing standards for new tourism enterprises. However, the increase in CAPEX, which marks an increase of about 1,577 percent from the 2017 budget (From GHS 1 million in 2017 to GHS 16.7 million in 2018), reflects the government’s realisation that increased spending in tourism has great potential to drive economic growth, and that its own investment and development in the sector is consequently, very important. Going forward, it recommended that government continually seek private partnerships to invest in good roads and other infrastructure that will attract the needed private sector investment. Government should also provide incentives to private businesses who will, for instance, want to invest in the ecotourism and historical sites.

Energy

Energy Bond, Cash Waterfall Mechanism (CWM) and Electricity Tariff reductions

Proceeds from the Energy Sector Levy (ESL) increased from GHS 1.6 billion in 2016 to GHS 1.9 billion in 2017 (projected revenue by year-end 2017) and is expected to reach GHS 2.1 billion in 2018. Efforts on the part of government to reduce the energy sector debt have been laudable considering that the debt has been reduced to GHS 5 billion from GHS 10 billion via payments made through the Energy Sector Levy (ESL) as well as via the proceeds of the energy bond (proceeds were, however, unspecified in the budget).

However, the energy bond-cash waterfall mechanism-electricity tariff reduction combination of policy initiatives is an intricate one which needs to be carefully handled or else gains from debt reduction will be quickly eroded.

The Cash Waterfall Mechanism (CWM) which focuses on “allocating and paying collected revenues to all utility service providers and fuel providers”[1], prima facie, does not immediately deal with all the factors that led to the accumulation of debt including excess generation capacity, technical and commercial losses of the distribution utility, government non-payment of utility bills as well as inadequate diversified sources of fuel supply for growing thermal generation.

As long as these factors exist, the CWM approach may not yield desired results and the likelihood of further debt accumulation remains.

Careful consideration must also be given to the impetus towards reduction in electricity tariffs in light of the above.

Though government’s move to reduce electricity sector tariffs on the surface, looking at only short to medium term gains has the appeal of reducing the tariff burden of consumers, there is the potential of jeopardizing debt restructuring efforts through the ESLA and energy bonds. Insofar as the energy sector levy is built into the electricity tariffs, if tariff reductions will affect the Energy Debt Recovery Levy, the Public Lighting Levy and the National Electrification Scheme Levy, then the electricity tariff reduction strategy may potentially upset debt restructuring efforts. Further, the tariff reduction strategy must not circumvent automatic tariff adjustment which is a key pivot of the debt restructuring effort.

If the factors that led to debt accumulation are not dealt with thus further debt is accumulated, and enough revenue is not raised to support the operation of the CWM given the persistence of the debt accumulation factors as well as reduction in electricity tariffs, debt restructuring gains will be eroded and the government will be issuing bonds for a long time.

Ministry of Special Development and Initiatives

The allocation of GHS 423 million to the Ministry of Special Development Initiatives towards capital expenditure (capex) for the Infrastructure for Poverty Eradication Program (IPEP) from the Road, Rail and Other Critical Infrastructure Development priority area of the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) is a bit worrying; especially considering the fact that only GHS 150 million (a reduction from the 2017 budget allocation of GHS 177.8 million) was allocated to capex for rail infrastructure and GHS 200 million to capex for road infrastructure.

Earlier caution had been given in our analysis of the 2017 budget concerning the vagueness of the “Other critical infrastructure” aspect of the priority area because it gives room for the thin spread of the ABFA. There is no comprehensive policy document that details the projects the IPEP would cover (even though some of government’s flagship projects have been listed) yet the programme has been allocated GHS 423 million. It will be useful for the government to clearly justify this allocation by presenting the details of the programme that warrants this allocation.

National LPG Cylinder Recirculation Policy

The government’s move to push forward with the LPG cylinder recirculation model is commendable. In rolling out the policy next year however, the government has to be mindful of the fact that gas explosions still remain largely a function of safety measures than location of gas filling stations.

Therefore gains from the recirculation model risk being eroded if critical steps are not taken to strictly enforce safety measures at the bottling plants to be established. Further, there is the need to harmonize the work of all relevant oversight bodies including the National Petroleum Authority, the Ministry of Planning (Town and Country Planning) and the Ghana Standards Authority and to ensure proper monitoring and supervision in the performance of their roles.

This is to both ensure that safety measures are upheld and that communities do not develop around bottling plants. The business model for rolling out this policy must be robust to ensure sustainability of the policy over time and also to rope in the existing 307 Bulk Road Vehicle operators and 647 gas filling stations. It is also necessary to reconsider and fast-track the recapitalization of the Ghana Cylinder Manufacturing company which has been unduly delayed. This will ensure the security of supply of LPG cylinders as well as serve to reduce imports of cylinders.

Finally, it is important to segregate the market into industrial, commercial and residential segments in order to adequately meet the needs of these segments while avoiding LPG shortage and the development of a black market.

Rooftop Solar for MDA’s

The move of government towards rooftop solar for MDA’s may be considered laudable. But if Energy Commission’s rooftop solar program is anything to go by, the government’s target of 2-3 percent increase in renewable energy generation will not be achieved. The target of the Energy Commission’s rooftop solar program when launched in 2016 was to achieve 200,000 installations within 1 year. As at the end of 2016, only 89 full installations had been completed across the country. This is chiefly because, while the solar panels are provided for free by the commission to citizens who sign onto the programme, the balance of systems (solar batteries, charge controllers, inverters etc.) to be purchased by the citizens to make up a full installation remain prohibitively expensive considering the power requirements of an average middle income household or a commercial enterprise.

To make adoption of rooftop solar by MDAs viable the approach should be a bottom-up one which will include reorienting the way energy is used within the public sector. For instance; most MDA offices use large power consuming appliances such as air conditioners, kettles, microwaves, fridges among others. It will be highly expensive if these appliances are to be powered using solar. There is a critical need to enforce strict energy efficiency rules at such premises.

[1] Budget Statement 2018

Education

Ghana’s education sector experienced a provisional growth of 9.1 percent and was the second highest performing sub-sector in terms of growth in the service sector in 2017. Over the period, the number of the beneficiaries of the ‘destiny changing’ Free SHS policy were 353,053 first-year students made up of 113,622 Day students and 239,431 Boarding students.

Total enrolment at the basic level increased from 7,736,145 to 7,778,842 representing a 0.55 percent increase. 49,000 teacher trainees from 41 public Colleges of Education benefited from the restored teacher trainee allowance and 86 percent overall progress on the construction of the 23 new Senior High Schools was achieved.

In general, the total budget for the Ministry of Education, including the GETFUND, saw an increase of 11.6 percent in 2017, when the budget was GHS 9.12 billion, whilst in 2018 the designated spending was GHS 10.18 billion. The amount allocated to employee compensation also increased by 11.5 percent from GHS 6.5 billion in 2017 to GHS 7.2 billion in 2018.

Goods and Services increased by 0.04 percent from GHS 1.35 billion in 2017 to GHS 1.36 billion in 2018. A critical look at the policies and programmes provides an indication of the government’s commitment to making education accessible and ensuring participation by all. A review of the capitation grant from GHS 9 to GHS 10 for 6.37 million pupils, an absorption of BECE registration fees for all public-school candidates and supply of textbooks are a few of the programmes.

The capitation grant increase is welcomed, as 75 percent of households surveyed by NDPC said they paid some levies or fees at the basic level of education[2] and it affected the access to education for their wards. Therefore, the plight of parents and school heads has been lessened given their calls for an increase in the capitation grant.

The proposed establishment of the Voluntary Education Fund to support education is a good initiative in the education sector. However, it raises more questions about the sustainable funding of education policies like Free SHS policy and Teacher Trainee Allowance. The budget allocated an amount of GHS 1.34 billion for the implementation of the Free SHS policy in 2018 through the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) and the Government of Ghana fund (GoG) and skewed towards Goods and Services. Implementation challenges of the free SHS, specifically with infrastructure and the poor revenue performance, have been revealed recently.

It has become imperative for the government to find innovative ways of funding the free SHS policy, especially the inadequate infrastructure, which is well documented. CAPEX allocation in the education budget is GHS 671 million, accounting for 6.6 percent of the total education allocation and mainly funded by Internally Generated Funds (IGFs) and Development Partner Funds (DP). This is not encouraging as Infrastructure is vital in the achievement of the quality education enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goal (4) and the African Union agenda 2063. The question which needs answering is what will be the setup of the voluntary education fund if established?

While the progress under education is commendable, according to the “Country Private Sector Diagnostic’’ study by the World Bank Group, the education sector provides a high growth potential of multiplier effect on the economy if the role of the private sector is encouraged. Granting of tax relief to privately-owned universities and, in the near future, for privately-owned SHS is encouraging and should be sustained to help build the human capital that the country needs in light of the industrialisation drive being pursued.

Health

From 2017 to 2018, the budget allocated to the Ministry of Health marginally increased from GHS 4.23 billion to GHS 4.42 billion. This translates to a 4.64 percent increment year-on-year. This increase reflects the government’s intentions over the next year to increase the number of healthcare professionals by 15,000, to increase the coverage of vaccines and antiretroviral drugs distributed throughout the country, and to continue construction of health infrastructure. From 2017 to 2018, all budget allocation sources and items, except those coming from Development Partner Funds, and allocations to Goods and Services by the Government of Ghana (GoG), rose.

The aforementioned allocations decreased by 42.5 percent and 96.7 percent respectively. Although the budget included a provisional allocation of GHS 187 million for the provision of essential drugs as a priority programme, the effect of the decrease in the GoG allocation to Goods and Services by 96.7 percent is ambiguous given the government’s plans to increase the number of vaccinations and antiretroviral drugs in the next year.

Over the past year, the government paid half of the National Health Insurance Scheme’s total arrears of GHS 1.2 billion, owed to healthcare service providers. In the 2018 Budget Statement, the government also stated the intention to review the funding sources of the NHIS, presumably with the view of including more non-state alternative sources and ‘reviving’ the NHIS. In the past, the NHIS has been funded by the National Health Fund, which comes from a combination of SSNIT contributions and the National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL).

The active membership of the scheme grows every year, increasing the burden on the NHIS. Meanwhile, the allocation to the fund minutely increased by 4.6 percent from the GHS 1.7 billion allocation in 2017 to the GHS 1.8 billion allocation in 2018. Given that multiple studies over the years have pointed to the unsustainable nature of the current financing structure of the NHIS and the fact that the current government have also acknowledged this, the question arises of how exactly the NHIS will be funded in the future to ensure that it continues to fulfil its mandate.

In the spirit of contributing new ideas to reform the NHIS, IMANI recommends the following as captured in our earlier publication in the year:

Providing an enabling environment to leverage the presence of private health insurance companies, which would foster more competition and drive down prices;

Making it mandatory for companies to provide private health insurance for their employees, which would take part of the burden off the NHIS;

The State covering the health insurance of only the most vulnerable in society.

Additionally, the 2018 Budget stated that the government would be exploring the possibility of financially weaning off some agencies under the Ministry of Health. The recognition and the efforts being made by government to explore complementary means to state funding for social basket programmes is commendable. This is especially justified given some past instances of alleged misappropriation of funds by board members within some health agencies and hospitals.[3]

Infrastructure

Investment into infrastructure sectors of the economy such as railway, roads, information technology, sanitation, water and housing does not only boost the economy by improving the efficiency but also creates several jobs which is the key target of the 2018 budget.

The World Bank in a recent report estimated that to address Ghana’s huge infrastructure deficit, a sustained spending of at least $1.5bn per annum over the next decade is needed to plug the infrastructure gap that exists[i].

It is therefore surprising to note that the allocation to public infrastructure declined in the 2018 budget. The total allocation to infrastructure sector in 2018 is GHS 1.804 million, a 31 percent reduction from the 2017 amount of GHS 2.624 million. This brings into question the priority the government is giving to the sector. The reduction in allocation will affect the routine maintenance and upgrade works on roads, bridges, rail stocks, housing and dams in the country. The hardest hit subsector is transport, which had an 83 percent budget cut in relation to the 2017 allocation. However, the aviation sector had a 230 percent increase in allocation compared to the 2017 budget.

The table below illustrates the comparison between the 2017 and 2018 budget allocations to the sectors under infrastructure.

Source: 2018 Budget.

Public-private partnerships bill blues

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have been identified as one of the alternate options to raise the investments required in bridging the country’s infrastructure deficit. Several PPPs are being considered for various infrastructure projects stated in the budget especially in the railway sector. However, the lack of a PPP legal framework to facilitate private investment is major drawback.

A PPP framework provides a clear legal framework for developing, procuring, reviewing PPP projects. It also promotes local content in PPP projects, value for money and accountability. Given how important this piece of legislation is, why has it not received the same level of urgency as the special prosecutor's bill and others, which were passed into law in the last 10 months? The bill was drafted under the erstwhile administration. With the emphasis the 2018 budget places on job creation, government must make the passage of the PPP bill into law a priority in the first quarter of 2018 to create more jobs and promote efficiency.

Getting the trains back on track

Investment in railway infrastructure will not only create more jobs but also improve the movement of goods and people across the country.

Plans to construct city railways will greatly ease the stress & traffic burden of commuters in Accra and Kumasi. Other railway development plans highlighted in the 2018 budget; Western Railway Line (Takoradi- Kumasi), Eastern Railway Line (Accra-Kumasi), Central Railway (Kumasi – Paga) will greatly boost economic activities and ease doing business in the country and with our neighbouring countries.

The sector was allocated GHS 544 million in the 2018 budget, representing a 5 percent increase to the 2017 allocated amount. The major challenge with these ambitious infrastructure plans is attracting private capital to complete them. The ministry of railways development was carved from transport with the intention to focus more attention on revamping the sector to contribute to economic growth.

However, the restructuring of the railway sector has not be expedited. The proposal to separate the Ghana railways development authority into two institutions: one as a regulator and the other managing the infrastructure by reviewing the Railway Act, 2008 (Act 779) has not be done.

The most efficient model that will ensure sustained investment into rail infrastructure is when the management of the infrastructure is separated from the operation, with government focused on regulating the sector and not a player.